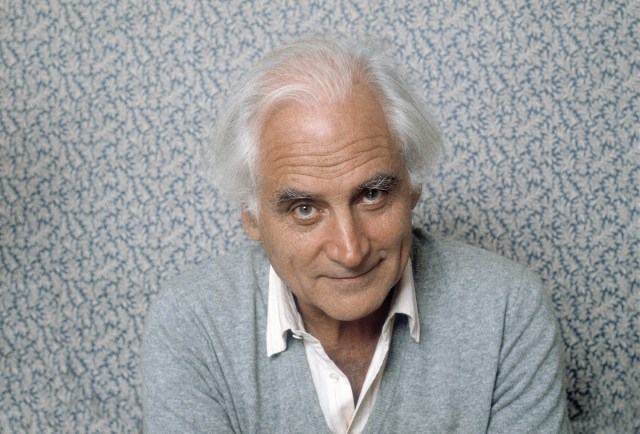

Michel Serres countered those who believed it was “better before”. Credit: Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Every summer, bookshops lay out stacks of blockbusters designed to be devoured in an afternoon and forgotten in a week. But at UnHerd we prefer books that leave a lasting impression. In this series of Summer Reads, our contributors recommend overlooked books that will engage and enrich you, not just distract you.

Michel Serres, France’s most popular, and most widely recognised, philosopher, was a kind of intellectual Johnny Hallyday.

If Hallyday was France’s “national rock-star”, Serres, a bargeman’s son, was France’s national thinker. Both men were similarly besieged with the adulation of their countrymen even though this was an age when French intellectuals were no longer lauded like pop stars.

Serres was unusual for a French philosopher – and unusual for a philosopher of any kind. He wrote best-selling books. He was a purveyor of hope. He adored the modern world. He was very amusing. He had a treasure-trove of anecdotes from his many lives as a naval officer, academic, mountain climber and TV star (of which we will presently hear one, involving President Charles de Gaulle and a giraffe).

Since he died in June, aged 88, two of Serres’ most recent books have re-entered the French bestseller’s list. One of them, La Petite Poucette, was translated into English in 2014 as Thumbelina: The Culture and Technology of Millennials.

The other, its 2017 sequel, c’était mieux avant! (everything used to be better), is currently available only in French.

The two books make overlapping arguments.

No, the world is not going to hell in a hand-basket. Young people are not separated from reality by their mobile phones. They are better informed and more engaged than any previous generation.

Democracy is not doomed. Au contraire, it is the old model of top-down, “tyrannical” or fake democracy, which will not survive the era of social media, Wikipedia and mobile phones.

Serres saw the gilets jaunes (yellow jacket) movement, which arose just before he died, as a symptom not of typical French grouchery but a sign of a new and welcome popular unwillingness to accept that the “big people” know best.

Long before Greta Thunberg, Michel Serres forecast that the young would save the planet. Unlike their parents or grandparents, he said, coming generations would no longer place the human race on a self-defeating pedestal above other forms of life. They would develop a “Natural Contract” (the title of another book written by Serres 20 years ago) which would re-establish human beings as partners, not destroyers, of other species, both animal and vegetable.

Here is a short passage from c’était mieux avant, which, though clumsily translated by me, captures something of the power of Michel Serres’ writing.

“This is the real law of the jungle – that you must at all costs avoid complete victory. Only mankind fails to grasp this point… As the day of our triumph approaches we will be forced to leave our pinnacle and reduce ourselves to the ranks of other living things if we want to survive… Quickly, quickly or we will die.”

Serres published more than 80 books. He was one of the 40 “immortals” of the Académie Française. He was trained in mathematical, scientific and literary-philosophical disciplines and tried to break down the popular and academic barriers between them.

He detested what he saw as lazy arguments about the dangers of modern communications, social media and the internet. As a son of the labouring classes and a child of the 1930s and 1940s, he hated suggestions that life had been “better before”.

When exactly was it “mieux avant”, his 2017 essay asks? When Hitler, Stalin and Pol Pot were murdering millions? When simple arguments about family and faith disguised widespread violence and sexual abuse? When women spent their lives in drudgery? When unthinking snobbery meant that his working class, south-western accent was mocked openly by his academic superiors and colleagues?

Mieux avant, a short book easily read by anyone with reasonable French, is a kind of socratic dialogue. “Grand Papa Ronchon” (Grumpy Granddad) defends the past. He is opposed, or educated, by Thumbelina, the millennial teenager from his previous bestseller, whose fast-moving thumbs can summon up a world of knowledge denied to her predecessors.

Mostly Serres agrees with Thumbelina. Occasionally he becomes Grumpy Granddad. He excoriates, for instance, the generic ugliness of the mall-sprawl on the edge of all French towns. In that case, he says, life was “better before”.

The two books have been criticised as too optimistic and simplistic – a 21st century reincarnation of Voltaire’s Dr Pangloss. “All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds”.

There are many contradictions and counter-arguments that Serres fails to address. He believes the “new dictators” – he lists Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Brexit and Isis – will ultimately be defeated by a new, engaged, well-informed, grassroots, internet democracy. He ignores the evidence that the internet has been exploited by Trump, Putin, Isis and others to impose a new autocracy, founded on fake news. He dodges the possibility that many Thumbelinas are not following world events on their iPhones.

All the same, Serres is a stimulating and refreshing antidote to the pervasive gloom of the age. He says that humanity, to survive, will have to learn to think small. He also believes that only bold and sweeping ideas can succeed.

The importance of thinking big is the point of one of his favourite anecdotes.

In the early 1960s, Serres was a teacher at France’s most elite academic institution, the Ecole Normale Supérieure, when the president of a newly liberated African colony visited President de Gaulle.

Two students at ‘Norm Sup’ stole a giraffe from the ménagerie in the Paris fifth arrondissement. They placed it in a truck and drove it to the Elysée Palace. Questioned by the police on the gate, they explained that it was a present to De Gaulle from the African leader.

To the subsequent fury of “le général” and his then prime minister, Georges Pompidou, the truck and the giraffe were allowed to enter the palace courtyard.

Serres saw two morals in the story. Humour justifies nearly everything. It is impossible to refuse something as big as a giraffe.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe