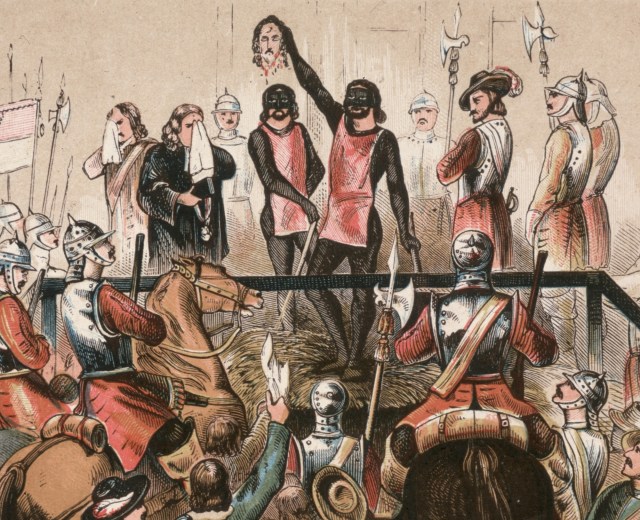

Head of State: the severed head of King Charles I in 1649. Credit: Hulton Archive / Getty

It was 6 January 1641: in the Guildhall tradesmen gathered, shouting “Parliament, Privileges of Parliament”. Why should ordinary London apprentices and tradesmen have cared about Parliament? They didn’t even have the vote because most of them weren’t rich enough.

The reason was simple: they understood that Parliament was trying its best to check the swelling power of an over-mighty executive that was ignoring not only Parliament and the gentleman who sat in it, but the ordinary people in the street as well.

In 1641, that overmighty executive was the monarch, Charles I, and his court, a court that included the Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, who had imposed very unpopular reforms on a reluctant Church of England with the king’s support.

Ecclesiastical reform doesn’t make the political pulse race in 2019. Perhaps Brexit will be as incomprehensible to our great-grandchildren. But the nation was as passionately and bitterly divided over religion as it now is over the European Union. This was not only a matter of faith; it was also a matter of identity.

Like some members of the current executive, Charles I claimed that his position was the traditional one, that he was defending the Church of England and the historical constitution of the three kingdoms. Parliament was deemed an obstacle because it wouldn’t give him his own way. Parliament, though, was simply doing its job of reviewing legislation and restraining recklessness.

Charles reacted to Parliament’s criticisms by refusing to summon it and trying to rule the country alone – the personal rule, something of a figleaf term to cover what was really a power grab by an absolutist monarch – a policy that led him into increasingly unjust and resented taxation policies that directly affected the gentleman landowners who made up the vast majority of members of Parliament. And for which he paid dear.

This complex history illustrates the sophistication of the Westminster system. Like all successful democratic systems, the Westminster system is dependent on a series of checks and balances. Central to these is Parliament’s role in reviewing the legislation put before it by the executive – currently the Prime Minister and Cabinet, previously the monarch. In such reviews, it acts as representative of constituencies, well understood as having diverse and sometimes conflicting interests.

The Westminster system was brutally revised by the shooting war that followed. Ironically, the king’s power grab led to the rule of half the country directly by Parliament, and that in turn led people who were willing to die to defend the principle of parliamentary sovereignty to ask whether that sovereignty itself needed some examination and improvement.

This in turn led to one of the most important events in English history, the Putney House debates. These were a series of discussions within the Army held on 28 October 1647 concerning the make-up of a new and more just system of government for England.

The name of Colonel Thomas Rainborough is not well known, but it was he who took up the theme of why ordinary men without a vote had shed their blood for Parliament: “I would fain know what the soldier hath fought for all this while? He hath fought to enslave himself, to give power to men of riches, men of estates, to make him a perpetual slave.” The army commander and Oliver Cromwell’s son-in-law Henry Ireton responded as follows:

“I will tell you what the soldier of the kingdom hath fought for. First, the danger that we stood in was that one’s man’s will must be a law…”

But Rainborough replied:

“Really I think the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest he; and therefore, truly sir, I think it’s clear that every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government, and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under.”

This is a ringing endorsement of franchise independent of property, and an illustration of the way Parliamentary democracy was believed to work at the time when people were willing to die for it. The individual voter, by voting in parliamentary elections, ceded sovereignty to their Member of Parliament to act on their behalf, voluntarily putting themselves under the government.

To overturn this today, by claiming that the 2016 referendum returned the favour by ceding parliamentary sovereignty to the voters is a dangerous fiction. It is a fiction because the legislation said no such thing; it is dangerous because it threatens to overturn the Westminster system in favour of the rule of an overmighty executive claiming to be acting on the people’s behalf.

Presumably, Theresa May is not planning to raise her standard in Nottingham; she’s learned that much from history. But she has raised her standard for acting outside the Westminster system in the interests of those who voted Leave. To complicate matters, though, more than six million people have signed a petition demanding that the Government revoke article 50, and hundreds of thousands marched in central London for a second referendum. The Government, though, claims this does not compromise its efforts to represent “the people” against Parliament.

It is and always has been entirely open to the people to petition Parliament, as well as to lobby their MPs, and they did so frequently during the English Civil War. The most famous petitioners were women; first came the women’s peace protesters, followed by the Leveller women. On both occasions, they were derided by their opponents as whores who had been inveigled by men.

A group of women wearing white ribbons gathered outside the House of Commons in August 1643 to demand that Parliament make peace with the King, presenting the house formally with a signed petition. One newspaper called them “whores, bawds… beggar women and the very scum of the suburbs, besides a number of Irish women.” (Those damned foreigners.) Parliament paid them no real attention, in part because it believed that they had been organised by a conspiracy of royalists or Catholics or Irish Catholics; conspiracy thinking was rife during the period. They were sent home, to ‘meddle’ with their ‘huswifery’.

It was the same story with the Leveller women’s petition. In April 1649 a group of them declared:

“That we have an equal share and interest with men in the common-wealth, and it cannot be laid waste (as now it is) and not we be the greatest & most helpless sufferers therein.”

They also demanded the release of the recently arrested authors of a pamphlet that supported universal male suffrage.

Despite efforts to connect women’s protests with the idea of “the world turned upside down”, petitions like this were highly conventional. Usually, women whose husbands had been imprisoned and especially those whose relatives had been condemned to death would address their petitions to the monarch; with Charles’s authority in abeyance, these women addressed their grievances to the Commons.

Petitioners have brought great changes, not by terrifying or threatening MPs, but by peaceful mass demonstrations. Such petitions are the usual way for people under the Westminster system to make it clear that in their minds, the government is in danger of betraying their trust. Governments that take no notice usually face a backlash, as both the Long Parliament and Charles I can attest.

When it came to a shooting war, one Civil War battle was amusingly characterised by both sides having the same war cry: “God with us!” In the same way, all sides in the Brexit debate claim to be trying to save democracy. All sides claim to be representing the will of the people. The problem is that the nation is now so deeply divided – and not in ways that can be represented by the division in the Commons into two parties, government and opposition – that claims to “represent the people” leave other people feeling unrepresented.

This illustrates the failings of populism; anyone can claim that they have the will of the people behind them. MPs, however, are supposed to be willing to put aside the interest of party – and let’s recall that parties came relatively late to the Westminster system and were themselves the result of a particular political crisis over Charles II’s successor – in order to arrive at the best decision for the country.

In his history of his own times, far better known to 17th-century MPs than it is now, the fourth century BC writer Xenophon tells the story of the way the democracy condemned military commanders in the Navy who had successfully defeated a Spartan fleet, but had not returned to pick up survivors of the battle. He says the crowd in the assembly was whipped up to a fury by one of the rowers who had survived the battle. A few brave people spoke against condemning the admirals to death, but then, Xenophon says, a shout went up “that it was intolerable for the people not to be given what they wanted”. The admirals are duly executed en masse. After Athens is conquered by Sparta, the mass trial is used as a precedent by the 30 tyrants for further mass executions.

Brexit seems to some like justice, others like democracy in action in its purest form. What our 17th-century ancestors knew much better than us is that populism invariably opens the door to tyranny in the long- and medium-term, however good the justification for its inauguration. The Westminster system, like every other long-lasting modern democracy was built to prevent tyranny. We are now in danger of opening the door to it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe