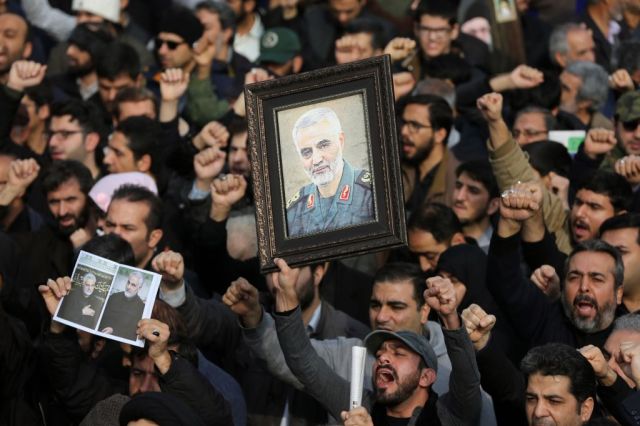

Mourners decry the killing of Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ Quds Force commander, Qasem Soleimani. (Photo by Fatemeh Bahrami/Anadolu Agency/ Getty

Things were going badly for Qasem Soleimani. The Iranian general’s goal of building a continuous block of Shia power from the Caspian to the Mediterranean Seas was being challenged by Iran’s most important ally and neighbour, Iraq. The protests that began in Baghdad at the beginning of October had changed the political dynamics, as the Arab Shia of Iraq rebelled against Persian domination.

The protests started over corruption, the uselessness of public services, the fact that there is no electricity for half the day and the water runs a sandy brown from the taps in Basra. There were no jobs in a country where 60% of the country is under 25. All this in the fifth largest oil producer in the world. The slogan was formed; “We want a country.” But, then, the protesters shifted their focus to sovereignty, as it became increasingly obvious that their politicians were not representing them and they were living in an occupied country.

Back in 2018, Qasem Soleimani, while denouncing Trump as a gambler and a barman, claimed Iran to be the nation of Imam Huseyn — the grandson of Mohamad, who was killed at Karbala by the wicked Calif Yazid in 680. But Iran is not the nation of Imam Huseyn. Iraq is. The Prophet Mohamad, and his family, whom the Shia revere, were obviously Arab. Karbala, where Imam Huseyn was killed, and Najaf, where Imam Ali, the Prophet’s son-in-law, is buried and the supreme Shia religious authority is based, are in Iraq.

Iraqis view the Iranians as newcomers, who don’t quite get it. Every year, around 15 million Iraqis — about half the country — walk to Karbala to pay their respects to Imam Huseyn. They are hosted and fed along the way in a pilgrimage known as the Arbaeen.

The protesters see themselves, and their nation, Iraq, as the embodiment of Huseyn; Soleimani and Iran, however, are deemed Yazid. In October, the protesters called a two-week break to go on the pilgrimage, and when they regrouped, the protests had grown to four times the size and spread to all the major Southern cities of Iraq. Tehran was confronting a sustained challenge to its domination and Soleimani had an insurrection on his hands. He had lost control of the Shia narrative. Since then, more than 600 protesters have been killed and 20,000 wounded.

As the demonstrations rolled on and the Iraqi prime minister, Adi Abdul-Mahdi, resigned, yet stayed in his job; and the president, Barham Salih, resigned, and yet carried on working as normal; and the government insisted it had given no orders to shoot, and yet protesters died daily, it became obvious that Tehran was ruling Baghdad.

“Iran Iran Out, Out, and Baghdad will be free!” was a chant I heard constantly when I was there for the Arbaeen. If the message of Imam Huseyn is that it is right to stand up to tyranny, corruption, hypocrisy and violence, then the problem for Soleimani was that the Shia of Iraq viewed the Iranian system of government as representing all those things.

By November, the protests had spread to Iran, where the internet was closed down for five days, during which time, at least 300 were killed and thousands imprisoned. The dead bodies were dumped, by night, outside their family homes. Soleimani was not, at that point, the embodiment of Shia ethics. On the contrary.

When I was in Baghdad, photos of Khamenei were being placed in the holes of the squatting toilets of Tahrir Square and the people gleefully shat into the hole of his mouth. When Iraq beat Iran in Qualifying for the Asian Championships, the Iraqi fans chanted, “Are you watching Soleimani?” The protesters beat his image with their shoes in town squares throughout the Shia south. They held him responsible for the hundreds of demonstrators who were killed, many shot in the head with tear gas canisters.

In Karbala, a holy city with a long and intense relationship with Iran, they torched the Iranian Consulate twice in one week. The protests were not going well for Iran and they were not going away. Each day the protesters sang of how they were willing to die for their country, and they did, and they kept coming back for more.

Soleimani took on a more public role. He was popping in and out of Baghdad regularly, brokering support for the government, propping up the prime minister, organising the militias, enforcing the crackdown. He chaired meetings of the security council in place of the prime minister. He was held responsible for the militia shootings of the protesters. He told the Iraqi government that, in Iran they had ways of “dealing with these things”. In Najaf, Ayatollah Sistani, head of the Religious Authority, supported the protesters, in opposition to Khamenei in Iran, and upheld a secular constitution for Iraq. The Iranian model was now being challenged by the people and clergy of Iraq.

In Baghdad, meanwhile, the protesters built a self-governing commune in Tahrir Square, they renovated and then slept in abandoned buildings, they repainted the road signs, the local population cooked them food. They built a cinema, established libraries and art exhibitions. Women took a leading role, with and without their headscarves. The Iraqi national anthem was played from rooftops on electric guitars and violins. The crowds were enormous and returned every night. They wanted a clean administration, the end of religious quotas and the militias. They called it a ‘normal country’. The rebellion of the Shia youth against Shia rule was unprecedented. Khamanei and Soleimani were daily defied and ridiculed.

But what had been forgotten by the protesters, as well as by the United States, was that Soleimani and Abu Mahdi Muhandis, deputy commander of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Units — a parallel army composed of various militias — who was also killed in the car with the general, had played a key part in the defeat of ISIS. In perhaps the dirtiest war since Stalingrad, they had fought their way through Anbar Province up to Mosul and forged a trust with each other and with the Iraqi people there who were grateful for their courage.

They were called heroes for a good reason. Soleimani and the Revolutionary Guards fought with the Iraqi Shia at the hour of their greatest peril. ISIS were unconscionably brutal and the PMU, with Iranian help and US air cover, fought them village by village, street by street. I was told terrible stories, when I was there, of beheadings, booby traps and child bombers. And yet they prevailed and ISIS was beaten.

The PMU was created by Ayatollah Sistani in 2014, when ISIS came within 10 miles of Baghdad, and he issued a Fatwa calling for action to protect the holy shrines. Millions of Iraqi Shia responded. It is these units, made up of poor Iraqis, that owe their allegiance to Solemeini. He led them in battle. These militias consider the demonstrators to be ungrateful — both to them and to Iran.

The Iranian Revolution, built around the rule of the Jurist, is now 40 years old with an established doctrine and followers. Their fundamental view is that only a strong Iran can save the Shia from oppression and all their history stands as testament to that. This mission of the Iranian State is only safe in the hands of the Shia clergy which has ultimate power. For them, this is an eternally true proposition. Khamenei is the expression of this, and in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen they have saved poor Shia communities from Sunni domination, which took on a demonic form with ISIS. The United States has proved itself to be reckless and fickle, at best. Trump’s unilateral abandonment of the Syrian Kurds to the mercy of Putin and Erdogan last October shocked a cynical region.

The United States under-estimated the loyalty of poor, non-urban Iraqis to the guidance and protection of the Iranian Revolution, and their militias, which persecute the middle-class but is faithful to the rural poor, and whose militias are of them. Qasem Soleimani was the boss of all that, the capo dei tutti capi of the Shia Militias, which he called the Axis of Resistance. His problem, though, was how to change the political dynamic in Iraq from the demonisation of Iran to that of the United States.

One of the fundamental rules of ‘Community Organising’, according to Saul Alinsky, is that “the action is in the reaction”. So, to change the dynamics of a situation, you pick a fight and then “personalise and polarise” around it. It’s what Trump did to “crooked Hilary”.

As the protesters in Iraq were polarising against Iran and Soleimani, they were the proximate source of domination. The attempts to shift that focus were getting nowhere. So Soleimani picked a real fight with the Americans, relying on the impetuosity of Donald Trump. Late last year, missiles were directed at an American airbase in Kirkuk, where ISIS are still active. These killed an American contractor. The US responded with a missile attack that killed a pro-Iranian militia leader.

On New Year’s Eve, the Iranian proxies responded with a re-enactment of the 1979 Teheran US embassy siege in Baghdad. They ransacked the building and sprayed pro-Soleimani and Khamenei slogans on its office walls. It had the desired effect. If there is one thing Trump knows, it is not to look like Jimmy Carter in election year. He was triggered and was trigger happy.

The final act of Qasem Soleimani was to succeed, through the sacrifice of his life, in polarising the Iraqi Shia against America, rather than Iran, and in consolidating support for the Iranian regime across Iraq. It was a sacrifice worth making. The young protesters are now isolated in their expression of anti-Iranian sentiment.

The Iraqis are now leading mass protests and mourning marches for Soleimani and Muhandis with their distinctive flags and rituals. Karbala and Najaf are no longer owned by the protesters but by the militias. And now, Muqtada Al-Sadr’s crew is burning down tents, fighting for control of Tahrir Square.

And behind them is something worse. Badr, Amiri, the Revolutionary Guard… Flags and songs are no real resistance to the bullets and knives wielded by these people born of violence and terror who know of no other way. The protesters had previously been shot with tear gas canisters, now live ammunition is used against those refusing to participate in the mock funeral of Muhandis held in Nasiriyah. They have real reason to be scared, for the Iraq government is now squarely aligned with the militias. Another triumph for Soleimani in his death. For the first time for three months, the crowds in Tahrir Square are meagre and the mood apprehensive.

The action is in the reaction. By polarising against America, Soleimani has also delivered a newly compliant government that will act against the US with renewed legitimacy and the Iraqi parliament has called for the removal of all American forces. The legacy of his death will be the expulsion of the American military from Iraq and a generalised threat to their presence across the region. In dying he has secured his ultimate goal and ensured that his reputation grows.

The antipathy to Iran is deeply held and long-standing in the Iraqi Shia. They do not want their system or to be ruled by them. This was finding an intelligent and sustained expression throughout the three months of the protests that were present each day in all the major cities of Shia Iraq. That momentum has now been halted by the sickening thud of a car accident.

The fundamental teaching of Imam Huseyn is that sacrifice is eternal. In dying at the hand of Yazid, a corrupt hypocritical tyrant, Imam Huseyn achieved immortality and the accolade of the ‘Prince of Martyrs’. That is now a status he shares with Qasem Soleimani.

But the real heroes were the protesters, the real martyrs those 600 or more young people who were killed on his orders. With one act, Trump has ceded victory to his enemy, glory to his foes and martyrdom to murderers. It is a remarkable achievement.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe