Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan. Credit: TOLGA AKMEN / AFP / Getty Images

John Cleese’s recent tweet about London – “not really an English city any more”– has been the subject of vigorous subsequent discussion.

Some years ago I opined that London was not really an English city any more

Since then, virtually all my friends from abroad have confirmed my observation

So there must be some truth in it…

I note also that London was the UK city that voted most strongly to remain in the EU

— John Cleese (@JohnCleese) May 29, 2019

Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London, amid the furore, tweeted his own view: “Londoners know that our diversity is our greatest strength. We are proudly the English capital, a European city and a global hub.”

So how English is London? Well that depends very much on what is meant by ‘English’. A significant problem with the word is that its ethnic and national meanings are often confused or blurred.

Ethnic groups, for instance, are large-scale communities which consider themselves to be descended from common ancestors, are attached to a particular ‘homeland’ and are distinguished from other ethnic groups by cultural markers such as religion, language or appearance. Nations, on the other hand, are territorial-historical communities with a degree of political aspiration. They are different things, though the same word is used to describe them.

‘English’ is both an ethnic and national designation. The English, for example, are the largest ethnic group in most of the more populated parts of English-speaking Canada, in the American state of Utah and in northern New England (see light purple shades on the linked map). They are also an overwhelming majority – around 70% – of the population of England. In London, however, they make up no more than 45% of the total.

Cleese, then, was right – if he was talking about ethnicity.

Equally, those of English national identity are also a majority in England, but not in London. Of England’s residents, 60% said they were ‘English Only’ in the 2011 census. In London, this was only 37%. This is because more than any other groups, ethnically English people also claim their national identity to be ‘English’.

And while ethnically English people tend to claim Englishness as a nationality, minorities lean towards a British identity.

Even though, according to the ONS Longitudinal Study (ONS LS), minorities under 30 are increasingly identifying as ‘English’, it is still accurate to claim that London is not an English-majority city in either ethnic or national terms.

But was it ever thus?

No. In fact, over the course of Cleese’s lifetime, there has been considerable change in London’s ethnic and national composition. While it’s true that London has always received immigration, this has typically been on a small scale. Jewish immigration, for example, was only about 5,000-10,000 per year at its height in the late 19th century.

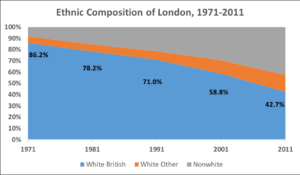

And while no ethnicity question on White Britishness was asked until 2001, we can use the ONS LS to track 2001 and 2011 London residents back to the 1971 census. This method finds that London was around 86% White British in 1971: an ethnically-English city with a modest minority. By 2011, the ethnic English were in the minority. These dates track the period from Monty Python’s debut to Cleese’s retirement. Living through that transformation no doubt influences his perspective.

Source: ONS LS 1971-2011

So, in these strict terms, it seems Cleese is on pretty solid ground in making his claim that London “isn’t an English city any more”. It is only English in the sense that it is located in England. But if we were to follow that to its conclusion, then all accents heard in London must be English ones, which would be an absurd thing to say.

Can we, therefore, dismiss Cleese’s critics as overreacting? Well, not necessarily.

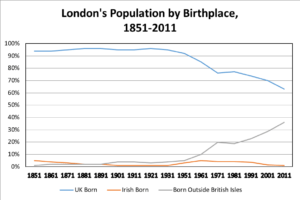

There is nuance to this story. There is a sense in which London is still English: the majority of its population is native-born. The UK-born (nearly all English-born) formed nearly 80% of the city into the 1980s, and while this had dipped to 60% by 2011, natives remain a majority.

Source: Hechter, M. (1976). UK County Data 1851-1966 (UKDA ref#430); Census of England and Wales 1971-2011.

Is being born in England enough to qualify as being English? Yes, say 85% of those asked in the BBC-YouGov 2018 Englishness survey. On this logic, London is still an English city, but if it passes the 50% foreign-born mark – like Miami, Dubai or (almost) Toronto – then it would cease to be so.

But even though London may still be (marginally) English by birth, if its inhabitants think of their ethnicity and nationhood in non-English terms, then Cleese’s point stands.

But what if there are people – notably ethnic minorities or white liberals who claim to be British rather than English – who have an English national identity but who don’t explicitly acknowledge it? As Daniel Kahneman writes, people “aren’t rational, they rationalise”. Their subconscious impulses drive them, but the deliberative part of their brain constructs a story about why they behave as they do – which often bears little relationship to the underlying motivations.

If this is the case, then a good test of what nationality ‘British not English’ Londoners hold deep down would be to see if they back the English football team, or feel defensive about the anti-English barbs levelled by relatives in Wales or Scotland, or care when they hear that Scotland gets more out of the Treasury than England. If they do, they quite possibly do have an English national identity. Though because they imagine a white, traditional Englishness, rather than the more modern version, they consciously reject it. On this measure there are only a few Londoners who aren’t English – unconsciously or otherwise.

It’s possible these Londoners also have English symbolic attachments. When people, regardless of whether they identify as English or not, were asked in the same Englishness survey how strongly England’s ‘diverse cultural life’ contributes to ‘your English identity’, for instance, 75% of non-white Londoners replied ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ strongly. This is also true for 73% of White British Remain-voting Londoners, though only 45% of Leave-voting White British Londoners concur.

When it comes to the English landscape, things veer the other way: this is important for 85% of White British Leavers in London, 73% of White British Remainers but just 54% of non-white Londoners. There is nearly as great a divide on the importance of English ‘history and heritage,’ with almost 90% of White British Leavers in London saying this is important for their English identity against 77% of White British Remainers and 63% for minority Londoners.

But while minorities are not quite as keen on landscape and history, a majority still consider these to be an important part of English identity. And on English sport, Christian traditions, poetry and dance, there are only small differences between white Londoners and non-white Londoners. If these people really didn’t identify as English, would they still reply that these symbols were important to ‘their English identity’? It seems that when you probe a little, many who claim not to be English are significantly attached to its key symbols.

So where does this leave Cleese? For conservative whites, such as Cleese, English ethnicity blurs into their concept of nationhood. Being ethnically English makes it more likely that they will identify their nationhood as English which, in turn, shapes the symbols (landscape, history) that make up the image of England in their head. Ethnicity is the lens through which they view the nation; it seems inseparable from their national attachment.

When confronted by an ethnic minority person, therefore, who possesses English characteristics (attitudes to sport and Scotland, say) Cleese’s reflex may be to consider such a person not ‘truly’ English. Not because he wishes to exclude minorities from the nation, but because he has no vocabulary for distinguishing his ethnic identity from his national one.

I’m not convinced Cleese has a sinister desire to exclude minorities from national membership. I can’t know for sure, but, as an expat living in the Caribbean, he may simply wish to express his diaspora English ethnicity, as well as his attachment to an England in which his group forms a majority, but not the entirety of a nation in which minorities are equal members.

In my book Whiteshift, I call this ‘ethno-traditional’ nationalism, as distinct from exclusivist ethnic nationalism, which seeks to limit national membership to members of the ethnic majority while repatriating, or discriminating against, minorities.

Meanwhile, as John Denham argues, Englishness is becoming more inclusive. Ideally, English national identity would be what I call multivocalist, a kind of Englishness-as-menu which would permit some to attach to England through the nation’s landscape, ancestry and history, while others can relate to its ‘diverse cultural life’, sports, vibrant economy or popular music.

So Cleese should allow that the ethnic English no longer have a monopoly on English nationhood; native-born minorities are just as English, but imagine their nation differently. Equally, Sadiq should allow that Cleese has a right to identify with his English ethnicity, and to cherish his own conception of London – and England – as opposed to the cosmopolitan one promoted by the mayor’s office.

London has become less English since Monty Python premiered, and is no longer ethnically English. But a majority of its residents are English-born and most identify with some version of English national identity. So is London still an English city? Well that, of course, depends what you mean by English.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe