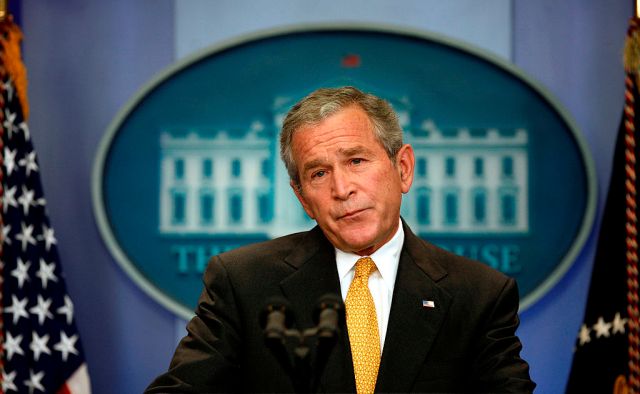

President George W. Bush in 2008. Credit: Aude Guerrucci-Pool/Getty

“I’m friends with George Bush. I’m friends with a lot of people who don’t share the same beliefs I have.”

The sight of Ellen DeGeneres and George W. Bush sitting together in the owner’s box at a Dallas Cowboys game was so unexpected, and caused such fierce debate across Hollywood, that the comedian felt she had to come out and defend herself. Opinion was viciously divided — and loud. Many of DeGeneres’ famous colleagues supported her cross-political companionship, while others condemned any association with Bush as beyond the pale.

Such was the fascination with this pairing, that a scene that wouldn’t have seemed out of place in a skit on a late night comedy show inspired the final question posed to Democratic presidential candidates during the last debate.

Laura & George Bush sitting with Ellen Degeneres and Portia de Rossi is not something I expected to see at an NFL game pic.twitter.com/AbWbhXd3RC

— CJ Fogler account may or may not be notable (@cjzero) October 6, 2019

This was a pivotal moment in President Bush’s long march back into the public consciousness. And it provides an opportunity to reassess one of the most polarising leaders in US history; he’s particularly useful at the moment, as he serves as a lens through which to view the current political divide in the United States.

George W. Bush’s presidency was divisive before it even started: he won the 2000 election, despite losing the popular vote due to the idiosyncrasies of the American Electoral College (sound familiar?) and a controversial Supreme Court decision over “hanging chads” (kids, look it up) in Florida. He was, in the eyes of many, illegitimate.

Support may then have soared at home and abroad in the immediate aftermath of September 11, 2001, and the early days of the War in Afghanistan. But his administration squandered all that goodwill with their adventures in Iraq (Bush found an eager ally in Tony Blair, who suffered a similar reputational collapse) and bullying foreign policy.

As the political baggage of two increasingly unpopular wars was compounded by the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression, Bush finally united Americans — in their disapproval of his performance. His approval rating bottomed out at 22% as he left office, retired as the least popular president in US history and arguably the most hated man in America.

But, over time, a curious thing happened. He recovered. To the extent that, by January 2018, a CNN opinion poll showed that Bush’s approval rating had nearly tripled from his end-of-term low, climbing to 61% (just a bit below Barack Obama’s rating at the time).

This means that about half of those who disapproved of him by the end of his presidency have turned their opinions around. And this bifurcation is not as simple as the Republican/Democrat divide; in fact, by 2017, even a slim majority of Democrats held favourable opinions of Bush.

So what’s caused the Bush revival? What is this middle ground hankering for? I suspect, to an extent it is the “absence makes the heart grow fonder” effect. Bush has kept a pretty low profile since retiring, and a significant number of his public appearances have been disaster relief events or showcases of his newfound passion for painting amateur portraits of dogs, world leaders and veterans (somehow, this isn’t a late-night sketch either), not exactly the most offensive material.

Bush also made several public appearances during various periods of mourning, including at the memorial of his intra-party political foe John McCain and the funerals of his mother, Barbara, and father, George H.W. Bush, all of whom died last year. These were also occasions at which his other unlikely but very real friendship — with former First Lady Michelle Obama — became obvious. And surely anyone who’s friends with Mrs Obama must have something good going for them.

It also helps that there is obviously no love lost between Donald Trump and the Bush family. Trump basically bullied Jeb Bush out of the presidential race in 2016, and destroyed the TV career of Bush cousin Billy with his vulgar conversation with the then-host of Access Hollywood. The Bushes have given Trump the cold shoulder ever since.

Sure, President Trump has set a low bar against which any ex-president can stand favourably — using military aid to Ukraine for political purposes, for example, and telling mostly American-born minority congresswomen to “go back” to their countries to name only two controversies to date. But there’s a more specific quality that “W” possessed which has been lacking in American politics in recent years: sincerity.

Throughout his political career, Bush presented himself as an honest straight shooter: even if you didn’t agree with him, you knew where he stood. This attitude largely came from his Evangelical faith, which drove many of his policies and provided him with a fairly unflappable base. That base remains loyal. You could sense it when Donald Trump attacked the Iraq War as part of a defence of his Middle East policy during a recent speech at the Value Voters Summit in Washington DC; the previously enthusiastic Evangelical crowd grew noticeably quiet.

To the delight of Bush’s Evangelical supporters — and the horror of liberals and libertarians dedicated to the strict separation of church and state — President Bush wore his faith on his sleeve. The Evangelical label has, of late, become more of a political term than a religious tag, signifying a certain brand of American conservativism, Bush’s faith went beyond the political. Both Bush and his wife, Laura, publicly credited his conversion (with an assist from legendary preacher Billy Graham) with helping him end his drinking and hard-partying ways at the age of 40, paving the way for his political career.

Bush’s policies were inextricably linked to his faith. He labeled his approach “compassionate conservatism”, and while other Republicans have cynically abused this slogan, Bush seemed to genuinely value both halves of it.

He was surely conservative, a son of the Religious Right that had brought Ronald Reagan and Bush’s own father into the White House. The George W. Bush administration had hardline approaches to abortion and same-sex marriage. It banned stem cell research, and channeled money to religious groups through its Faith-Based Initiatives program.

But Bush also expanded Medicare access, proposed immigration reform that included a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants already in the United States, and increased aide to sub-Saharan Africa. These policies may be anathema to the current Republican leadership — but they make sense under a genuine commitment to the compassion that Bush claimed. To moderate Republicans today, approval for Bush represents nostalgia for a version of conservatism that could credibly, even proudly proclaim to have the best interests of the country and the world at heart.

On the other side of the political fence, moderate Democrats remember that even when there were sharp policy disagreements between the Bush administration and those on the Left, few people (Kanye West aside) could accuse him of basing his policies on animosity towards any groups of Americans.

Educators and reformers may have opposed Bush’s No Child Left Behind education reforms, but it was clear that he genuinely sought to combat “the soft bigotry of low expectations” regarding America’s worst-performing public schools. His anti-abortion stances and opposition to marriage equality may have been driven by religion, but they weren’t fueled by misogyny or homophobia; Bush did not resort to trotting out the “some of my best friends are…” defence for his policies, but his wife, Laura, apparently helped soften his political stance on same-sex marriage out of respect for their same-sex couple friends (whom, we now know, include Ellen and her wife, actress Portia DeRossi).

In contrast, Donald Trump has presented a presidency rife with prejudices and aspersions against various groups, seemingly unguided by any larger sense of purpose or philosophy (and some would say completely unguided by morality more generally). And he is unchallenged by any Republicans of principle. They have either retired (like former Speaker of the House Paul Ryan) or have decided that having a Republican in the White House with a rabid voter base was worth the price of swallowing their own principles (see Senators Ted Cruz, Lindsey Graham and even Majority Leader Mitch McConnell).

Outside of Evangelicals, whose fervent (but possibly wavering) support for Trump has not displaced their allegiance to Bush, the Trump wing of the party sees Bush as part of the Right-wing establishment that Trump overpowered during the 2016 Republican primaries. The anti-Bush Trump supporters include white nationalists, previously fringe elements of the conservative movement who have been courted by Trump but thoroughly condemned by the Bush family.

This cohort sees the Iraq War, in particular, as the albatross around Bush’s neck. While most Republicans remain supportive of the decision to go into Iraq, the Trump wing considers it to have been a colossal waste of lives and money. They have singled out this particular military adventure as the source of America’s current open-ended commitments in the region and its “never-ending wars” — despite the fact that America has been deeply embroiled in the Middle East for decades. And while Bush was criticised at the time for going to war war really being over oil, Trump himself has recently castigated Bush for not actually seizing the oil to America’s profit; in other words, they fault Bush for not actually measuring up to the crude caricature they painted.

On the other extreme, the current crop of Democratic challengers are pulling to the Left with ever-increasingly liberal policies that seem at times to be more about virtue signalling than practical visions for the country. (I can’t help but think that the voter desire for political sincerity, which Bush so appealed to, is why Bernie Sanders, the candidate who was socialist decades before it was cool, remains a viable force, even as younger and healthier candidates have vied for his position on the Left.)

For these resolute Bush detractors on the Left, the Iraq War was not only a mistake but a crime. Bush and his advisors (Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and others) were not straight shooters or patriots, but cynical opportunists who concocted a false story of Weapons of Mass Destruction to launch an invasion in order to gain access to Iraq’s oil reserves. “Bush lied, people died”.

Beyond lingering feelings about the Iraq War, the renewed animosity toward Bush among progressives has been fed by two trends currently occupying the Left: cancel culture and anti-wealth sentiment. The criticisms lobbed at Ellen DeGeneres by some of her Hollywood colleagues centre around this idea that President Bush should be regarded as a war criminal, and absent some kind of legal accountability, should at least be shunned from public life. Both Tim Robbins and Avengers actor Mark Ruffalo, have chided the comedian for her personal choices.

Her friendship has also been used to further the Left’s obsession with class antagonisms. For these progressives, the fact that a lesbian, liberal talk-show host could pal around with a staunch religious conservative who opposed not just same-sex marriage but many of DeGeneres’ values, well, it just goes to show that wealth trumps everything else in American politics.

Ellen and W may be divided by ideologies and beliefs, the narrative goes, but they are nonetheless joined together in a plutocracy that is out of touch if not actively hostile towards average Americans. DeGeneres herself has joked about her lifestyle in the ironically-titled standup special Relatable, but now she and George W. Bush are being cast as members of an ultra-elite who need to be put in check for the good of the country.

It is, I believe, a mistake to think the American public is poised to demonise wealth. In any case, even though Bush is rich, he has not been one to particularly flaunt that wealth (tax cuts during his presidency notwithstanding). And furthermore, the fact that Iraq did emerge with its own elected government, no matter how dysfunctional, and with control of its own oil fields somewhat blunts the worst of their condemnations of the war as a complete sham or failure.

Many Democrats, meanwhile, are watching their party leaders enact increasingly stringent purity tests and an unwillingness for dialogue, much less forgiveness, for those who violate progressive norms or even associate with violators. These standards are, for many, impossible to keep, counterproductive to real progress, and represent the replacement of practical politics with disingenuous virtue signalling.

Essentially, in an era when Trump has taken hold of the reins of Republicanism, and his most prominent critics within the party have died, retired or capitulated, the public rehabilitation of Bush represents a nostalgia for a party that was both conservative and principled.

Compared to current insincerity, nihilism or extremism dominating politics in the United States, many Americans find themselves longing for the days of a true believer. For them, it was refreshing to see a conservative Christian and a gay Hollywood liberal daring to be seen talking to one another, a scene that increasingly feels like a comedy sketch because it is so far removed from real politics today.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe