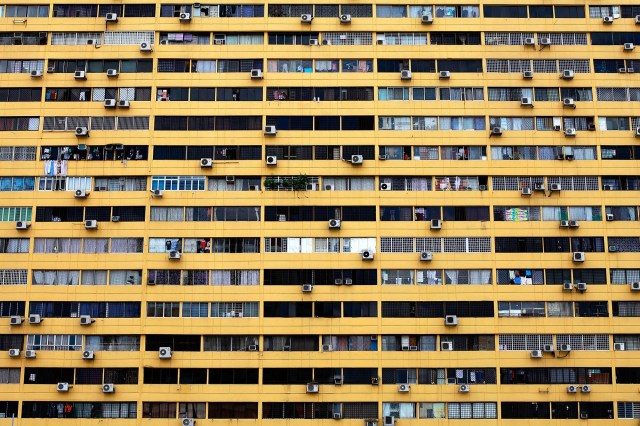

SINGAPORE – FEBRUARY 13: An exterior view of apartment flats in the Chinatown area. Credit: Nicky Loh/Getty Images

‘Singapore-on-Thames’ is shorthand for the fantasy of a hyper-capitalist post-Brexit Britain.

Whether dream or nightmare, it’s nonsense – not least because Singapore isn’t the laissez-faire haven it’s cracked up to be. Admittedly, it does possess some of the qualities that free marketeers hold dear – like comparatively low tax rates, but in other respects the Singaporean state is more interventionist than anything the UK is used to.

A good example is the island’s housing policy. It’s the subject of a thought-provoking piece by John Bryson for CityMetric:

“Singapore had its own ‘Brexit’ in 1965 when it separated from Malaysia. In 1960 the Singapore Housing and Development Board (HDB) was formed to provide affordable and high-quality housing for residents of this tiny city-state nation. Today, more than 80 per cent of Singapore’s 5.4m residents live in housing provided by the development board.

“These are issued by the state on 99-year leaseholds, and the value of the home depends on the inherent utility value of the property (size, type, location)…”

So Singaporeans own their homes – or at least the leasehold on their homes – but the state retains ultimate control over most of the housing stock. It uses that control to stop the island’s limited living space from being cornered by private landlords and speculators:

” … the development board prohibits Singaporeans from owning more than two residential units at any time. In the case of an inherited flat, ownership is only allowed if the inheritor disposes of their existing private or public residential property within six months of inheriting it.”

Singapore’s system doesn’t really fit into the categories we’re familiar with in Britain – it’s certainly very different from our open market in freehold and leasehold property, but it’s also nothing like the rented social housing as provided by councils and housing associations. It both encourages home ownership (the state even provides leasehold buyers with financing options), but discourages the exploitation of property as a financial asset.

This may appear to be more restrictive than, say, a pro-ownership policy like the UK’s Right to Buy, but it’s worth remembering that 40% of Right to Buy homes are now owned by private landlords – contributing to a serious decline in home ownership, especially among younger people. The Thatcherite dream of a deregulated economy and a property-owning democracy has been undone by its internal contradictions.

But could Singapore’s approach – a response to the city-state’s naturally limited land supply and hence the need for super-dense development – work in the UK?

London is a city-state, of a sort. The land supply is limited not so much by the size of the country, but by the planning system and by market demand for proximity to the city centre. Unlike Singapore, however, our capital city is full of private landlords extracting value from the productive economy.

Nevertheless, the state is still a major landowner in London – and controls large tracts of housing that could be redeveloped, densified and made available to the public along Singaporean lines. We just need a British version of the Housing and Development Board to make it happen.

Perhaps, we could ask the original version if they’d like to open a London branch. We have a Canadian Bank of England Governor, so why not pay for the services of Singapore’s world-renowned public administrators? I’m sure the British civil service, who tend to be liberal pro-immigration types, wouldn’t mind.

Certainly, we won’t tackle the housing crisis unless government beefs up its capacity to get stuck-in directly: buying-up land, getting stuff built and enabling ownership while blocking speculation. However, there’s another barrier to progress – politics.

Our leaders extol the virtues of home ownership, but still seem to think that rising property prices are a good thing too. In fact, it’s a form of inflation – and a glaringly obvious barrier to opportunity for anyone who isn’t yet a home owner. Yes, there’s a feel good factor if you’re already on the property ladder – but, beyond that, the benefit of rising prices is either purely notional (it won’t make your home any bigger) or, if you sell, comes at the expense of the buyer (who, by the way, will be you when you buy your next home).

It’s such a ridiculous mindset – and a political sensitive one. When I worked in Government, we could use language about making home ownership ‘affordable’, but not if it suggested an ambition to see property prices fall. That’s because, unlike in Singapore, we continue to regard our homes as money-spinning financial assets.

In America, Bernie Sanders – a self-described socialist and candidate for the Democratic nomination – unveiled his housing policy last week. A lot of it is pretty radical, featuring national rent controls and curbs on speculation. However, as Emily Badger notes in the New York Times, the Sanders campaign seems to be OK with the notion of housing as a financial asset as long as it is ordinary Americans who benefit:

“Mr. Sanders’s campaign… [argues] that rich investors or landlords shouldn’t get to make so much, while ordinary American families should have a chance to make something.

“’We want to return to the notion that homeownership can be an asset builder for working people and average American families, and it is not just a vehicle to commodify to make the rich richer,’ said Josh Orton, a senior adviser to the Sanders campaign and its national policy director.”

Are Sanders’ people suggesting that he wants to hold down property prices (with the rent controls etc ), but in other cases have them go up, so that non-wealthy homeowners can accumulate assets too?

A less contradictory interpretation is that buying a home as an “asset builder” simply refers to the equity one builds up by paying off the mortgage. I hope that’s what Team Bernie means, because the alternative of profiting from property inflation is to the detriment of people who don’t yet own their homes and perhaps never will.

In any case, it would be great if more politicians would stand up and state clearly that they don’t want our homes to appreciate in value. At the very least, they should aim for a future in which wages rise faster than property prices, not the other way round.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe