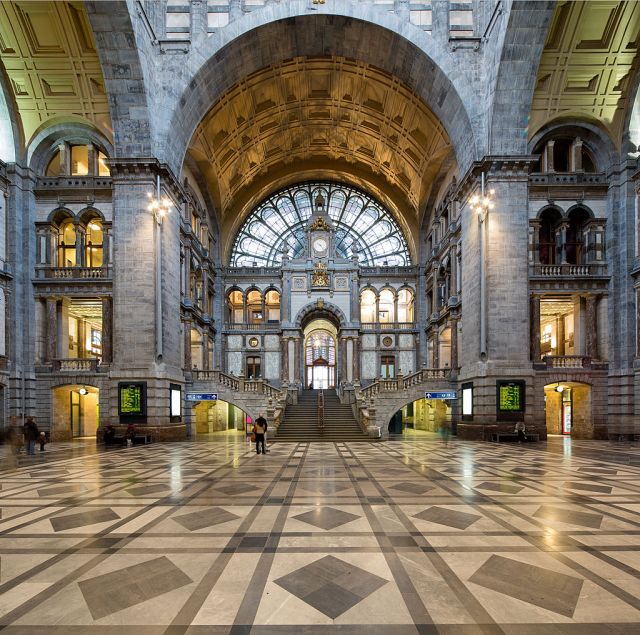

Antwerp station, symbol of the future we could have had. Photo: Getty

The New Year should have its Scrooge, and I am here and now volunteering for the post. This meaningless non-festival of made-up exultation leaves me colder than a January puddle. It has no redeeming features. What is it even about? In one of my childhood home towns, poor old Portsmouth, it is the tradition to blow the hooters of all the ships in harbour (not very many nowadays) as the year turns.

I have never heard a more dismal, pessimistic noise. It sounds like a great sea creature coming to the surface and dying, just over the horizon, a miserable thought. And quite right too. How much more fitting than the silly tipsy cheering of the shivering crowds in other cities, as they watch the futile fireworks and toast the turn of the calendar. Towards what?

There are people who, around this time of year turn out lists of wondrous material achievements and supposedly pleasing prospects which lie before us. There will be more electric cars, apparently, as if that is a good thing. On the contrary, innocent pedestrians and cyclists, such as I am, fear these silent killers. Their sole function, it seems to me, is to make motorists feel less selfish because the filth and noise these things create have been outsourced to a distant power station. Even the revival of the railways, which I at first welcomed, turns out to mean that travelling by train is more and more like travelling by air.

Now, when I make these accurate points, people accuse me of wishing to go back to the 1950s, a decade which — to me — has all the allure of an overflowing ashtray next to a plate of bad food. I have no such desire. I do not wish on New Year’s Eve to be transported back to the age of custard, chilblains and Giles cartoons. What I feel, when I pause to think of what lies ahead, is that we have an unerring ability to choose the wrong future. Architecture, of all the arts, seems to me to mock at us for this mistake. For it is the most powerful art of all, and it also persists long enough to remind of us of what we used to be and what we might have been.

Wander, as I love to do on autumn days, through the great cities of continental Europe, and you will begin to sense something very disturbing. Of course, there is plenty of loveliness in their ancient quarters, though it often finishes abruptly, up against some modernist cuboid or a swooping, perpetually growling motorway junction. And there is, increasingly, a frenzy of newness, as if there is a collective will to obliterate as much of the past as possible.

In the Netherlands, especially, there seems to be an almost hysterical desire to build tall, straight, featureless boxes at every opportunity. The Hague seems to suffer from this worse than anywhere else. How ruthless and crude it all seems in a city which once breathed Edwardian calm, with its stately parks and its foolishly optimistic Peace Palace.

But there is still an era in between, and this is the one which distresses me, because it is the relic of a future we nearly had, and which we threw away. The colossal Central Station at Antwerp, dating from shortly before the Great War, is perhaps the most moving example of this. It has opulence, grandeur and calm. It assumes that the world will remain solid, prosperous and peaceful. And, in its portly, slightly constipated way, it is exactly what all those ruthless, clean-lined tower blocks of today are not.

It is the inheritor of the old world of narrow streets, arches, spires and pinnacled towers, in which it was built. It respects the language of their architecture, one of a continuing Christian order and hierarchy. So, come to that, do the lovely millionaire’s mansions of Moscow, many of them preserved as embassies, and enough to make you weep at a world so irrecoverably lost amid Soviet new barbarism and Oligarch’s Baroque.

So do the light-hearted pinnacles and curves, still to be seen in Barcelona, of such Catalan geniuses as Antoni Gaudi and Lluis Domènech i Montaner. How might it have been if such minds — and the ideas that went with them — had dominated the building of the 20th and 21st centuries, not the thudding brutalism of Corbusier and Goldfinger, and their stark successors? Modern did not have to mean ferro-concrete. It just turned out that way.

How different the world before 1914 was. It is a punctuation point as stark as the Fall of the Roman Empire. Before: curves, Degas, detail, shadow, mystery. Afterwards: eye-searing light, straight lines, Otto Dix, unconcealed power and no mystery at all. Power needs no mystery. On the contrary, it is keen to be recognised as what it is, straight away.

From Antwerp’s great cathedral of railways, doubtless once perfumed with good cigars and strong coffee, one could have travelled, in carriages of polished wood, brass fittings and deep cushions, to any number of ancient, unspoiled cities, in which patient, cautious statesmen made their careful plans in high-ceilinged offices looking out on to broad boulevards traversed by trams, offices so quiet that you could hear the rustle of the ashes shifting in their open fires.

And they planned war. Had they not done so, I am sure that most of the great developments of modern science would have come about, perhaps in a different shape, perhaps a little more slowly. We would have had another sort of modern world, more civilised and more worthy of optimism, than the rackety arrangements we have now. We might have no television, but some other gentler invention. The self-evidently crazy idea of mass car ownership, the foundation of Fordism, might never have taken root. Why, social democracy might actually have been made to work and Russia could have become a liberal democracy.

But they chose war. And it was that war which ended all possibility of the future which we might have had. War took us from stately, mannered opulence to bare, arrogant expressions of strength and money. It ended the slow amelioration of old-fashioned social democracy and gave us Bolshevism. It obliterated conservatism and gave us fascism and National Socialism. And in the end it brought us to the deliberately materialist modernism of the European Union and the secular worship of material progress above all things, which we have now, and perhaps for a while longer.

The change in architecture, art, literature and music, which accompanied this transformation, tells us that there is no way back. We have, more or less, recovered materially from the disaster of 1914. But our ideas have not. We can no longer believe in the things we believed in before 1914, because they were discredited by war and what followed.

Above all, the supposed repression brought about by religious belief has gone. None of us, now, could bear to return to it even if we were offered the chance. Stefan Zweig’s World of Yesterday actually sounds rather appealing to me at this distance. I would in theory be glad if coarseness and violence once again became as shocking as they were to Zweig’s generation. But would I really be able to bear the stifling obedience to adults, the formality of dress, the interminable Sundays, the long postponement of pleasures during a lengthy and rigid education in which you could actually fail examinations?

The spirit which made all this possible, and which sustained the other many self-restraints which kept the peace, has gone. The simplest way of expressing this is that I would love to know great acres of poetry and Shakespeare by heart, and to be able to quote at will from the works of the classical thinkers. I would love to know Ancient Greek. But I would not love the self-discipline needed to do these things. I have simply not been brought up to such tasks, and the world around me, shouting for my immediate attention, will not let me pursue them.

But no amount of complacent or optimistic statistics about any coming year will ever persuade me that what I have is better than what I might have had, if we had chosen another future in 1914.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe