Credit: John Greim/LightRocket via Getty Images

A picture of a box from 1871 census form popped up on my Twitter timeline. It asks respondents to tick if there is a “lunatic” living in the house. Obviously, the word is now offensive. But I also find myself astonished by the simplistic certainty the question conveys: that there’s one simple thing called crazy, and you either are, or you aren’t.

My father is a psychoanalytic psychotherapist, so I grew up with the opposite world view: that we’re all a bit damaged, dysfunctional and deluded. On more than one occasion, when I expressed some teenage angst, he chuckled and — with great affection in his voice — said I was a fascinating bundle of psychopathology. When I accidentally stabbed myself in the hand with a pencil while revising for my A Levels, he described this as a “particularly primitive piece of acting out.” He was probably right.

Slowly, the world has come round to my father’s point of view. We have new shibboleths proclaimed by mental health advocates: mental health exists on a spectrum, just like physical health, they say. Sometimes we’re up, and sometimes we’re down. One in four of us is experiencing a diagnosable mental health problem at any one time: two thirds of us will experience mental illness in our lifetimes.

All this is technically true. But as a public narrative it’s creating its own disasters. If everyone is a little bit crazy, and everyone should ask for help, it creates a wall of demand that medicalised mental health services will never be able to meet, and that is compromising our ability to help those most in need. We are not in the middle of a mental illness epidemic. We are in the middle of a treatment crisis, where there is not enough help to go around.

Yes: about ‘one in four’ of us has a diagnosable mental health problem. But it was about one in four back in 1993 when we first asked this question in a survey of what’s called “Adult Psychiatric Morbidity”. It was one in four in 2000, in 2007 and in 2014. Of course, it’s absurd that this survey is only done once every seven years: we won’t have the next survey results until 2023 at the earliest, so maybe things have changed. But long term, the pattern is clear. Numbers of people with poor mental health are pretty stable.

So what’s changed? Why all the noise about a crisis? We’ve done something wonderful by stripping the stigma from mental health problems. We’ve empowered people to come forward and ask for help, instead of suffering in silence. Between 2007 and 2014 the number of people in treatment rose from 25% of those with symptoms of a common mental disorder to 40%. That’s an extra 1.5 million UK adults who felt able to ask for help, and got some.

So why am I not celebrating? Because providing treatment for those “common mental disorders” too often comes at the expense of help for those with less common, but more serious, conditions.

It’s vital to understand that there isn’t one single thing called “mental health problem” just as there was never a single thing called “lunatic”. Depression is not the same as bipolar disorder, which is not the same as anorexia, which is not the same as schizophrenia, which is not the same as post-traumatic stress disorder, which is not the same as post-natal depression, which is not even the same as post-natal psychosis.

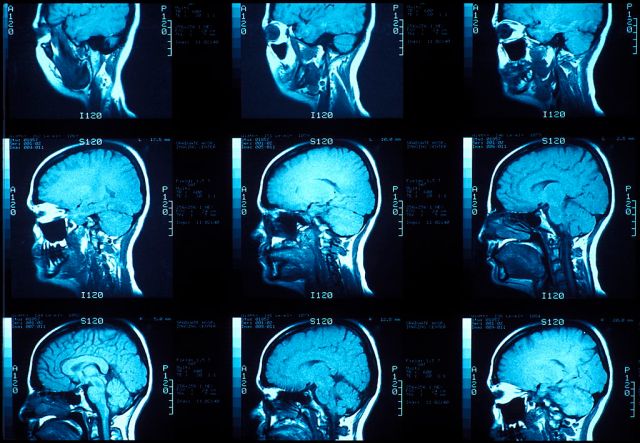

Diagnosis itself is, of course, controversial in mental health circles, and among people with these conditions or symptoms. We are largely swimming in the dark when it comes to understanding what is happening in the brain, or in what you might call the “mind”, if you believe such a thing exists separately from the squishy mass of neurons inside your skull. What we do know is that all of these conditions come with pain: pain so profound that it sucks the purpose from life and can lead people to isolation, rage, self-harm, and suicide.

The first job of our health services has to be to help those at most risk. The NHS often talks about people in crisis: that includes people considering ending their life, hurting themselves or someone else, and people experiencing psychosis — a break in their ability to comprehend reality that may include hallucinations or delusions. People going through a crisis of this sort need expensive care — either in-patient care in a psychiatric hospital, or intensive support in the community.

And you don’t need to be in crisis to need hospital care. People with eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, post-natal depression and a range of other conditions can also need intensive support for weeks or months at a time, to help them eat enough, care for their baby, or process their trauma. Doing that at home often just isn’t possible, and certainly not possible when you remember how little support is available. But we’ve all read stories of people denied help, or shipped to a hospital the other side of the country, because there just aren’t enough places to go around. We have fewer beds for this kind of treatment than we did in 1998.

That should be the story that dominates our headlines, not yet more celebrity interviews about challenging stigma that encourage everyone to put their hands up for help. I know celebrity depression is a lot more beautiful than a homeless man with schizophrenia who hasn’t washed since he lost his home because he thought the rent collector was a demon. But we mustn’t let the easy story crowd out the difficult one.

We have thrown extraordinary levels of political capital at stripping away stigma, and telling people it’s good to talk. There’s been an upsurge in the number of people getting treatment but no corresponding dip in the number of people with problems. This deluge of demand isn’t curing anyone, it’s overcrowding our stretched mental health services, and it acts as an epic distraction from providing intensive care for the 5% or so who are quite literally struggling to stay alive.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe