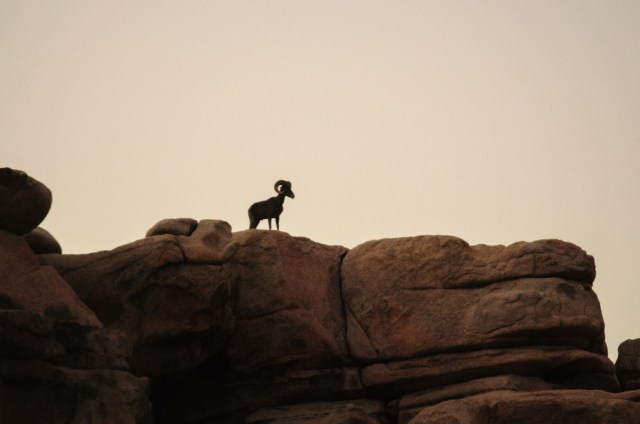

Credit: Getty

Ignore science and you ignore many of the most important issues in the world today. Climate change, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence – the relevance of all of those should be obvious.

Less so the travails of the bighorn sheep – the subject of a piece in the Atlantic by the brilliant Ed Yong. What, at first sight, looks like a bog-standard conservation story, is really quite extraordinary.

The bighorn is a native North American species that suffered a similar fate to the American bison. By 1900, hunting and other human interventions had reduced its numbers from millions to the low thousands.

In more recent decades, the bighorn has made a comeback, with conservationists working hard to reintroduce the species to areas from which it had been wiped out. Unfortunately, these efforts have hit a snag.

To thrive, the bighorn needs to migrate:

“They’ll climb for dozens of miles over mountainous terrain in the spring, ‘surfing’ the green waves of newly emerged plants. They learn the best routes from one another, over decades and generations. And for that reason, a bighorn sheep that’s released into unfamiliar terrain is an ecological noob. It’s not the same as an individual that lived in that place its whole life and was led through it by a knowledgeable mother.”

When herds are translocated (from a distant place of origin) they often fail to migrate across their new home range:

“…translocated sheep were often fitted with radio collars, allowing [researchers] to compare their movements to those of bighorns that lived in the same place for centuries. Within those longstanding herds, between 65 and 100 percent of the sheep migrated. But in the translocated herds, fewer than 9 percent migrated…”

Rather than being instinctive, bighorn migratory behaviour is learned – accumulated over time through prolonged experience of a habitat and passed down from generation to generation by example. So, yes, the remarkable truth is that sheep have ‘traditions’ through which knowledge of place is perpetuated over time.

Therefore, while an animal population can be restored through reintroduction (if the species survives elsewhere), the collective knowledge it accumulated is lost forever. For all the benefits of ‘rewilding’, the damage done by de-wilding is not easily reversed.

“…the lost animals aren’t just lost bodies. Their knowledge also died with them—and that is not easily replaced.”

Of course, if the development and continuity of shared knowledge is important to animals like the bighorn, it’s immensely more important to people. Human beings with their long childhoods, complex social structures and facility for language have an enormous capacity not just for learning but for passing on what we learn. And for most of the human story that has been through the mechanism of tradition.

Unlike the animals, however, we’ve also developed formal, theoretical systems of knowledge – that through writing and other media can be stored and communicated without the need for continuity of experience or practical example. There is immense power in that. Indeed, the modern world, with its universal reference points would be impossible without it.

These forms of knowledge are now so important, so ubiquitous, that we’ve forgotten that there are forms of knowledge that still require a living tradition to survive.

The Ise Jingu shrine in Japan is torn down every twenty years and rebuilt. This isn’t cultural vandalism, but the precise opposite. In the act of rebuilding, skills and memories are passed from the living to the living. The shrine is thus no more than one generation old, but also many centuries old – exactly as it was 1,300 years ago (and possibly even further back than that).

Not all traditions preserve culture with such fidelity. Most allow ways of life to take root and grow and adapt over time. They are conserved more than preserved, but nevertheless nourish individual experience with a sense of place and belonging.

Over-confident in our ability retain and extend knowledge by other means, modern societies have become astonishingly careless of, indeed hostile to, tradition. Statists and capitalists alike have demanded we uproot ourselves – relocating in the service of progress and efficiency.

We’ve gained from such flexibility, but not all of us to the same extent. The shared understandings lost through the death of tradition have left a bigger hole in some communities than others.

The political class, the corporate aristocracy, the academic elite: all those well-placed to flourish without tradition have abandoned those who aren’t.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe