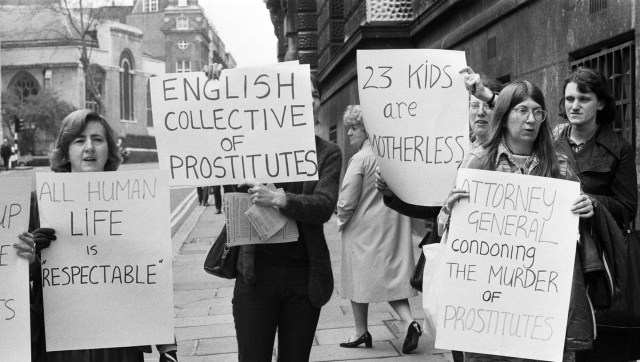

Protesters against the judge’s distinction between prostitutes and ‘respectable women’ during the Yorkshire Ripper case. Credit: John Varley/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

The last few years of politics have tested loyalties and fractured tribes; for many, it’s tempting to disengage altogether. We have asked contributors to remind us of why politics matters, by reflecting on their formative years. This series of political awakenings shows how family, feelings and unlikely accidents can shape a lifetime of politics…

One night in November 1980, I was followed on my way home from the pub. I was 18, newly arrived in Leeds and living in a YWCA hostel. At the time, the young women of northern England were living under a reign of terror; a serial killer operating in the region had already killed 12 women.

The man who followed me was of medium height with a dark, full beard, wiry hair and black, piercing eyes. I ran into another pub and managed to shake him off. Friends persuaded me to report it to the police and I completed a Photofit, but it was obvious that the officers weren’t taking me seriously.

The next day, the body of the serial killer’s final victim, Jacqueline Hill, was found less than half a mile from where I was followed. It was another two months before Peter Sutcliffe was arrested and confessed to her murder. When his photograph was published, it almost exactly matched my Photofit.

Sutcliffe, nicknamed ‘the Yorkshire Ripper’ by the tabloid press, turned out to be an ordinary, married man living in a suburb of Bradford. His crimes brought attitudes about women in general, and prostituted women in particular, out into the open — and it was in response to this shameful misogyny that I became a committed feminist.

Sutcliffe’s first murder victim — 28-year-old sex worker Wilma McCann — had been discovered in 1975 and, right from the beginning, the West Yorkshire Police were guilty of dragging their feet and bungling the investigation. Complacent officers overlooked vital clues, and inadequate technology was used to collate interviews and intelligence reports. And all the while, Sutcliffe just kept killing — with hammers, screwdrivers and knives.

Partly to blame for their failure to track him down was their assumption that the Ripper was only interested in prostituted women — when, in fact, only a minority of his victims were involved in the sex trade. On 30 June, 1977, an open letter from the Yorkshire Evening Post to Sutcliffe said, “Your motive, it’s believed, is a dreadful hate for prostitutes — a hate that drives you to slash and bludgeon your victims,” Such women, in the eyes of many, were complicit in their own demise, or even deserved their fate — rape and murder being mere occupational hazards.

This mythology meant that police excluded a number of cases of women found murdered in England because they did not fit the profile. They failed, for instance, to listen to one of Sutcliffe’s surviving victims: Tracy Browne, 14 at the time, managed to get a good look at the man who chatted to her about the weather, before striking her about the head several times with a hammer. When she reported the attack, Tracy was shown the Photofits compiled by other survivors and told police she believed it to be the same man. But they dismissed her evidence because she was not engaged in prostitution.

As a result police were no closer to identifying Sutcliffe by the time they found his fifth murder victim — Jayne MacDonald, who also did not fit their profile — in June 1977. The killing was described by police and press as a “tragic mistake”: she was 16 and described as “respectable and innocent”. Victims were duly divided into deserving and undeserving women.

When MacDonald was murdered, I was 15 and already thinking about feminism. I had been outed as a lesbian at school, where girls were judged either slags or lesbians by the boys who were the ones doing the naming and shaming. Sexism within popular culture was neither subtle nor occasional in the 1970s, and I learned that sexual violence was endemic in reality and widely viewed as entertainment.

In 1979, I moved from the North East of England to Leeds, where I met a group of radical feminists who were campaigning against male violence towards women and girls. At that time, their main focus of the group was challenging the appalling attitude of the police and journalists towards the victims and potential victims — and all women were potential victims — of the Yorkshire Ripper.

During Sutcliffe’s reign, ordinary men in the north of England loved to make jokes about him. “There’s only one Yorkshire Ripper”, football fans would chant; “Ripper 12, police nil”, was one particular jibe during Leeds United football matches where the police were penalising unruly fans; “Give us a kiss, love, I’m not the Ripper” was a regular crack heard in nightclubs around the country. A group of anarchists even named themselves The Peter Sutcliffe Fan Club because they saw him as the ultimate rebel.

Men would refer to Sutcliffe’s victims as sluts, slags and whores; they had it coming, blokes would say. I heard it from men on buses and on the streets. In the Post’s open letter of 1977, Sutcliffe was asked how he felt knowing that he had killed an innocent victim rather than a prostitute. Surely he felt remorse about his mistaken killing of the “respectable” Jayne McDonald?

Sutcliffe’s killing spree and responses to it from the police, media and much of the general public opened my eyes to the toxic level of misogyny within our society. I learned that women’s lives are worthless in relation to men – especially when those women are, as the northern phrase goes, “No better than they ought to be”.

Misogyny is borne from boys who are raised to consider women as lesser beings — little more than a commodity to be used and abused. It is precisely because men are afforded power over women under patriarchy that sexual violence exists. Feminism, which is my core political belief, will ultimately liberate women from male supremacy.

Femicide — the slaying of women by men — is a pandemic worldwide. When feminism achieves its aims, there will be no more Sutcliffes, and no more raped and murdered women and girls stacked up in morgues. For this, and a million other reasons, every woman should be a feminist.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe