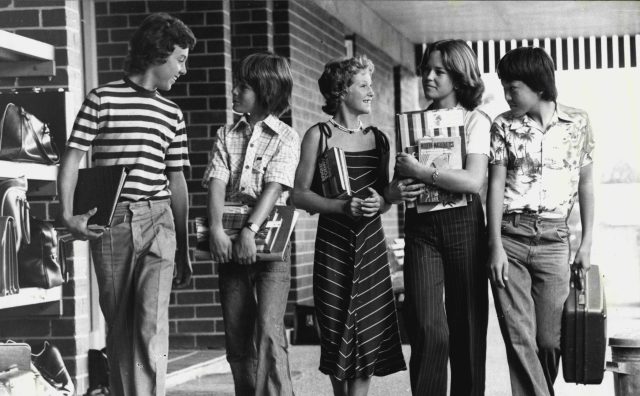

Students at a 1978 school that adopted a no uniform policy. Credit: Pearce/Fairfax Media via Getty Images

As children across the country head back to school, we asked our contributors to do the same. In this series, our writers share some lessons they learned at school – and how it shaped the way they think about education today.

I spent the sixth form in what was then a self-consciously radical comprehensive school in Milton Keynes. Stantonbury’s purported aim was to treat us like adults and to encourage us to believe we were part of an educational collective. The school was built, the teachers declaimed, on three Cs: Christian names, our own clothes, and carpets in every classroom. Once a month, on what was called Day 10, lessons were off and we did other activities, which we were supposed to initiate ourselves. Lower down the school, students – and we were all students not pupils – had hours each week of ‘Shared Time’, which was a strange hodgepodge of activities, with quite strong political undertones.

On my first day, I found my way to what a list on the wall said was my form class, only to be told that I wasn’t supposed to be there, because there was someone well established at the school who shared my name, and it was her class not mine. No-one, it seemed, knew I was starting, even though I had visited a few days before to meet the head of sixth form. By the afternoon, the form teacher had reluctantly accepted that she might have to accept me.

But then I discovered that one of the economics classes had been timetabled at the same time as subjects we had been informed, in the morning, that we could take alongside economics – because the economics teacher only wished to teach three lessons a week rather than the four offered for every other subject. What was supposed to be 12 teaching sessions a week was down to 10.

That day was, I think, the first time in my life that I acquired a palpable sense of what competence means. There was knowledge about how to organise practical things – at my old school in Nottingham, for instance – and there was an absence of it – embodied by Stantonbury. What I learned over the next two years was just what consequences could follow from this distinction that now loomed in my mind.

My friend’s geography class was entered for one exam board but taught another board’s very different syllabus. She worked harder than anyone I knew. She was the only person in the class who passed and her grade cost her a place at her first and reserve choice universities.

One history teacher regularly turned up seriously late, and then, when he finally arrived, set about dictating to us from a textbook we had all been given at the start of the year.

When the economics teacher left during the first term of the upper sixth, we had not started macro-economics, which was half the syllabus. The school could not find anyone inside the school willing to replace her, even though there was a teacher who could, and said the class wasn’t big enough to make it worth appointing a new teacher. Eventually, after weeks of being left largely to our own devices, they sent someone to our classes who we called our babysitter. By this time my friend Joe and I had bought a macro-economics textbook and were teaching ourselves.

Attempts to complain about these problems were met with at best indifference and at worst resentment. We were supposed to consider ourselves fortunate that we attended Stantonbury. To expect the school to be competent about timetabling, exam boards, or even teaching us at all when there was Shared Time to worry about, was implicitly deemed unreasonable and reactionary.

Yet Stantonbury’s idealism was not all hollow. My English teachers were brilliant. The two Pauls were the school’s ideals in action, and there were others like them. Without courting a cult of personality, they gave passionately of themselves in imparting their knowledge, and cultivated in us a desire and ability to think for ourselves. They taught us about the set novels, then expected us to go away and read the rest of the major work by those authors so we could come back with thoughts to discuss as their equals. Their classes were the most intellectually exhilarating educational experience I ever had.

When I left in the summer of 1985, I was more angered by the results carnage around me than grateful for what I had learned. I could in retrospect say that concentrating on what had gone wrong for others paradoxically represented an idealism that Stantonbury had, if not inculcated, probably sharpened. But it seemed more a simple matter of daily observation.

I knew my comprehensive school in Nottingham, for all its faults and with no ideological pretension about what it was doing, gave more to more children across the class spectrum than Stantonbury did or could. I also knew that where I lived many parents, for well-intentioned reasons, did not want to see how bad the worst of Stantonbury actually was. They wanted to believe, and I did not want my success to be another rationalisation for them, averting their eyes.

During the 1990s, Stantonbury turned away from its radicalism, although for a long time there was still no uniform and I presume the carpets remained in place. In large part, I thought the changes were the inevitable consequence of realities from which the school had run. I hoped it would let fewer people down.

Some part of me now looks back with sadness. I was better equipped for university education than the great majority of the students I now teach, because I had both been taught to think for myself and been forced to take responsibility for spending a lot of time learning by myself. A few years ago, I asked one of my first years – who I knew was struggling in ways I have come to recognise as common – whether “school felt a million miles away”. “No,” he instantly responded, “much farther than that.”

Yet I also cannot see the contrast as a vindication of the Stantonbury way. My student’s time at university eventually turned out well. Stantonbury, by contrast, would not have served him in the slightest. I have come to realise and accept that I am indebted both to the school’s ideals and the failures that dwarfed them. But I was fortunate; many of my schoolmates were not. And educational ideals should not yield such haphazard outcomes.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe