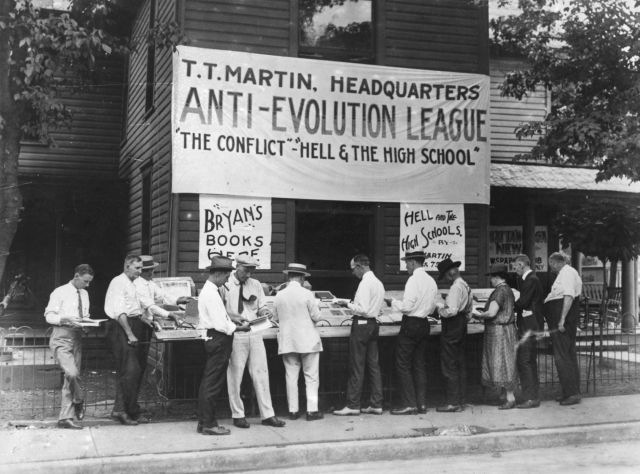

Anti-evolution books on sale in Dayton, Tennessee, where the ‘Monkeyville’ trial of Professor John T Scopes took place. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The Scopes Monkey Trial, which took place in Dayton, Tennessee in 1925, is one of those episodes in modern American history that almost everyone has heard enough about to feel they have a good grasp of the story. It is up there alongside Rosa Parks, the assassination of JFK, and Watergate.

The public’s perceptions of the trial have been shaped and coloured by films, plays and TV dramas — as well as by glancing references in newspaper articles, dropped names and conversational asides, all of which make up the currency of popular culture.

The episode’s urtext was Jerome Lawrence and Robert Lee’s play, Inherit the Wind, which was turned into a 1960 movie directed by Stanley Kramer and starring Spencer Tracy. The trial generated at least three further feature films, including a remake of Inherit the Wind, and four or five made-for-television docudramas. The film Planet of the Apes, in which the intolerant orangutan religious authorities refuse to listen to the scientific evidence of their connection to mankind, as presented by the liberal chimpanzee scientist, was a clear allusion to the event.

If one were to frame a composite picture to capture the impression of the trial passed to the following generation, it would look something like this: an earnest, high-minded young schoolmaster, John Scopes, who reads widely and keeps abreast of intellectual progress, decides to teach his pupils about Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, which is by now more than 60 years old and is accepted by biologists as scientific fact.

Scopes is motivated by a commitment to the welfare of the young minds in his charge. He is determined to give them an education founded on truth, rather than superstition. He obtains a set of textbooks and starts teaching evolution.

The pupils are gripped and want to learn more. However, Scopes’s initiative falls foul of a fusty, outdated law that forbids the teaching of evolution and requires him instead to teach the creation story set out in the Bible; this Scopes knows to be wrong because fossil evidence, combined with what he has read in Charles Darwin’s book, proves that the world is many millions of years older than a literal reading of the Book of Genesis allows.

But Scopes is also up against powerful interests, politicians and clergymen of reactionary disposition who feel very threatened, Darwin’s work being radically subversive of their source of authority and power. The issues at stake are academic freedom, freedom of speech, the separation of church and state, and supremely, the claims of scientific truth to a place at the top of the epistemological tree.

The case comes to court, where a thrilling duel of wits ensues between two of the finest trial attorneys in the land. For the defence steps forward the urbane Clarence Darrow, representing science and progress. For the prosecution, William Jennings Bryan, the epitome of a fast-fading order, in outlook and attitude somewhat similar to one of the more hardline figures on today’s evangelical Christian Right.

To begin with, it seems the prosecutor has the edge. The jury are simple country folk, and he plays to their natural conservative prejudices. Darrow, by contrast is a big city boy, and his slick ways elicit the jury’s suspicion.

Soon, the tables are turned. Bryan had hoped to put Darwin on trial, but the wily Darrow has put the Bible on trial instead. Not only that — he has put the prosecutor on the stand. The old man makes an almighty fool of himself trying to explain how God made the world in six days.

As the young schoolmaster comes blinking into the sunlight having been thoroughly vindicated, his young pupils swarm around him. Now they can go on to become research chemists or geneticists. Heck, the geeky one with the specs might even win the Nobel Prize. For sure, anyone with a broadly liberal outlook stands with Scopes and is firmly of the Darrow persuasion.

But almost everything we think we know about the Scopes trial turns out to be untrue. Scopes wasn’t really a science teacher: he was the high school’s football coach and only covered science when the regular teacher was away. He probably never actually taught his class about evolution at all. Scopes gave a number of conflicting accounts: that he did teach the lesson; that he set a chapter of a textbook as homework, but never taught evolution in the classroom; and, most credibly, that he had made the whole thing up. For the trial itself was a cynical contrivance.

The plot had been hatched around a table in Fred Robinson’s drugstore by a group of Dayton businessmen. One of them had spotted an advertisement in a city newspaper placed by a pressure group wanting to find a community willing to challenge the law forbidding the teaching of evolution.

Robinson, who styled himself “the hustlin’ druggist”, and his fellow small- town boosters, spotted a commercial opportunity. A spectacular trial in Dayton would pull in visitors from all across the United States, who would spend more dollars in local shops, hotels and restaurants every day the trial was in progress than local residents spent in a month.

John Scopes was invited to meet the business leaders on 5 May 1925. They made their pitch: he was a young man, 24- years old, with nothing to lose. He could become famous. They would see to it that whatever the outcome, no harm would come to him. He would be doing the whole community a favour. Scopes agreed, saying that he disapproved of the law anyway. Arrangements were made for the young teacher to confess to teaching a class about evolution in breach of Tennessee law.

The relevant statute, known as the Butler Act, was not a fusty old one. In fact the Governor had signed it into law only two months previously. The Tennessee House of Representatives had passed the bill by 71 votes to 5; the state Senate endorsed it 24 votes to 6. These margins reflected the Butler Act’s enormous popularity among the people of Tennessee — and there was good reason for that.

At this time almost everyone who considered themselves ‘progressive’, including everyone who considered themselves a ‘Darwinist’, strongly supported the-then rampant eugenics movement. In rural Tennessee, folks may not have had a sophisticated grasp of Darwin’s theory of evolution, nor of his cousin, Francis Galton’s related, but pseudo-scientific theory of eugenics; but they knew the progressives who preached Darwinism in the cities despised country people, called them “imbeciles” and “defectives” and would sterilise them if they got half a chance.

More than 60,000 Americans were forcibly sterilised under eugenics laws passed by 33 states. It wasn’t just low IQ that established someone as likely to have a dysgenic effect: a history of heavy drinking, or conceiving a child out of wedlock, were enough to mark someone down as a “moral imbecile”.

Neighbouring Virginia would witness vast sweep operations where road blocks were set up and teams of sheriffs’ deputies dragged whole families away to be put under the knife. But Tennessee held out, refusing ever to pass any compulsory sterilisation statute, and the people of the state distrusted the progressives. They understood that they didn’t just view southern hillbillies with contempt, they despised God and the Bible, too — and now they wanted to teach children that grandpa was descended from an ape. The Butler Act would put a stop to that nonsense.

The textbook John Scopes pretended to have used to teach his class about evolution was George Hunter’s A Civic Biology, a work that was consistent with the scientific orthodoxy of its day. That is to say, it was strongly influenced by scientific racialism and eugenics.

Hunter, like Charles Darwin before him, believed the several races of man had travelled different distances down the evolutionary road. Way out in the vanguard was the refined Caucasian; lagging at the rear was the significantly less evolved African type, with other races somewhere in-between.

Scopes accepted this doctrine of white supremacy. In preparing for the trial he had visited one of the scientists who, in 1906, had supported the exhibition of a Congolese Pygmy in a cage at New York’s Bronx Zoo, alongside an orangutan and a gorilla, as living proof of Darwinian evolution, presenting him as a transitional form between ape and human, the so-called ‘missing link’.

Hunter’s biology textbook was also scathing about what the author perceived as a feckless underclass that drank too much and lived off handouts. Compulsory sterilisation was his preferred solution.

As the town’s business leaders had hoped, the trial did pull in thousands of visitors. Dayton got its spectacle. The area around the courthouse soon began to resemble a carnival. A troupe of live monkeys cavorted on the courthouse lawn. More than two hundred journalists turned up, two of them all the way from England.

The man they had come to see perform, William Jennings Bryan, was certainly no prototypical Pat Robertson or Jerry Falwell. In fact, he was more of a Bernie Sanders. Bryan had been Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state and was three times the Democratic Party’s candidate for the presidency of the United States.

He was by some way the most politically Left-wing Democrat ever to receive the party’s nomination. The scourge of Wall Street bankers and big business, Bryan argued for a minimum wage and subsidies for poor farmers. He demanded the nationalisation of key industries such as the railroads, and the telegraph and telephone services. He was a radical populist and also a devout Presbyterian.

Since the defence admitted that Scopes had breached the statute, the only line left to pursue was to demonstrate that the creation story in Genesis was intrinsically risible. But when Clarence Darrow put William Jennings Bryan on the stand in Dayton, he did not inflict the comprehensive humiliation that posterity somehow remembers. He was evidently surprised by the answers he got when he pressed the witness on key points relating to the age of the world. Bryan may have been a fundamentalist, but his fundamentalism turned out to have its shades of grey.

The six days God had taken to create the world were not necessarily 24-hour days, Bryan explained. They might well have lasted millions of years, even hundreds of millions of years. Science and the Bible were not mutually exclusive. For the court, this answer meant that Darrow’s inquisition had no real evidential value and the judge swiftly brought it to a close.

Darrow and Scopes had failed to win the central argument on which the case turned. The jury took only nine minutes to reach their verdict: John Scopes was guilty as charged. The judge slapped the schoolmaster with a hefty fine. Which only goes to show that history is sometimes written — or re-written — by the losers.

Dennis Sewell is the author of The Political Gene; How Darwin’s Ideas Changed Politics

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe