Credit: Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

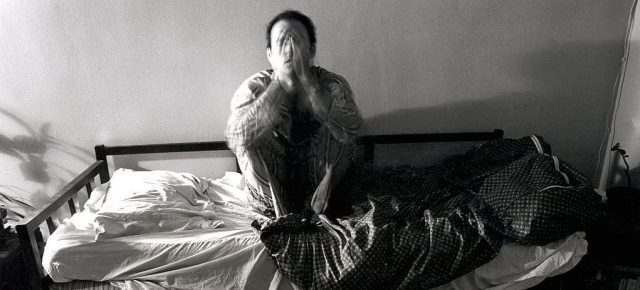

Claire Greaves was a young woman with anorexia and a personality disorder. She spoke candidly and courageously to broadcasters about her struggles; on her blog, she wrote about the abject misery of being stuck in a secure unit. She detailed the boredom, the distress, the loneliness and the violence after being stripped of all her possessions and rights.

She was not allowed clothes for months, and was forced to wear a humiliating anti-rip smock. At one point, she was prevented from obtaining sanitary pads. “I literally had blood running down the insides of my legs.”

Later, she talked in more hopeful terms about the start of her “recovery journey” after being moved to a Coventry hospital, although she worried that it was far from her home in Wales. Soon after arriving, another post detailed the horror of being restrained in seclusion, where she spent the best part of two days: “It’s scary, suffocating, closed in. Utter panic runs through my veins and frustration bubbles, boils and overflows,” she wrote. “I want to cry and scream and shout and kick and sometimes do. Overwhelming. Terrifying. Darker than dark. That’s what it feels like to be in there. Locked in.”

She accepted it was for her safety but concluded by saying: “Sad really to think that life has come to this.” Now those words feel even more poignant — for they were her last ones in public. Claire took her own life at that hospital, despite supposed one-to-one monitoring under her care plan.

An inquest last year reached an open verdict, after concluding that long-term use of seclusion and segregation had intensified the troubled 25-year-old’s mental decline; while staff levels, reduced observations and other care failings “probably caused or contributed” to her death.

This hospital was run by Cygnet, a fast-growing firm that is owned by the biggest healthcare operator in the United States. It insisted patient safety was “top priority” and claimed to have tightened procedures after Claire’s death. Yet the Care Quality Commission (CQC), the official watchdog that had raised concerns before the tragedy, later revealed a second death at the unit last year. On Christmas Eve, it threatened the hospital with closure, placing it in special measures and shutting down one “dirty, unhygienic” ward after inspectors found unacceptable levels of self-harm, staff shortages and routine use of restraint.

Now the CQC has gone further. It has, unusually, published an investigation report condemning the firm’s leadership for systemic failings rather than simply identifying units giving cause for concern. It criticised over-use of physical restraint and segregation, and highlighted more assaults and self-harm compared with services run by other providers. It also pointed out “active deception by hiding incidents and low staff numbers from the CQC and family members”, along with lack of strategy and safeguarding supervision. Statutory checks had not been made to ensure directors and board members met the “fit and proper” person test for their roles.

Once again the firm insists it is taking steps to improve its services and denies any complacency. It defends itself by saying it has “some of the most acute patients that other providers may not be able or willing to support”, effectively blaming patients for its own failures. “Would you ever hear people on a cancer ward described as ‘acute patients’ or having ‘complex needs’ as a cover for providing substandard services?” responded the Rightful Lives campaign.

Bear in mind this is the company that ran Whorlton Hall, the Durham hospital where 10 staff were arrested last May after an undercover BBC Panorama team exposed cruelty and abuse towards people with autism and learning disabilities. The 17-bed hospital was subsequently closed. Another seven Cygnet services were found to be ‘inadequate’ or threatened with closure by the CQC — more than any other private psychiatric care provider.

The firm was criticised also at an inquest last year into the strangling of a woman by a fellow patient that exposed staff failures. The jury concluded that if all the correct observations and procedures had taken place there was “possibility that death may have been prevented”. A nurse was dismissed after the killing for gross misconduct.

This is a catalogue of appalling failure. It should spark fierce debate over exactly what is going on behind the locked doors of secure psychiatric hospitals as rapacious private firms muscle in on the lucrative trade in locking up human beings. I have spoken to several patients and families who have told me of disturbing experiences inside Cygnet units during my year-long investigations into abusive detention of people with autism and learning disabilities. Latest figures show 2,190 such people remain incarcerated due to lack of support in the community, exposing shamefully-persistent political failure, despite endless pledges to end this scandal.

Like a small handful of other private operators, Cygnet has grown steadily amid an intensifying mental health crisis and thanks to increased state funding. It has taken over three rivals since August 2015, so now runs 113 facilities in England. Its most recent annual report boasted how it “did business’” with 228 NHS purchasing bodies, helping operating profits rise to £45 million in 2018. It almost doubled the remuneration package handed to its highest-paid director — most likely to be chief executive Tony Romero — from £508,000 to £953,000 while total spending on “emoluments” for directors surged from £912,000 to £2.4 million.

This is the ugly face of capitalism. There need to be far tighter controls on these fat cat firms. Matt Hancock, the health secretary, should stop mouthing platitudes and finally take action to end this cruel exploitation of vulnerable people. Even as I write this sentence, another email arrives from a despairing parent over her distressed daughter, stuck in segregation yet still able to swallow a latex glove. Strangely the Left, too, is largely silent on such profiteering from failure and misery. The unfortunate citizens stuck in cruel secure units where they are violently restrained, forcibly sedated and held in lonely isolation are second-class status.

Yet this issue does not just revolve around abysmal social care failures, nor even dismal private operators funded at great cost by taxpayers. (It can cost up to £730,000 a year per person in these secure units). For this latest CQC report raises a more profound question over our mental health system: why is our nation sending more and more of its citizens into secure psychiatric hospitals in the first place?

A few weeks ago I visited Trieste, which pioneered a very different approach to psychiatric care based on opening doors and embracing human rights. It dates back half a century to the actions of an iconoclastic psychiatrist named Franco Basaglia, who argued “freedom is therapeutic” as he unleashed 1,200 patients locked up in a huge asylum complex above the coastal city. His work — part-inspired by controversial ideas circulating in British psychiatry — led to an Italian law blocking admissions to public mental health units, which were replaced by beds in general hospitals and smaller community facilities. Five years ago, the country went further and phased out forensic mental health units.

His legacy in Trieste is impressive and moving. One British expert told me before I went that if he was suffering mental health problems, he would want to be treated in that city — and it was easy to see why. Teams of medics rely on discussion and persuasion, backed by local services open day and night, instead of chaotic institutions filled with stressed patients and overloaded staff. “We have open doors everywhere,” said Roberto Mezzina, who has just retired as director of the city’s mental health services.

“Our belief is anyone can live freely in the city with the right support. We have proved this over many years. There is nothing positive about coercion. There is no study showing it has worked anywhere in the world.”

The Trieste model is based on respect, treating patients with mental health struggles in the same way as if they had any other kind of sickness. Remarkably, this genial psychiatrist told me he had never used physical restraint in his 41-year career, relying instead on often-exhaustive negotiations with patients based on listening to concerns and understanding their anxieties. He joked about use of ‘gelato therapy’, taking stressed patients out for a walk, coffee or ice-cream to help calm them down.

Contrast this with our own country: the brutal techniques of restraint were used almost 100,000 times in English units in 2016/17, leaving more than 3,600 patients with injuries. Teenage girls have repeatedly told me of their terror at being held down by teams of adults, then forcibly injected with sedatives after being stripped.

It is naive to expect CQC inspectors to stamp out abuse in 22,949 adult social care settings, 234 independent mental health units and 55 NHS mental health trusts on their flying visits, even if the watchdog has belatedly gained a few teeth. But ponder a tale I was told by Mezzina in light of all the abuse exposed in our mental health system.

When he arrived as a young doctor in Trieste, he was tasked with helping to discharge the final batch of institutionalised patients, moving most back to live in the community. Their lives quickly improved as their rights were restored. Yet the impact on the nursing team was just as strong: they stopped abusing their charges after seeing their humanity. “I call this parallel empowerment — power should be bottom up and challenge everyone. You cannot change the system otherwise.”

Herein lies the key to what has gone wrong with our services. If you remove rights from people and detain them in secretive units, this can foster abuse — especially in a culture that looks down at people with autism, dementia, learning disabilities and mental illness. Yet we have seen rates of involuntary admission almost quadruple since the landmark 1983 Mental Health Act with a significant surge in recent years, which leads to increasing reliance on those private places run by multinational operators. Detentions rose another 2% last year alone. A debt-funded model relies on constant flow of fresh patients. Now more than half of mental health patients admitted are on compulsory basis — and almost four in 10 patients are then subjected to coercive measures such as restraint, sedation or segregation within four weeks of their enforced entry.

Politicians love to talk of ending the stigma of mental health problems. But our fear-ridden society views patients with such difficulties through a prism of danger. This demeaning attitude has been inflamed by reaction to high-profile murders by people with psychiatric problems, then intensified by funding shortfalls, slashed services and chronic shortage of beds. The result is that Britain, like some other countries, has ended up with a service that revolves around risk analysis rather than effective or more sympathetic treatment, with private firms soaking up gaps in services.

This approach is ethically and medically flawed. It is also fiscally foolish. Trieste’s open-door approach ended up costing only 39% of its old asylum, which needed more staff to guard patients round the clock. The most recent review of our mental health laws — sparked by a 40% rise in use of coercion over a decade — was scathing about people being detained for public protection when better and cheaper alternatives are available. Published 13 months ago, it highlighted the lack of respect for patients and how the environment in which many people are held “is now anything but therapeutic”. Many of those incarcerated people with autism and learning disabilities end up in a far worse state with severe post-traumatic stress.

These failings frequently prove fatal. A BBC investigation found unexpected deaths in mental health services rose 50% between 2012 and 2016, while I know of one hospital where 34 patients have died over the last nine years, highlighted by a father desperate to free his daughter.

Among the most appalling recent cases was that of Connor Sparrowhawk, a teenager with autism and epilepsy who drowned in his bath in 2013. Afterwards it emerged that the award-winning Southern Health trust had not even bothered to examine the deaths of some 1,000 patients with autism or learning disabilities, sparking a national review and showing once again the dismissive attitudes towards such people that plague our society.

We need far more than slogans to solve this health crisis, with an adult debate on everything from provision of decent, well-funded community services and rapid expansion of autism testing, especially for girls, through to candid discussion of the complex issue of euthanasia for suffering individuals seeking to end their own lives. But this discussion must be rooted in respect, not simply revolving around the detention of troubled citizens in secure units, out of sight from the wider public.

This is not simply an issue of privatisation, poor care and political failure. It is about power. And it is about the most fundamental of human rights — that of freedom from state oppression. Claire Greaves knew that she was severely ill, but wrote movingly on her blog of her dream to deal with her problems as an outpatient backed by a supportive mental health team. She wanted to work in a bakery, go to ballet classes and have a baby. It was her vision of “a life worth living” that she never managed to attain. So how many more must die before we see the real problem in our society?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe