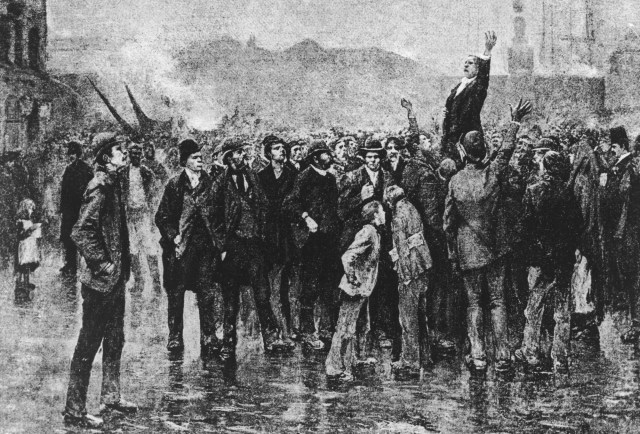

A labour leader addresses dockers during the London dock strike of 1889. Painting by Dudley Hardy. Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty

Throughout the unrest that has dogged our nation over the past three or so years, it is notable that our established church has been largely ineffective at facilitating anything approaching reconciliation.

Instead, the Church of England’s interventions over Brexit have been characterised by the kind of mild hysteria and hand-wringing that have, nowadays, become the stock in trade of that institution and its bishops. It seems to me that the Church, within its upper echelons at least, is now less the Tory party at prayer, and more a bunch of Guardian columnists at therapy.

Given that support for Brexit was always a fringe position among senior Anglican clergy, and that those bishops who have pronounced on it have usually done so only to bewail the spread of ‘hate’ and lecture us on how we must protect the poor from the consequences of their own votes, it is perhaps little wonder that those who voted Leave might be suspicious about the Church’s real motives. Thus, Justin Welby’s sermons calling for a rapprochement may resonate favourably in Remain-supporting Hampstead, less so in Leave-supporting Hartlepool.

All of this does, however, throw up the question of what constructive role, if any, our faith institutions might play in drawing together disparate and competing forces at a time of political instability.

Anyone searching for a blueprint could do worse than examine the momentous London dock strike of 1889, and in particular the part played by Cardinal Henry Edward Manning, then the 81-year-old Roman Catholic Archbishop of Westminster. This month marks the 130th anniversary of the conclusion of this most pivotal of industrial struggles – one whose roots lay in the grinding poverty and exploitation that were common features of the Victorian workplace.

Dockers of the age were treated as cattle, and subjected to the humiliating daily ritual of arriving at the dockside and being crammed into holding pens, compelled to jostle their way to the front in the hope of being hired for work. Often they were turned away, and would face the shame of tramping home to face their hungry families, before heading to the docks the next morning to try all over again.

It was an economic system at its most inhuman and degrading, filled with the type of indignity and personal anguish that was captured in that beautiful but heartrending 1948 Italian neorealist film Bicycle Thieves, in which the protagonist, a poor father, enlists the help of his young son in desperately searching around Rome – a city still ravaged by the effects of war and mass unemployment – for his stolen bicycle, a vital tool of his trade without which he cannot work nor feed his family. Returning desolate at the end of the day, he is unable to summon the courage to enter their home and face his wife, who is inside with their baby.

The London dock dispute, born out of a similar deprivation, centred on a demand for the “dockers’ tanner” – a rate of sixpence an hour – and a guaranteed minimum number of working hours. The strikes that were called in pursuit of these goals closed the entire Port of London, as around 100,000 men joined the protest. Solidarity flooded in. The Salvation Army fed the strikers and their families, and Australian waterfront workers sent donations. Jewish tailors in London’s East End, engaged in their own strike against sweatshop conditions, pledged their support to the dockers, and the dockers reciprocated.

For his part, Cardinal Manning, driven by his Catholic faith (he was a convert from Anglicanism), showed himself willing to incur the wrath of his fellow prelates by unashamedly taking up the dockers’ cause and becoming their advocate in negotiations with employers. He saw in the dockers a group of men who were downtrodden and oppressed. Their treatment conflicted with everything he stood for, principally the belief, central to his faith, that all humans were equal in the eyes of the Almighty and deserving of justice and compassion. Nothing about the dockers’ subjugation was pre-ordained as far as Manning was concerned.

He had form. In 1872, he had pledged support to the fledgling Agricultural Labourers’ Union, which landowners and farmers had tried to strangle at birth. And two years prior to the dock strike, he had intervened to prevent a papal condemnation of an early American union, the Knights of Labor.

But in spite of his overt support for the underdog, Manning commanded the respect of both sides in the dock strike and became a trusted mediator. He proved himself adept at reconciling opposing interests without ever sacrificing the support and trust of those with whom his heart really lay.

The dockers won their battle decisively. They got their tanner, and conditions improved. Manning’s portrait was carried by workers alongside that of Karl Marx at subsequent May Day celebrations. The dispute also gave a boost to the New Unionism of the time – a burgeoning of the trade union movement which saw the establishment of a number of unions representing thousands of unskilled and semi-skilled workers who until then had gone unorganised.

Manning’s efforts did not go unnoticed at the Vatican. Less than two years later, a ground-breaking encyclical – Rerum Novarum (Of the New Things) – was issued by Pope Leo XIII. The text, which was said to be influenced in no small part by the London dock strike, addressed the plight of the working-classes, stressing the need for justice in the workplace and warning of the deleterious effects of a predatory and unfettered capitalism.

As a means to countering vast wealth inequality – which he described as the “enormous fortunes of some few individuals and the utter poverty of the masses” – Pope Leo gave an explicit endorsement of the virtue of collective bargaining and supported the right to form trade unions. The message was that human beings were not commodities to be exploited by the rich: economic systems should be subordinated to the needs of man, not the other way round, and if they weren’t, then workers were justified in organising to defend their interests.

With its emphasis on reciprocity, relationships, the common good and the dignity of labour, Rerum Novarum can be seen as one of the foundation stones of modern Catholic social thought. It provided a crucial moral and economic framework for ensuring the representation of the voiceless in the face of a powerful, dehumanising market on the one hand, and an impersonal, over-mighty State on the other. Needless to say, Manning approved. Interpreting it later, he wrote: “A strike is like war. If for just cause a strike is right and inevitable, it is a healthful constraint imposed upon the despotism of capital. It is the only power in the hands of the working men.”

These questions remain as relevant today as they were in Victorian Britain, perhaps more so. In these times of rapacious globalisation, of transient and precarious employment, of the gig economy and zero-hours contracts, of the deracination of entire communities as a consequence of vast and rapid movements of capital and labour, of a widening gap between rich and poor, how might we return to first principles? How might we revisit the belief that respect for the dignity of humanity and labour are integral to the building of a common good, and that economic systems should be configured around the needs of man and – something that those who preach the gospel of liberal markets and liberal cosmopolitanism just don’t understand – his affinity for place and desire for belonging? Crucially, who will speak up for today’s working-class against an establishment that continues to ignore it and treat it with contempt?

In this age of aggressive secularism, do our faith institutions have any role to play at all in this debate? Are they even brave enough to enter into it? Experience tells us that the Roman Catholic church, with its tradition of fighting for social justice and its healthy disdain for fashionable opinion, stands as well-placed as any to do so.

Is it time for Rerum Novarum 2.0?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe