Timothy Richard was once the most famous westerner in China. His bearded profile still graces museums in the People’s Republic, his statue stands in the grounds of Shanxi University – which he co-founded – and even the Communist Party honours him as the first person to mention Marx and Engels in Chinese.

One hundred years after his death, he is largely forgotten in Britain. But modern China still bears the imprint of his works. Today, our image of the missionary is a colonial caricature. But Timothy Richard was no “white saviour”: he played a critical and intellectual role in China’s political development.

Shortly before he died, on 17 April 1919, Richard received a special visitor. Liang Qichao, modern China’s first ‘public intellectual’, made a pilgrimage to his small house in the London suburb of Golders Green. Liang was en route to the Versailles peace conference to lobby on behalf of the new Republic of China. Why was this leading reformer, the father of Chinese journalism and the founder of Chinese modern history-writing, so keen to meet a 75-year-old former Baptist missionary?

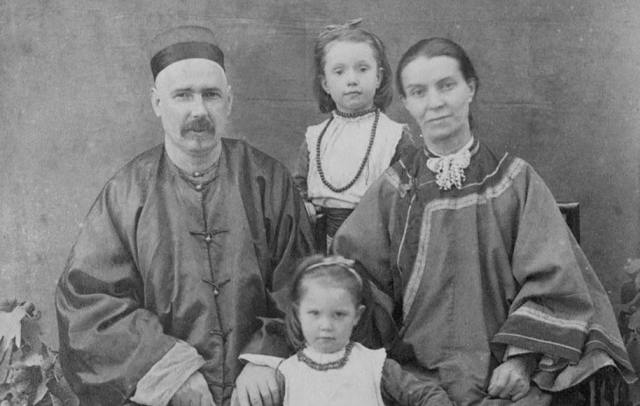

The story begins in 1845, in Ffaldybrenin, a one-chapel village in the Camarthenshire hills. At the age of 24, Richard enrolled in Haverfordwest theological college. China became his vocation. After four years of study and a three-month journey by ship, he arrived in Shanghai, on 12 February 1870. The Baptist Missionary Society sent him north, to Qufu in Shandong province, where he lived among the people, wore local clothes and learnt Chinese. He married another missionary, Mary Martin, in 1878 and they had four children.

From 1876-79, northern China was struck by famine. At least ten million people died in the provinces surrounding Beijing. Appalled at the incompetent response from local officials, Richard and Martin set up their own relief effort and mobilised their Christian supporters in Britain. The resulting China Famine Relief Fund, founded in Shanghai in January 1878, became, in effect, the first international aid organisation.

More importantly, according to Richard Bohr, who in 1972 wrote a book on Richard’s role during the famine, “Richard emerged from the calamity convinced that he must urge China’s leaders to eradicate the basic causes of famine and similar natural disasters and to elevate the physical as well as the spiritual welfare of the rural masses.” The sight of mass death awoke a political as well as a spiritual mission within him.

In 1891 Richard was appointed Secretary of the Society for the Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge Among the Chinese (SDK – also known as the Christian Literature Society for China – CLS), whose purpose was to translate and circulate materials “based on Christian principles”.

It was society’s firm belief that their mission was not just religious but social: “pure Christianity, as a matter of fact, has lifted up every nation that has thoroughly adopted it”, as they put it in their annual report of 1898. They were preaching the gospel of westernisation just as much as the gospel of Christ. The society’s explicit strategy was to reach out to “the future rulers of China” and they found a receptive audience among a section of the elite.

Another of the SDK’s tactics was to publish the Wanguo gongbao, a Chinese-language magazine carrying a mixture of Christian argument, articles about European progress and calls for political reform; many of them written or translated by Richard. The newspaper caused such a sensation that the leading reformer, a scholar called Kang Youwei, set up his own version with exactly the same name.

In October 1895, Kang and his young disciple, Liang Qichao, went to meet Richard. The two found common cause immediately. Liang became Richard’s secretary for several months. Richard became a founder member of Kang’s reformist “pressure group” the Qiang Xue Huior “Strengthening Study Society”.

While working as Richard’s secretary, Liang compiled and published a bibliography of key texts that his fellow reformists needed to read. It included the society’s Wanguo gongbao newspaper and many European works translated by Richard. Notable among them was a popular history book, Robert Mackenzie’s The Nineteenth Century, which went on to sell more than a million copies in its Chinese translation – and had a profound impact on the way Chinese history is written to this day.

In 1898, Kang and colleagues persuaded the emperor to announce major reforms. However, just over 100 days later, the emperor’s aunt, the dowager Empress Cixi, launched a palace coup. Richard was due to meet the emperor on the day of the coup but appears to have been forewarned. Instead, he and other members of the society helped spirit the reformist leaders out of the country. Both Kang and Liang made it to Japan but six of their colleagues were executed.

In exile, Kang and, particularly Liang, continued to be prolific writers and agitators. Their ideas had a profound effect on both the reformers and then the revolutionaries who overthrew the empire in 1911. Liang was appointed to successive government positions, from where he continued to argue for liberal social change. In 1913, he and Kang were reunited with Richard in Beijing. Liang took the opportunity to expound his views on how to write Chinese national history – views directly influenced by Richard and his translations.

Richard left China for the final time in 1916. Suffering from poor health, he had resigned his position as secretary of the SDK at a meeting in Shanghai the year before. A motion of thanks was formally agreed, noting that Richard’s name had become a “household word in China”. It would take the First World War to bring Richard and Liang back together.

Shortly after the signing of the armistice in November 1918, the victorious powers announced the convening of an international peace conference in Paris. A new world was in prospect: one where peace and justice would prevail and the rights of new nations would be respected. Although not a member of the government, Liang Qichao resolved to lead a personal mission to the conference.

Their ship docked in London. Of all the people whom Liang wanted to meet in the city, the first was Timothy Richard. Despite his ill health, Richard was still active: lobbying the great and good in support of a new organisation that would preserve global peace: a League of Nations.

Richard and Liang were confident that a new world was in prospect. In honour of the two men’s friendship, Liang presented Richard with ten volumes of his writings, the fruit of a journalistic and political career that had been sparked by their meeting in Beijing a quarter-century earlier and went on to shape the China we know today.

Bill Hayton’s book, ‘The Invention of China’, will be published by Yale University Press in 2020

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe