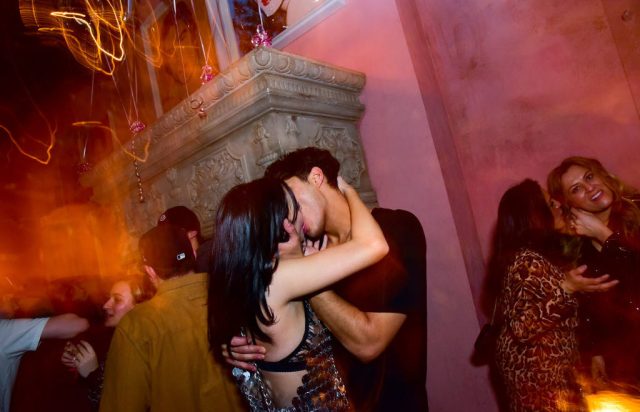

Hook-up culture has hollowed out our society. Credit: Sean Zanni/Getty Images for Rose Bar

A decade or so ago, while I was a dating columnist for thelondonpaper, I battled hard against the frequent assumption that I wrote about sex. I would insist to the confused — and particularly to those who slapped the label of ‘sex guru’ on me — that I wrote about the social aspects, the mores and manners of dating, not the bonking bit. But in the end people would always refer to it as a sex column. I suppose, after all, people do tend to bring everything back to sex.

That is the problem identified by Olivia Fane, author of a new, furiously anti-sex polemic, Why Sex Doesn’t Matter. Her rage — directed at the state and status of sex today, as well as at those who she blames for getting us here — is both deep and wide-ranging. While her targets constantly rotate and multiply, the overriding beef is this: we care too much about sex, and know too little about love, and this has corroded our moral and psychological relationship to the world.

Using Pride and Prejudice as a reference, she describes how Elizabeth Bennett and Darcy, who lived in “unsexualised times” would have “married in Church”, and “lived in utter devotion to one another and to God”. But we, in “the modern era”, have “successfully managed to turn everything inside out. We cheer the brute beast in us. We egg it on, the brute beast is the ‘inner me’.”

For Fane, this belief that sex is great and important, interesting and powerful, is the biggest mis-selling scandal of the 20th century. “Sex is neither moral or immoral,” she states, “it is a mere psychological drive which most of us have, and some more than others. Intellectually, it is utterly tedious and barren.” As she repeatedly asserts with reference to her dog Hector (to whom the book is dedicated), human sex is no different, really, from an animal humping a lamp-post.

However, humans are worse than dogs, because we pretend sex is something special. In so doing we turn our back on love, “the respect of another human being with the emphasis being on tenderness rather than desire”.

There is much that is incoherent and offputtingly reactionary about this book. But it also gets some things right. It is right, to start with, to say that sex is everywhere, and that the “dominant ideology of the day … that sex is important and profound and you are obliged to join in” can be oppressive, psychologically damaging and, ironically, bad for intimacy.

Indeed, what sensate Bumble dater hasn’t felt the deadening anti-eroticism and anti-romanticism of the dating landscape? Transactional casual sex is certainly attainable — a third of 25-34 year olds report having had a one night stand with someone they met online — but it often feels like the only kind of offer. Codes governing male-female interactions have been scrambled, replaced by nasty, cold new practices such as ghosting, benching, haunting and the slow fade, all designed to aid in treating sexual partners like ad-hoc service-providers. Technology is to blame for some of this, but the root cause of the rot is, as Fane identifies, an overemphasis on sex for sex’s sake.

There’s nothing new about this disgust with a modern sexual ideology that equates sex with self. In The Sexual Fix, published in 1982, Cambridge literary scholar Stephen Heath expressed a yowl of frustration not dissimilar to Fane’s. “I’ve suffered and suffer and I think others must too — it’s difficult not to in our society — from ‘sexuality’, the whole sexual fix. To the point of nausea,” he wrote.

Unlike Fane, Heath also offered a rigorous analysis of the cultural and sexual-scientific landscape. Modern sexology had regrettably made “sexuality [the] key to our being…the grounds for our judgement for ourselves, our lives, our worth”. The result, as obvious to Heath 37 years ago as it is to Fane now, was a miserable emptying-out and dumbing down of what it means to be human.

Attention to historical detail is handy when making arguments about sex and society — and would have helped Fane’s case a great deal. In particular, social history, the study of everyday life and experience, reminds us that prevailing ideologies are one thing, and how individuals navigate their private lives is another.

As the historians Kate Fisher and Simon Szreter found after interviewing people who got married in the 1920s and 1930s, new and ubiquitous external pressures to prioritise sex in marriage — trumpeted from women’s magazines, marriage experts and doctors — simply didn’t affect most interviewees, who barely mentioned orgasm or the drive for pleasure. Many saw “love as the primary purpose of sex”, indeed “the desire for orgasm was sometimes represented as a destabilising force in marital relations”.

One of the canards of Fane’s argument is that, where sex was concerned, the olden-days were ‘gentler’, wiser and more orderly, because thinking about male-female relationships was firmly rooted in edifying theology and men and women knew their roles. This is an idea that surfaces in much conservative thinking about gender and sexuality, usually to lambast feminism. But it is usually advanced without appreciation of the downsides. If sex in 19th century Britain looks orderly to us now, that is because it was policed heavily; the threat of public humiliation and private punishment was terrifying, as were the physical horrors of unwanted pregnancy or sexually transmitted disease.

It’s easy to rage at the shameless slathering over sexual pleasure of us moderns, but doing so without considering the fear and brutality used to enforce anything else is noxious. By all means call for a less sexually liberal society, but don’t forget that keeping sexuality in its box almost always involves violence.

Middle class parents in the 1930s, suspecting their children of masturbation, beat them. Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy, in his study of nannies, recorded the testimony of a retired female doctor who described the approach of an “indomitable Lancashire” nanny she had before WW1. The nanny believed that ‘“self abuse was the evil rotting the world” and, according to the doctor, “‘insisted on supervision in the lavatory, and put us to bed with our hands tied, sometimes too tightly. I remember my piano teacher commenting on my scarred wrists’”.

If, for girls in that ‘gentler era’, sex was polluted by the potential for punishment, shame and physical suffering, it was also an area of extreme ignorance. Information was not available, hard or perilous to find — and was often inaccurate.

We have gone too far in the other direction now, using sex education classes to promote ideological positions on matters such as consent and sexual identity, and normalising porn. Sex education organisations like Sexplain teach Year 8 “what LGQTIA+ means and why it’s important”; by Year 11 it’s “analysis of mainstream porn; framework of power”; “intersectionality and queer theory”.

But in those halcyon days of repression, long before any sex education at all, there was, as Fisher and Szreter found, a “pervasive culture of ignorance”. Knowing about sex, discussion or even mentioning sexual matters as late as the 1930s and 1940s was “lacking in respectability” and “verging on the immoral”. The result was that many women did not know that intercourse led to pregnancy; the belief that female genitalia were ‘dirty’ led to a dislike of one’s body, a reluctance to seek medical advice, maltreatment by doctors, and problems inserting tampons and diaphragms.

Most scholars agree that over the course of the 20th century, Western societies swung from a repressive, phobic obsession with sex, to the more narcissistic idea that sex is key for self-development and merits constant attention. But by focusing too narrowly on this narrative, one risks overlooking equally important developments.

The rise of the ‘companionate ideal’ of marriage, for instance, was championed with particular vigour by sociologists and politicians after the First World War. Generally, sex was not a central component of this ‘ideal’, which focused on mutual understanding and true friendship. Rooted in the traditional separation of gendered roles, where the man peacefully won the bread, and the woman ran the domestic sphere, it was very like the idyllic life Fane herself describes as the home-maker wife of a consultant surgeon. One can, therefore, look at the 20th century as the century in which love, not sex, got top billing.

Indeed, I’m often inclined to believe that it is in fact romantic love, not sex, that is the big mis-selling scandal of the 20th century. But in the end, trying to parse where love ends and sex begins is fruitless. The two can and very often do go hand in hand. Insisting they have nothing to do with each other makes for a spirited provocation, but is not convincing. Love matters, and so does sex.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe