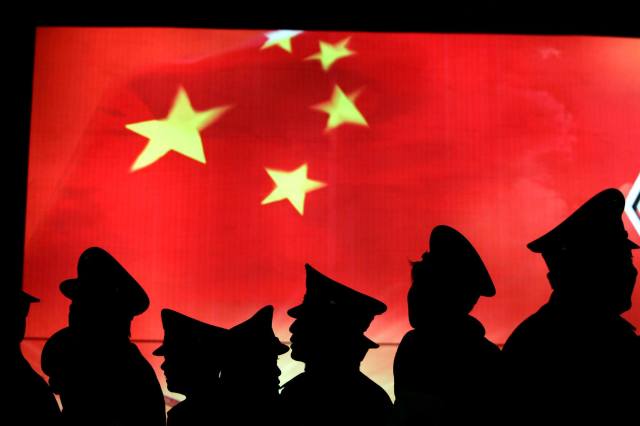

Credit: China Photos / Getty

The Cold War that ended 30 years ago was an ideological battle between capitalist democracy and totalitarian communism. Now the geopolitical struggle is civilisational and it pits Western humanism against the anti-humanist outlook of China’s ruling classes. The West is unprepared because its elites fail to understand the nature of the threat.

Most Western liberals view growing tensions with China only in economic terms. They lament the intensifying trade war waged by the Trump Administration and still believe that more globalisation will somehow integrate China into the liberal world order. For them, history really did end in 1989, when they expected a global convergence towards Western market democracy.

The surprise about setbacks – from Iraq in 2003 to the 2008 financial crisis – has since morphed into a state of denial. Brexit, Donald Trump, and China’s assertion of sovereignty over the South China Sea are misunderstood as just headwinds that will not blow the ship of liberal globalisation off course for long. For liberals, low wages, deindustrialisation, and job-exporting trade deals are seen as inevitable in the forward march of progress, when, in reality, this programme favours China at the expense of the West.

Worse, liberals do not grasp that China’s fusion of Leninist state collectivism with totalitarian tech control represents a threat to Western civilisational norms, notably a commitment to the dignity of the person enshrined in fundamental freedoms, rights, and mutual obligations.

It is not just that Beijing views political liberalism as a source of weakness and corrosion of its hard-won authority. The Chinese leadership also rejects the principles of liberality on which Western civilisation depends, such as free inquiry, free speech, tolerance for dissent, respect for political opponents, freedom of religion, and the fair treatment of minorities.

The West needs to do much better to live up to its own ideals; but contemporary China is fast becoming a totalitarian system under a new guise. This includes a crackdown on domestic opposition, the internment of up to a million of Uighur Muslims in the restive region of Xinjiang, as well as the persecution of Christians and other religious groups across the country.

What is new is a surveillance state that manipulates minds and creates a climate of fear and self-censorship, combined with the aggressive promotion of Chinese ownership of key strategic assets as part of the Belt and Road initiative of infrastructure investment. Neo-Confucian ‘global harmony’ and China’s supposedly peaceful rise are a cipher for the country’s hegemonic ambitions.

Few, if any, Western governments have taken a stand. But if the West does not speak up for the persecuted Muslim minorities in China, and for the freedoms of all the Chinese, then Western values mean nothing.

The US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo seems to recognise this when sounding the alarm about worldwide Chinese influence. During his visit to London last week, he criticised Theresa May’s government for allowing the Chinese company, Huawei, to participate in Britain’s new 5G mobile phone network. The threat exceeds, by far, the potential theft of intellectual property and even national security. It is about the control of technology that is capable of redefining what we mean by freedom of conscience and free speech.

“I think we have to take the rose-colored glasses off and get real about the nature of the threat,” Kiron Skinner, the director of policy planning at the US State Department, said last week at a security conference in Washington. “This is a fight with a really different civilization.”

Skinner’s intervention matters because of the key position she holds within US foreign policy-making. Her office is responsible for developing US grand strategy. It was from this office that 60 years ago the US diplomat George Kennan implemented the policy of containment to counter Soviet expansion.

Skinner’s remarks about the civilisational nature of Chinese power have caused a major uproar. She has been accused of racism, for calling China the first “non-Caucasian” power to threaten the USA – even though she is one of the few senior US policy-makers who is African-American. The choice of words was perhaps unfortunate, since imperial Japan was arguably the first non-Western country to defy the West. But blunt language is needed to wake up a sleepy elite. Skinner is right that Beijing poses a unique challenge because it is not part of the tradition of Western philosophy, history, and culture, and she deserves credit for calling this out.

Her language has also invited comparisons with the idea by the American academic Samuel Huntington about a “clash of civilizations“, which suggested that after the end of the Cold War, conflicts would be predominantly between civilisational traditions rather than ideological systems. But Skinner does not say that the battle between the West and the rest is inevitable, as Huntington (or rather a simplistic reading of him) implies. Instead, she maintains that “we also have to give a kind of respect for what the Chinese seek to accomplish”.

She’s right, though, about rival civilisational norms. The West is committed to the intrinsic worth of each and every person. Contemporary China, by contrast, is concerned with the collectivity. The West believes in personal rights and obligations set out in constitutions that constrain state power. China, on the contrary, believes in obedience to an omnipotent state that overrides constitutional boundaries.

The West promotes a market economy based on private ownership and free enterprise. China is building a model of state capitalism based on Communist control of property and state-owned corporations. The West seeks to uphold a free space of human association independently of the state, whereas China views all intermediary institutions as a conveyor belt between the party and the people. This fundamentally different outlook is at the heart of growing tensions between the West and China.

Western concerns with the dignity of the human person enshrined in human rights rest on Christian humanism and its focus on the common good. This is not a collective ‘public good’ imposed by experts, but rather a good pursued by all, which exists only in reciprocal relationships and the constant striving towards both individual fulfilment and mutual flourishing. The liberty of each and the equality of all are important principles, but even more important is lived fraternity. It redeems freedom devoid of social solidarity and provides trust and cooperation. What binds people together is what makes us free and society more just.

By contrast, the Chinese leadership defines harmony in terms of collective utility – the greatest happiness of the greatest numbers. This is brought about by the central state and enlightened elites who have been carefully selected to enforce the will of both party and army. China’s ruling Communists are deploying high-tech facial recognition and algorithms to control individual behaviour. The system of social credits rewards obedience and compliance. The fusion of a Leninist ‘administration of things’ with neo-Confucian collectivism replaces the Western idea of a government of the people with a tyranny by numbers. All this – combined with large-scale Chinese investment in Artificial Intelligence, robotics and genetics – suggests that Beijing is more interested in the power of the strong over the weak than the equal dignity of all.

Against this background, Skinner’s warning is one the West should heed. If China continues to deny its citizens religious freedom and the right of political dissidents to emigrate, then Western countries have a duty to act.

Skinner is leading work to develop a concept of US-China relations on the scale of Letter X, the seminal essay by Kennan that laid the foundations for Western containment policy against the Soviet Union. Such an effort is now required to be clear about the threat posed by China but also about the potential to bring about a proper balance of power anchored in respect between different civilisations.

The West needs to develop a strategy of how to confront China in the case of human rights abuses, while at the same time encouraging the country to renew the legacy of Confucian and Buddhist social virtues, such as hospitality, benevolence, and trustworthiness. The damage of Mao’s Cultural Revolution needs to be repaired and not plastered over by Xi Jinping’s increasingly atavistic nationalism.

But the West also has to uphold its own best traditions and practice the principles it inherited from Greco-Roman philosophy and law as well as Judeo-Christian religion and ethics – the unique value of the person and free human association independent of the state, which are under threat everywhere.

Above all, what is missing is meaningful dialogue between civilisations for the benefit of mutual understanding and cooperation based on shared interests. A ‘clash of civilisations’ is neither necessary nor normative.

When the Iron Curtain fell 30 years ago, Vaclav Havel – the Czech dissident turned President – said that “we are concerned for the destiny and the values that brought down Communism – the values of Western civilisation”. Havel was right. The renewal of Western civilisational norms is vital for the West and the world.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe