What madness will this lead to? Photo: Paul Thompson/FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images

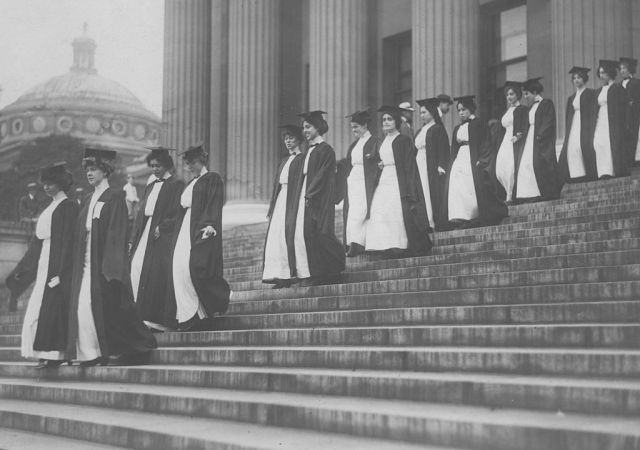

On 14 October 1920, the autumn sun pouring through the windows, the University of Oxford’s first women graduates were presented in the Sheldonian Theatre. As the south doors swung open to reveal the principals of the women’s colleges, resplendent in caps and gowns, the theatre — containing the largest-ever assembly congregated at the university — rang out in spontaneous applause.

That evening, the Somerville graduates — including the future novelists Dorothy L. Sayers, Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby — celebrated with a jubilant dinner, where a special toast was drunk to Emily Penrose, principal of the college, and where Professor Gilbert Murray presided as guest of honour. “I gnash my teeth when I think of all yr Somerville young women preening in cap & gown,” wrote Murray’s friend Jane Harrison from Cambridge, where proposals to admit women to full membership of the university — for which she had been petitioning since 1895 — were rejected that December for the second time. “So like Oxford & so low to start after us & get in first!”

A century has now passed since the first degree ceremony at Oxford — the University of London became the first institution in Britain to open degrees to women in 1878 — and across the world, girls’ access to education still remains a fraughtly contested issue, emblematic of wider questions around the freedoms afforded to women today.

The campaign for women’s education in Victorian Britain, wrote Vera Brittain, “represented the quintessence of the whole movement for women’s emancipation, the contest for the equal citizenship of the mind”. Across the latter half of the 19th century, activists had pressed for schools and universities to offer girls an education on equal terms with men, to secure the grounding necessary for employment and political influence.

“Why,” wrote Florence Nightingale in 1852, “have women passion, intellect, moral activity — these three — and a place in society where no one of the three can be exercised?” This proposed upheaval of the status quo stirred virulent opposition among commentators: some medical detractors argued that education would disrupt menstruation and cause dysfunction of the reproductive system; others feared that educated women would be introduced to sexual licentiousness through classical literature, that spinster teachers might peddle “oblique and distorted conceptions of love”, or that women’s widespread employment might presage an apocalyptic war between the sexes, culminating in the ultimate extinction of the race.

In 1873, two Oxford colleges offered a scholarship to the school student who obtained the highest results in the “Cambridge Locals”, only to withdraw the prize in embarrassment when that pupil’s name was revealed to be Annie Rogers. Rogers (who was awarded a set of books as a consolation prize) became the symbol of women’s fight for education, specifically in Oxford, where that year a series of “Lectures for Ladies” was established in borrowed buildings and attended by the daughters, sisters and wives of sympathetic dons.

Between 1879 and 1893, several women’s colleges were established as residential halls where pupils could live and devote their time to study. These often presented themselves more as homes than as educational establishments; the first principal of Lady Margaret Hall insisted to suspicious onlookers that far from setting in motion a societal revolution, “we want to turn out girls so that they will be capable of making homes happy”.

By the dawn of the 20th century, these colleges were tentatively established within the ancient university: women were allowed to sit all classes and examinations, though were not considered “full” students, nor was their work acknowledged with the award of a degree at the end. A female student recalled a don who began his classes “Gentlemen — and others who attend my lectures”, and another who insisted that the women sit behind him so he didn’t have to see them as he declaimed. Articles in the press constantly feigned concern that women were overworking, and that their minds and constitutions were not geared to such intensive toil.

But outside the university, women’s opportunities were fast expanding. During the First World War, women took over men’s jobs in the civil service, in munitions factories, in hospitals and shops; the war, wrote Millicent Fawcett, “revolutionised the industrial position of women — it found them serfs and left them free”. On 6 February 1918, women’s suffrage became part of the British Constitution, for property-owning women over 30; the following year, the Sex Disqualification Removal Act opened up many professions previously barred to women, stating that “a person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function”.

Back at Oxford, the campaign for women to be allowed to take degrees accrued new urgency. Rosamund Essex, who arrived there in 1919, recalled that “the women’s colleges were bursting at the seams, for the war had brought an emancipation for women which they could never have gained for themselves in so short a time. Besides that, girls knew now that most of them had to make their own way in the world and must be properly equipped for a professional life.”

Writing in the Oxford Magazine on 30 January 1920, Annie Rogers insisted that “Parliament has shown very clearly what it thinks about the removal of the customary legal disabilities of women,” and argued that the university should follow suit and not begrudge women credit for their labours. When the statute was debated on 17 February, women gathered with placards outside the Congregation House. On 7 October, the bill came into force, and Rogers herself graduated in the second ceremony to include females, on 26 October that year.

There remained dissenting factions within and outside the university: on 20 October, an editorial in the university’s Isis magazine expressed its fears that women “will outnumber and swamp the men”, who will be forced to retreat to Cambridge (which didn’t grant women degrees until 1948). Their fears remained unfounded for several decades yet: on 16 June 1927 it was reported that Oxford’s Council had voted to limit the number of women undergraduates to 620, maintaining a decorous ratio of one woman to four men.

Even by 1935, Dorothy L. Sayers could set her wonderful crime novel Gaudy Night in the serene setting of an Oxford women’s college, where the dons have dedicated themselves to their work at the expense of family life (making them exemplify, to detractors, a monstrous perversion of woman’s natural instincts). In a dark and premeditated attack on an institution of women’s education, sinister messages are daubed on the walls of the library or tucked into stray gowns.

As newspaper reports begin to hint at an apparent outbreak of insanity in a closed environment of educated single women, detective Harriet Vane sees at once that this scandal risks doing considerable damage to the ongoing fight for women’s education: “’Soured virginity’ — ‘unnatural life’ — ‘semi-demented spinsters’ — ‘starved appetites and suppressed impulses’ — ‘unwholesome atmosphere’ — she could think of whole sets of epithets, ready-minted for circulation.”

In her 1922 novel Jacob’s Room, Woolf describes a female student staring at the ceiling of the British Museum Reading Room while she waits for her books, noticing not a single woman among the names engraved on the dome. At the end of the decade, Woolf picked up similar themes and images in her essay A Room of One’s Own, delivered in 1928 as a lecture at Cambridge’s two women’s colleges.

As Woolf forcefully challenges women’s continued exclusion from intellectual life, she explores with sensitivity and nuance the ongoing struggle to establish conditions, material and emotional, under which artistic work can prosper. “Even when the path is nominally open,” she writes, “when there is nothing to prevent a woman from being a doctor, a lawyer, a civil servant —there are many phantoms and obstacles, as I believe, looming in her way.”

Today, we speak about “having it all”, perpetuating an unattainable ideal of achievement and fulfilment: still, women talk anxiously of how to reconcile their personal lives and careers, of the toll taken by refusing to conform to persistent narratives of how to live, echoing concerns little-changed from a century ago.

Yet Woolf’s words still resound, and we can still take up the gauntlet she threw down to her room of women students: “The room is your own, but it is still bare… How are you going to furnish it, how are you going to decorate it? With whom are you going to share it, and upon what terms? These, I think, are questions of the utmost importance and interest. For the first time in history you are able to ask them; for the first time you are able to decide for yourselves what the answers should be.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe