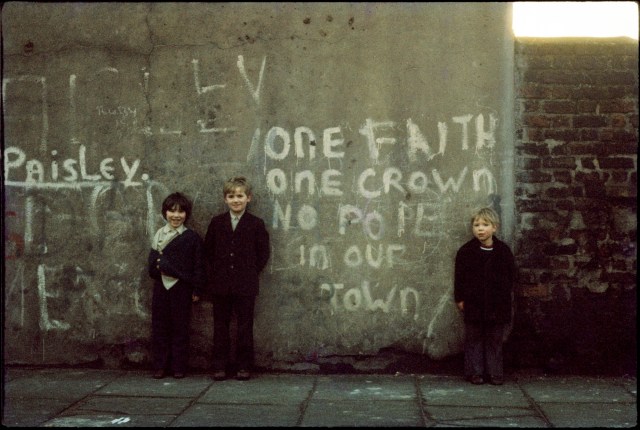

Sectarian graffiti in the Protestant Shankill Road district of Belfast, 1972. Credit: Alex Bowie/Getty Images

I was born in a particular place, at a particular time — Belfast, March 1971 — when politics had already run amok: it had broken out of government and city councils and spilled angrily onto the streets. By the following year, in March 1972, devolved government had collapsed and direct rule from Westminster was introduced.

That year, from one March to the next, saw rising IRA and loyalist paramilitary violence, the introduction of internment, and the fateful events of Bloody Sunday, on which British army paratroopers shot dead 13 unarmed demonstrators at a Londonderry civil rights march. Thereafter, things descended into greater mayhem: the summer of 1972 ushered in Bloody Friday, on which 20 IRA bombs exploded across Belfast in different locations.

I was too young to be aware of such events, but by the time that I was even dimly cognisant of our contorted politics — in the mid-to-late 70s — individuals and political patterns were entrenched in ways that were to endure for decades. Ian Paisley, who began as a young loyalist firebrand, had by 1971 gained both a Westminster seat and his own party, the Democratic Unionists.

Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness had been identified as key representatives of the IRA when they were flown to London for secret talks with Willie Whitelaw in 1972. By 2007 such “players”, formerly of the extremes, were firmly at the centre, and in charge: Paisley and McGuinness were leading a new Stormont government as First and Deputy First Minister respectively.

The family that I grew up in was pro-Union and Protestant but non-sectarian. My father was a barrister and also an independent Unionist politician, but I had little notion of Catholics as alien: we had Catholic relatives and family friends. It seemed to me that aspiring to a united Ireland by peaceful means, like an attachment to union with the UK, was a justifiable political viewpoint that could be debated.

The heavily electrified dividing-line lay not in religion or political views, but in the means you were prepared to use to get there. Both the republican paramilitaries (the IRA and the INLA) and the loyalist paramilitaries (the UVF and the UDA) openly considered it acceptable to murder people in order either to advance the cause of a United Ireland or to defend the status quo in the United Kingdom. They had a broad and elastic range of “legitimate targets”.

Sometimes the “legitimate targets” were politicians. When I was at primary school in 1981, the IRA shot dead the Ulster Unionist MP Robert Bradford at his South Belfast constituency office. Two years later, the IRA gunned down the young unionist politician and law lecturer Edgar Graham, in the grounds of Queen’s University opposite my secondary school.

Other brutal killings of politicians stuck in our communal memory — back in 1973, Loyalist paramilitaries had murdered the nationalist Senator Paddy Wilson and his girlfriend, Irene Andrews. Both unionist and nationalist politicians were routinely offered personal protection weapons. The entire society was permanently mined with unease.

By the time I was 10 or 11, it was clear to me that, once the dehumanising of the people on the other side of the political divide got started in earnest, some very dark territory awaited. Separately from that, it was becoming evident that the pro-Union position in Northern Ireland was a psychologically complicated one. It involved a loyalty to Great Britain and a shared history cemented in the losses of two world wars, combined with constant insecurity about the degree to which the affection was requited.

Northern Irish unionists were British in Ireland and Irish in Britain. They belonged to neither nation’s mythic conception of itself. The wider Northern Protestant tradition contained plenty to be proud of — its history of dissent, its industrial capabilities, writers, musicians and sporting heroes — but too often an intensely localised culture of Orange marching bands and gigantic bonfires drew negative media attention and threatened narrowly to define it.

No broader tribe was waiting to welcome Northern unionists warmly, and in any case — from what I could see — tribal loyalties had a way of turning nasty. Although a sense of identity is important to everyone, I began to be suspicious of any overweening communal identification that overrode individual values.

*

I have now lived in London for 25 years. Part of England’s appeal used to be the calmer way in which politics was discussed. Yet something else felt different in London too: a more acute class consciousness. In recent years it has become increasingly apparent to me that, in many ways, class is to England what religion is to Northern Ireland.

George Osborne, as Chancellor of a government heavily dominated by former pupils of England’s leading public schools, pressed home an austerity budget in 2012 with the words: “We’re all in this together”. We weren’t, of course. A report for the Institute of Fiscal Studies in 2015 found that low-income families with children bore the brunt of the coalition government’s austerity drive.

Official austerity collided with a new style of labour market — the rise of zero-hours contracts, without holiday or sick pay — and an overheating UK housing market, mingled with a severe shortage of social housing. The combination has, in recent years, seen the emergence of the “working poor”, who struggle to make ends meet despite being in employment.

The Leave vote was in part an expression of political frustration from those in England and Wales who had felt marginalised by their new set of circumstances and wished to return their government to more direct accountability.

If many low-income Leave voters seemed unconcerned about the potential economic effect, that is partly because the system was already working out so badly for them that they preferred to accept even a short-term worsening of their circumstances in exchange for a gamble on a different long-term deal. It may be a gamble in which the odds remain stacked against them, but it was not wholly irrational.

There were many means by which this polarisation by geography, class and age — evidence of which bubbled up after the referendum — could have been avoided. One such means lay in how different social groups talked — or rather, didn’t talk — to each other.

Over the decades that I have lived in London, I’ve gradually noticed a broader contempt for the working class creeping into both public policy and the language of the more socially influential and financially secure — the notion that, if poorer people were failing to rise, it wasn’t because of any barriers placed in their way, but because they were simply what the UK meritocracy had left behind. The poor were seen as a kind of inevitable underclass: not quite fully equal citizens, but a form of societal sludge.

The better-educated and better-off have had a tendency to close down discussions which, in all fairness, should have ended with the considered redistribution of national resources.

One example relates to immigration and housing. It is generally accepted that higher rates of net immigration place a greater strain on social housing supply. That’s not because foreign-born UK residents use social housing at any greater rate — foreign-born usage is roughly the same as that of UK-born people — but simply because a rapidly expanding population naturally requires more social housing provision, and construction rates haven’t kept up.

Not long ago, I watched an edition of BBC Question Time in which a man in the audience said something like: “I’m not racist, but with all these foreigners coming in my daughter can’t get a council house.” I knew that the immediate middle-class reaction to his blunt phrasing about “all these foreigners” would be to conclude that this man was indeed a racist or xenophobe, and dismiss his comments thereafter. And sometimes “I’m not racist, but…” is indeed a prelude to a racist remark.

But suppose policymakers took what the man said at face value? Suppose that, just as he said, he wasn’t a racist, but his experience was that high rates of net immigration — including that of some families categorised as at higher priority need — really did lessen his daughter’s chances of getting affordable, secure social housing?

The discussion wouldn’t have had to end up in resentment of foreigners. A better-functioning democracy, maybe one less imbued with class consciousness, might have actually listened. It might, perhaps, have concluded that — though freedom of movement brought significant benefits for UK citizens — lower-income groups were disproportionately likely to experience any negative effects of a rapidly expanding population.

To counter this, a succession of governments might have made it a clear priority to build social housing at a much higher rate, so that there was a better supply for all those who needed it. That way, UK-born people on lower incomes wouldn’t have been in competition with a growing number of foreign-born UK residents for a shrinking resource, for which 1.1 million households are now on the waiting list.

None of this national conversation happened, of course. The reason was that, for very many years, those in positions of power quite literally couldn’t find the common language for an honest, pragmatic discussion on sharply rising rates of immigration.

Socially and economically, I’m solidly in the metropolitan middle class. But I’ve absorbed enough lessons from my birthplace to understand the dangers of automatically dismissing and deriding people who don’t think exactly like you.

*

The decision to ‘Leave’ or ‘Remain’ is a genuine strategic and cultural disagreement — in this case on Britain’s long-term economic outlook, our government’s political accountability to the people, the nature of British and European identity, and our role within the wider world.

Despite our current flamboyant political chaos, there are arguments on both sides, neither of which require the automatic reduction of one to “traitors” and “enemies of the people” or the other to “morons” and “racists”. But tribal excitement is in the air.

I like Twitter, for its fast-moving coverage of politics and access to direct sources. For a time now, however, we have all seen the escalation of deeply nasty rhetoric, often from an angry, hard Leave perspective from outside the London sphere of influence — including anonymous, vicious threats to female MPs such as Anna Soubry, Diane Abbott and Jess Phillips. The UK is in a troubling place when judges are receiving death threats from Leave zealots and MPs require police protection from baying crowds on both sides.

Yet, increasingly, individuals with more prominent public voices, often on the Remain side, are joining in the nastiness, and delighting in crude insults or crafting ornately obscene insults for retweets and likes.

I’m not talking about passionate political disagreement, but statements that relish imputing the basest motives to those who think differently; people with whom, in any future version of the UK, the speaker will nonetheless have to share a country.

A couple of recent examples, among many — singled out only because they are freshest in the memory: firstly, the Guardian journalist Zoe Williams tweeting that the 76-year-old Labour MP Ronnie Campbell is a “scab” for deciding to vote for Boris Johnson’s withdrawal deal. (Campbell, incidentally, is an ex-miner who went down the pits at 14 and was on picket lines during the miner’s strike.)

Secondly, the writer John Niven tweeting a picture of his sweet-faced young daughter about to march in protest against Brexit (while carrying a large banner reading “Cock, Piss, Brexit”) — and attacking anyone who objected as a “gammon” and much worse.

I have lost count of the number of times reasonably well-known comedians, writers and commentators, incensed by the prospect of Britain leaving the EU, have called people they disagree with politically a “cunt” (although usually the word is embroidered with further eye-catching expletives to jazz it up). Each time, it brings me up a bit short. Maybe this feels to them like a swashbuckling expression of justified fury; they think it’s okay because they’re so sure they’re right. But then people on all sides think they’re right.

My political awakening involved a growing mistrust of tribal intensity, and a wariness of extreme rhetoric. To this I can now add a third element, contrary to what I might once have imagined — the realisation that England really isn’t so different from Northern Ireland, now that Brexit has given it a way to divide itself in two.

Be careful with the excitement, England, for those of you who are presently carried away with the thrill of belonging, the sudden exhilaration of full-throttle hating. After a while, you will become indistinguishable from your means, and your means will distort the ends. Believe me, it won’t be the first time that has happened.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe