Yellow vest demonstrations in Paris, France. Credit: Mattia/Getty Images

Patient Zero is the trope of many a zombie movie — the first person to be infected with the deadly virus that is destroying the world. Sometimes Patient Zero must be killed to stop the virus spreading. Sometimes Patient Zero is the means to find the cure. Whatever angle the story takes, the solution lies with Patient Zero.

A society has its own Patient Zero, a way by which many of its ills can be remedied. Patient Zero is its system of tax.

Taxation, like death, sadly, is inevitable. In all the years since man settled on the fertile plains between the Tigris and the Euphrates, there has never been a civilisation without taxation. In fact, a sense of duty to the greater collective probably existed in the hunter-gatherer tribes that pre-dated civilisation.

Yet there have been good systems and bad systems. Get your system of tax right, and a healthy and happy civilisation, even a great one, will follow. Get it wrong and you get no end of problems, for history is littered with examples of injudicious or inequitable taxation having terrible consequences. It lurks near the heart of virtually every great revolution or revolt.

“No taxation without representation” was the cry of the American revolutionaries. Punitive taxes led the French to rise up against their decadent leaders in 1789, and the English peasants to do the same back in 1381. Perhaps most explicitly, the Philippine Revolution began with the Cry of Pugad Lawin, exhorting rebels to tear up their tax certificates. From Spartacus to Boudicca to Robin Hood to Mahatma Gandhi, the greatest rebels in history were usually tax rebels.

Even today, there is evidence of this — just across the Channel, where heavy fuel taxes have resulted in the riots of the gilets jaunes.

A society’s destiny — whether its people will be prosperous or poor, free or subordinated — is determined by the way it is taxed. How much of a labourer’s labour is his to keep? How much is taken from him? The way a society is taxed speaks volumes.

In the enlightened civilisation that was ancient Athens, taxes were voluntary. Liturgy — “public service” — was the means by which the rich shared their wealth with the rest of the city. Not only did the rich pay for essential public works, whether it was a bridge or a warship, they carried out those works as well — on their own terms.

At the turn of the 20th century in western Europe, tax was running at around 10% of GDP, slightly lower in the US. This dates back to the historical norm of the tithe, a tax which goes all the way back to Mesopotamia. Two world wars, however, ended the halcyon days of low taxes.

At the other end of the spectrum, in authoritarian or totalitarian societies such as Soviet Russia or North Korea, ordinary people have virtually no ownership of their labour, their produce or their profit. Government takes it all.

The developed world today sits somewhere in the middle of those two extremes. Excluding inflation (itself a form of tax), in Britain nearly half of everything you will ever earn over the course of your life is taken from you in taxes. The most expensive purchase you ever make is not a house, as many believe, but your government. In France the figure is an eye-watering 57%. No wonder the gilets jaunes are so unhappy.

The idea behind social democracies’ high levels of taxation is that wealth is redistributed to equalise life chances — but how successful has that redistribution been? Economic inequality is rampant. Every year Oxfam puts out incredible statistics stating that just eight men own the same wealth as half the world. Billionaire wealth rises at six times the speed of an ordinary worker’s; a CEO makes in a day what his cleaner makes in a year. So much of the unlevel playing field that is the 21st century developed world economy can be traced back to inequitable systems of tax.

About the only way a young person, starting out with nothing, has to better their lot is through their labour — by working — and yet the worker pays the vast majority of taxes: roughly 50% of government revenue in the developed world comes from income tax (in the UK this includes National Insurance) with another 20%, roughly, from VAT. We tax labour constantly and heavily.

The wealth of the super-rich does not derive from their labour, however — with the exception of a few star sportsmen and CEOs. It comes from the appreciation in the value of their companies, their land, their houses, their stocks, their shares, their bonds, their fine art — what economists call their assets. These go untaxed, unless you sell — so most don’t. One group is taxed heavily, the other is not. Inequality is the inevitable result.

Not only is the worker taxed heavily, he is paid in money that loses its purchasing power, thanks to zero interest rate policies, Quantitative Easing, dubious measures of inflation and all the other means by which governments debase money and levy what Milton Friedman called the inflation tax. But these same assets that go untaxed — equities, houses and so on — actually benefit from the debasement of currency, as they appreciate in price. One lot pays, the other benefits.

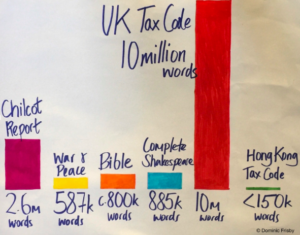

Modern tax systems — with a few notable exceptions such as Hong Kong and Singapore — are blighted with complexity. The UK is the worst offender, with a tax code that is the longest in the world: 10 million words and 21,000 pages. The code is about 12 times the length of the Bible! Ten million words is more than most people read in their lifetime.

The table below, taken from my Edinburgh Fringe show of 2016, puts that number in some kind of perspective.

The longer a code is, the more loopholes there are. One group have the resources to find the loopholes, especially multi-nationals, and exploit them; the rest of us don’t and so pay more on a proportional basis. The result is inequality.

Hong Kong proved one of the most successful economies of the second half of the 20th century, going from shanty town to futuristic city-state in barely 50 years. It did so with taxation that never exceeded 14% of GDP, and in which only the very rich paid income taxes. On the supply side its education, health and transport systems are all superior to our own. Its code is 1.5% the length of the UK’s.

Yet it had one tax we do not have — a tax on land value.

With 60 million acres and a population of 65 million, there is enough land in the UK for everybody, in theory, to have an almost acre each. Yet about two-thirds of UK land is owned by fewer than 6,000 people. In many cases they receive subsidies for the land they own; the ownership of prime city real estate is the domain of the few, while an entire generation cannot afford anywhere to live. Yet houses don’t cost a lot of money to build.

We should tax land, not labour! If a politician really wants to get to the root of society’s ills, and make them good, then he or she should focus all their efforts on tax reform. If only all the political effort that has gone into stopping Brexit had instead been expended on reforming taxation, oh, what might have been!

It is from our system of taxation today — bloated, inequitable, antiquated — that so many of society’s ills emanate. But it is also in our system of taxation where the cure lies. Fix tax, and you are on the way to “fixing” society. The rest will take care of itself. Tax is Patient Zero.

Daylight Robbery – How Tax Shaped the Past and will Change the Future is published by Portfolio Penguin.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe