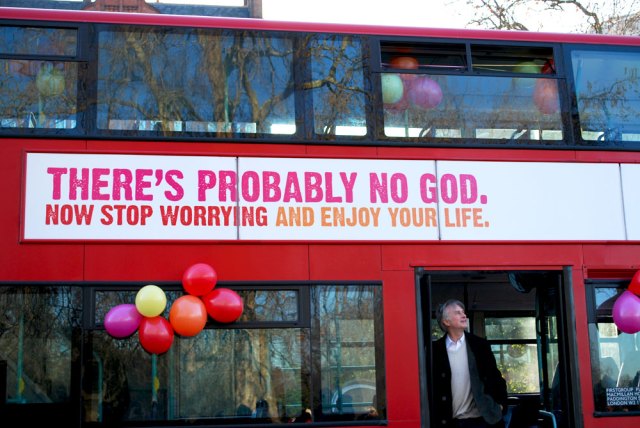

Richard Dawkins launches The Atheist Bus Campaign.

I can still remember the relief I felt on first reading Francis Spufford’s Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Still Makes Surprising Emotional Sense. It was published in 2012, a year that was perhaps the high-water mark of ‘New Atheism’, and proved to be an inflection point in the way religion was written about in public. My copy (or I should say copies, as I have bought, read and given away more than I can recall) is heavily underlined and splattered with marginalia.

Prompted, at least in part, by 9/11, New Atheism rumbled through the ‘noughties’. It was noisiest towards the end of that decade, thanks the self-described ‘Four Horseman of the Apocalypse’: Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett and Christopher Hitchens. Dawkins’ The God Delusion, Harris’ Letter to a Christian Nation and The End of Faith, God is not Great by Hitchens and Breaking the Spell by Dennett were all published in a cluster around 2007.

In 2009, British citizens were treated to the spectacle of the ‘Atheist Bus’ — a double decker advert declaring ‘There’s probably no God, so stop worrying and enjoy your life’ — created by the comedian Ariane Sherine with the support of, again, Dawkins.

The themes of the Four Horsemen’s treatises are now widely known: religion is dangerous and deeply irrational; only science, and the light of reason, can save humanity from the plague of superstition and violence it whips up.

Most religious responses took the bait. Some were shrill and ill-informed. The best, like The Dawkins Delusion by Alister McGrath, did a good job of exploding the facile underpinnings of most of the arguments, but didn’t succeed in changing the terms of the debate. Unapologetic did. The first chapter was serialised run in full by the Guardian, for one thing.

For another, Spufford is a real writer, a writer’s writer. Picked as Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year in 1997, he is unusual in publishing both critically acclaimed, commercially successful novels and books of non-fiction, as well as collections of essays. He is also a professor, teaching creative and life writing at Goldsmiths College. The book directly prior to Unapologetic was Red Plenty, about life in the USSR. This segue into religion came as a bit of a surprise, not least, apparently, to his agent.

So Spufford’s prose is hilarious and precise (but excruciating) as he acknowledges the worst caricatures of Christian belief: “Believers are the people touting a solution without a problem, and an embarrassing solution too, a really damp-palmed, wide-smiling, can’t-dance solution. In an anorak”. It helps that he has spent some time as an atheist. Spufford knows all the flaws and failings of religion. Yet he still wants to offer, not “a defence of Christian ideas [but] a defence of Christian emotions — of their intelligibility, of their grown up dignity”.

He moves the debate out of the zero-sum dingdong about the Big Bang and biblical archaeology and philosophical proofs — and into the realm of feelings. And not because feelings are just easier (the clue is in “intelligibility and grown-up dignity”) but because for almost all of us, that’s what drives not just our metaphysics, but most of our deepest decisions.

Spufford was not alone in pushing in this direction. Although he had been writing about it in academic circles since the late nineties, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt also broke into the mainstream in 2012 with The Righteous Mind. Building on his earlier work “The emotional dog and its rational tail”, he updated the metaphor as an elephant and rider. Our emotional, intuitive judgements are the elephant, actually in charge, and our reasoning minds construct post-hoc rationalisations for why we wanted to go that way in the first place. Daniel Kahneman — a Nobel laureate psychologist and economist had made similar arguments in Thinking, Fast and Slow the previous year — and the work of Ian McGilchrist, among many others over the decade, all contributed to this growing sense that we are not as rational as we thought.

In seeking to shift the debate about religion into the realm of emotions, then, Spufford was not dodging the “real question”:

“If I say that, from inside, it makes much more sense to talk about belief as a characteristic set of feelings, or even as a habit, you will conclude that I am trying to wriggle out, or just possibly that I am not even interested in whether this crap I talk is true”.

For the record, he does care, describing himself as a fairly orthodox believer who can recite the creeds. It’s not that he doesn’t think truth is important, but that arguments about whether God exists are self-defeating: “No, I can’t prove it. I don’t know if there’s a God (and neither do you, and neither does Professor Dawkins…it isn’t the kind of thing you can know. It isn’t a knowable item).”

Instead of getting stuck there, he agrees with the major move in social psychology and neuroscience this decade: “it is the feelings that are primary. I assent to the ideas because I have the feelings; I don’t have the feelings because I assent to the ideas”.

Crucially, he argues that this is true of everyone. It’s not only that religious people have faith because of their feelings — the opposite can be true:

“There are arguments to be made [against the existence of God]…but for a lot of people they function as a rationalisation after the event for a deep and emotional conviction that the universe is just not the kind of place in which such things can happen.”

The move is a good and persuasive one, but it’s the manner in which he writes about emotions that make the book so successful. There is no schmaltz; no earnest, dusty, churchy tone. Atheist philosopher John Gray called it, “a rare gem, a book that carries conviction by being honest all the way through”.

Whether describing sin — the crack in everything — as HPtFtU (the Human Propensity to Fuck things Up) or exploring the sense of divine mercy in Mozart’s Clarinet concerto, Spufford writes about the lived experience of faith more accurately and beautifully than anyone except Marilynne Robinson, Graham Greene and Dostoevsky (significantly all novelists).

People will still be reading this book once the new atheist polemics (and their religious responses) have been consigned to the recycling bin of history, because it is more powerful, more human, than any of them.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe