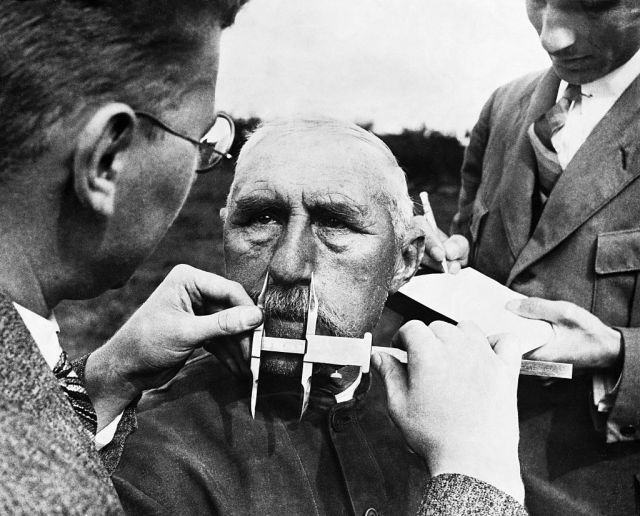

Nazi officials use calipers to measure an ethnic German’s nose. Credit: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty

Adam Rutherford is nervous. The science writer and broadcaster is worried about the publication of his remarkable new book on the vexed subject of science and race, How to Argue With a Racist. Even though his training is in genetics, he is still concerned that he got all the science right. It is, after all, an extremely complex area. And he tells me, in an interview which you can listen to below, that there are some aspects of it that only a few people in the world really understand.

But not only that. He is also grabbing, with both hands, a live rail of the contemporary culture wars: Laurence Fox, Meghan Markle, the re-emergence of ethnic nationalism, racism returning to the football terraces. And he doesn’t shy away from asking the dangerous questions: Why has no white man won the 100 metres at the Olympics since 1980? Are Ashkenazi Jews cleverer than anyone else?

Rutherford is also doing something rare among people who write about science: he is addressing, full-on, the history of the complicity of science and the Enlightenment with racism itself. Last year, he gave the Voltaire lecture for Humanists UK. Voltaire, he told them, was a racist. Voltaire wrote things such as:

“Our wise men have said that man was created in the image of God. Now here is a lovely image of the divine maker: a flat and black nose with little or hardly any intelligence.” (Romans: Les Lettres D’amabed. 1769)

Voltaire was not alone. The Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, who founded the taxonomical classification of living things that we still use today — Homo sapiens etc — categorised various types of people, linking physical features with what he believed to be character features. The group he called Afer — after Africa — were lazy, the females of the species were cunning and without shame. These associations were built into ‘race science’ from the very beginning. Little wonder Kehinde Andrews described the Enlightenment to me in his Confessions as “white man’s identity politics”.

Scientists have not always been good at this sort of self-critical attention to their subject. I suspect that the reason for this may be in part an overconfidence that self-criticism is built into the scientific method and that it is, therefore, already taken care of. This can sometimes mean that scientists allow themselves to get on with the business of science unperturbed by the wider moral implications of their work. Indeed, this has almost become a badge of pride: just follow the evidence, wherever it leads.

Over the years, Adam and I have rehearsed many of the rather tired old debates about science and religion. He goes: the inquisition and witch-burning; I go: nuclear weapons and a sea full of plastic. It’s all a bit knock-about, really — pub debates of the sort beloved of Twitter. But the conversation gets far more interesting when we start discussing what science might learn from the failure of religion. And, in particular, what science as the now dominant interpretative mechanism might take away from the mistakes made by the dominant interpretative mechanism that it has replaced.

I am not especially interested in the ‘science is a form of faith’ line of argument. But as dominant systems of interpretative power, science and religion do share many of the same features. They both have a kind of priesthood invested with the power to understand the world. The upper reaches of this priesthood conduct arguments that are beyond the ken of ordinary people. Both subscribe to a theory of history in which time rolls its way towards the inevitable unveiling of truth — science calls it progress, religion calls it eschatology. Both are invested with some sort of soteriological purpose: scientists, for instance, are often seen as the people who will save us from the coming apocalypse of climate break-down.

Rutherford thinks that one of the major differences between these systems of interpretative power is that religion became — eventually became — much more conversant and self-aware about the dangers of having power. What else was the Reformation about, for instance?

Science, a much younger discipline, is still working this out. It doesn’t help that science often refuses to accept that it is doing far more than simply following the evidence. After all, if you spend your days in a lab conducting detailed experiments on the hormones of the lesser spotted toad, or on the conductivity of crystals, it may seem odd to think of this as some great system of power, with danger as well as opportunity in its path. I am not taking a pop at science here. If anything, this is some friendly and well-intentioned advice from one system of power to its successor, pleading with it not to make the same mistakes.

And that is why Rutherford’s book feels so significant: the scientific method is no fail-safe prophylactic against moral failure. Even science requires self-critical vigilance. And it is in danger of missing this if it presumes that its own methodology has its vigilance built in, and so does not need attending to. At the very least, science is a human activity and the people who conduct it are as vulnerable to human failing as anyone else.

Rutherford’s story of science and race is a chastening one. The scientist Francis Galton was a scientific genius, Rutherford believes. But he was also an avowed racist and eugenicist. In 1913, and under his influence, this country came close to passing the Mental Deficiency Bill which would have prohibited marriage with the “feeble-minded”. It took Josiah Wedgwood MP two days of heroic filibustering — tabling 120 amendments and making 150 speeches — to see that one off.

Which is why I wonder if Rutherford’s important book has exactly the right title. One could be forgiven for assuming that Rutherford has found a way to use science as a way to confront base, common or garden bigotry. But the racist he is schooling us to argue with is not so much the racist of the football terrace, it is more the Galton-like racist of the laboratory. Or, rather, a dangerous crossover between the two — the sort of racist to be found in certain forums on the internet, like Stormfront and 4Chan, where bigotry is dressed up in scientific clothing. What used to be put in terms of purity of blood, now gets expressed in terms of DNA. So, for example, on Stormfront:

“… a great deal (possibly 90 per cent or more) of a person’s intelligence and character is determined by the DNA, which determines the structure of their brain before they are born. This is why Blacks, as a group, do the things they do.”

Rutherford debunks this brilliantly. What he shows, carefully and in detail, is that genetics, properly understood, doesn’t support any of this disgusting nonsense. There is no such thing as racial purity — because, among other things, if you go back far enough, your ancestors are also my ancestors, whoever you are.

The story of human history is one of migration and of people having sex “wherever and whenever they could” (his words), which means we are all ultimately related to everybody else. The ‘scientific’ racists hate this. It reminds me a little of the way some racists tried to conscript Christianity as a euphemism for white culture — right up until the point that it was pointed out that the Bible says that we all share a common ancestry, all children of Adam and Eve. They didn’t like that one either.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe