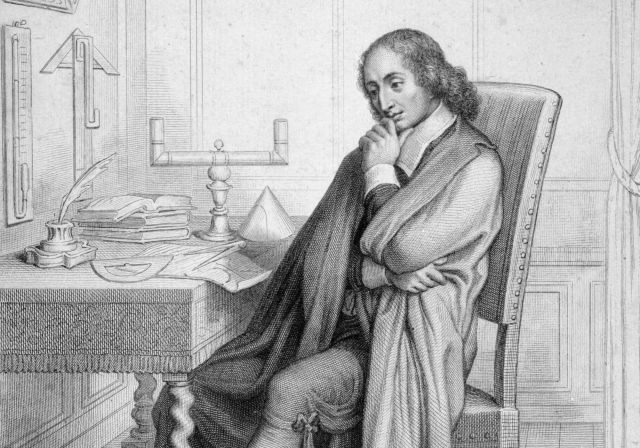

(Photo by Three Lions/Getty Images)

Pascal’s Wager is well known. If God doesn’t exist, so the argument supposedly goes, then if you believe, you haven’t lost that much (just forgoing a few minor pleasures or luxuries in this life). If, however, God does exist and you don’t believe, you not only miss out on the joys of life with God in this life, and eternal life in the next, but also risk an eternity of suffering in hell. Hence, it’s better to be a Christian.

Although it has some defenders, the argument has, over the years, been slated on a number of grounds. Critics include Voltaire and Diderot, nearer to Pascal’s own time, to more recent thinkers such as Nassim Nicholas Taleb, whose book Skin in the Game was cited by Giles Fraser in a recent article. Some argue that even if it works, it doesn’t answer the question of which religion to follow. Others, like Taleb, say it encourages the wrong kind of belief – faith without commitment, with no “skin in the game”. In short, it fails to be a persuasive proof of the need for faith.

The only problem is that Pascal never meant it to be that.

Most of its detractors (and many of its defenders) make a very common mistake. They take it as an attempt by Pascal to convince unbelievers of the benefits of faith. But it isn’t.

As with any text, the Wager needs to be understood in the context of the work as a whole, as well as the fairly long section in which it is laid out. Blaise Pascal was a mathematician and physicist working at the cutting edge of scientific questions in his own age. He was also a deeply religious thinker. The Pensées were the notes Pascal made towards a book addressed to a very particular audience – a work that was never finished due to his early death.

Many think he had in mind the sophisticated “cultured despisers of religion” in France in the 17th century. Pascal knew many such libertins, who enjoyed philosophising, drinking and gambling. When he was younger and less religious, such friends would urge him to use his mathematical genius to work out the odds on bets they were thinking of taking on. Many of them were influenced by the hugely popular philosophy of Pascal’s older contemporary, René Descartes, thoroughly convinced of the power of human reason to master the world; some had gone beyond Descartes to argue that Christianity was illogical and therefore no rational person could believe it.

Pascal’s beef with Descartes was that he didn’t understand people. Descartes’ idea of the thinking self (“I think therefore I am”) suggested that humans were entirely rational beings, motivated by and capable of cool level-headedness, making decisions on strictly logical grounds. Pascal thought this was nonsense. For him, our anxieties and desires are more powerful than our rationality. As he puts it in one vivid image:

“Put the world’s greatest philosopher on a plank that is wider than need be; if there is a precipice below, although his reason may convince him that he is safe, his imagination will prevail.”

Our fears and emotions are more powerful than our rationality, our longings more influential than our logic.

So when it comes to the Wager, the whole piece is designed not to persuade these sophisticates to believe, but to reveal the reasons why they don’t believe. The argument really runs like this: “The wager on belief is a bet you have to make – you can’t choose not to – either God is real or he isn’t. And you say that you don’t believe on strictly rational grounds, but do you really? You like a bet, right? OK, then look at the odds on belief. If you bet on God not existing, you don’t actually risk losing much. But if you bet on God existing, you stand to gain a huge dividend.

So looking objectively and rationally at the odds on offer here, a betting man or woman would always bet on belief. But we both know that you don’t. Why? It’s not because you are being rational: it’s because belief is inconvenient; you would rather there was no God; it costs too much, and you just don’t want to believe.”

As Pascal puts it at the conclusion of this section of the Pensées: “At least get it into your head, that if you are unable to believe, it is because of your passions, since reason impels you to believe and yet you cannot do so.”

It’s not that reason has no place – in fact Pascal argues that to exclude reason altogether is as big a mistake as to think that it is only reason that dictates our decisions. Yet only when we realise how it is our desires that influence what we choose to believe can we begin to make progress.

The Wager was never meant as a cold, logical argument for belief in God. It is, in fact, the opposite: an argument designed to show that we are not the purely logical, rational beings we sometimes think we are.

For Pascal, God cannot be known simply in our minds, as the conclusion of a cogent philosophical argument, but by the heart and soul: “It is the heart that perceives God, and not our reason.” If, then, we are caught between our logic and our desires, how do we get out of this dilemma? For Pascal it is only by making the first step – by taking the risk, not of abstract belief, but of costly commitment: as he puts it “You want to be cured of unbelief? Become like one of those who now wager all they have … They behaved just as if they did believe.” For Pascal, there is no such thing as cost-free faith. Faith means sacrifice. The way to salvation is, in fact, only found by having skin in the game.

These days, the drinking and the gambling are still as prevalent as ever (just watch any advert at half time while watching sport on TV). When it comes to philosophising about God and belief, we are more likely to be influenced by Richard Dawkins than by Descartes. Those who follow that path tend to claim on strictly rationalistic grounds that science and faith cannot live together, that reason rules out religion.

Yet Pascal and his Wager remind us not only of the compatibility of scientific exploration alongside religious faith within an extraordinarily fertile mind but also that we are more complex than the rationalists would have us believe. Pascal’s Wager does not try to prove Christianity, or indeed any religion.

What it does tell us is that when deciding on the deepest questions of life and existence, we need to be mindful not just of our logic, but of whether we are simply convincing ourselves of what we would quite like to be true. As Pascal himself says: “The heart has its reasons of which reason knows nothing.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe