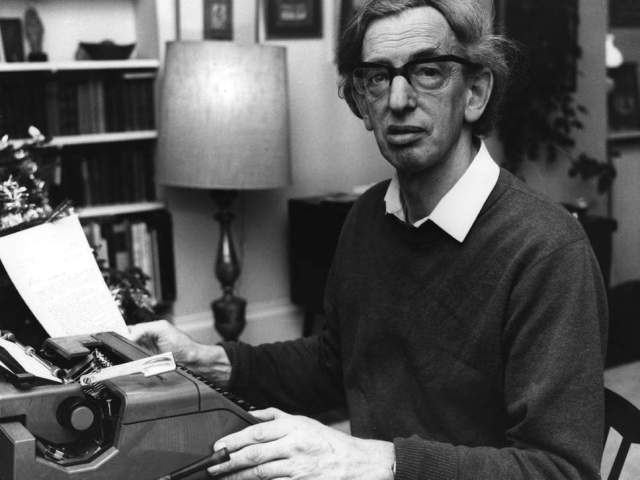

The early reviews of Richard J. Evans’ biography of the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012) fell into two distinct categories. From the one side came straightforward intimations of contempt, in which an “evil sod”, as one anonymous critic put it, was roundly excoriated for his want of patriotism, his sympathy for Stalin and his alleged treachery.

From the other came more measured accounts of his professional triumphs and the vagaries of his private life, punctuated by a steady drip of regret that he had never felt able to recant his support for the Soviet regimes of the 1930s. Even the Observer review by Neil Ascherson, a one-time pupil who spoke at his memorial service, admitted that his former tutor’s political statements up until 1956 – the year of the Hungarian uprising – “make unhappy reading”.

There is a quite a bit of unhappy reading in Eric Hobsbawm: A Life in History, which turns out to be overlong (650 pages of text plus another 100 or so of end-notes), over-admiring, over-defensive, and heroically over-absorbed in such weighty matters as the editorial finesse brought to bear on its subject’s autobiography, Interesting Times.

On the other hand, there are two areas in which Evans – Regius Professor of History emeritus at Cambridge and a world authority on the Third Reich – scores highly. The first is what might be called the question of Hobsbawm’s political upbringing in pre-Nazi Germany, from which his businessman father sprang him in 1933. The second takes in his conception of what the role of a Left-wing historian in a western parliamentary democracy ought to be.

To return to the intimations of contempt, there is no getting away from Hobsbawm’s inflexibility over Stalin, for it runs through his career like quartz through a rock. All very well for Evans to protest that the question put to him by Michael Ignatieff in a notorious TV interview (“What it comes down to is saying that had the radiant tomorrow actually been created, the loss of 15, 20 million people might have been justified?”) was “hypothetical”, but the fact remains that Ignatieff asked it and Hobsbawm by no means reluctantly answered “yes”. To Evans, the explanation lies in “tribal” loyalties: the reaction of a teenager who had seen Nazism at work, clung limpet-like to the only force he believed to be capable of opposing it, and could never quite bring himself to forswear the affiliations of his formative years.

Communism, to Hobsbawm, was never a ‘God that failed’, to borrow the title of that famous symposium from 1949 by a collective of ex-Communists headed by Arthur Koestler; it was simply a God who had made the fatal mistake of manifesting himself in the wrong place and at the wrong time: come the collapse of the Berlin Wall, he veered much closer to the traditional territory of the Labour pragmatist, for whom even an electoral pact with the LibDems was not too insensate a step if it meant the end of the hated Tories.

But as well as being a tribalist, Hobsbawm was also, as Evans shows in extravagant detail, a classic example of a type of apparatchik that Left-wing political parties of the 20th century, whether British or continental, have always hastened to attract: the intellectual guru.

In fact, Hobsbawm’s guru status, if such it was, looks to have arrived comparatively late on. He was already in his mid-sixties when he began to interview titans of the Labour movement for Marxism Today, and Evans offers amusing accounts of his sit-downs with such politicians as Tony Benn (whose diary suggests that he barely knew who his interlocutor was) and a waffling Neil Kinnock. As for his achievements in this line, Evans claims that Tony Blair “clearly felt he owed a debt to Eric for the part he had played in laying the intellectual foundations for New Labour”. And as for what this role might have amounted to, Evans is convinced that Hobsbawm helped bring about “the reorientation of the party towards an appeal to intellectuals in the broadest sense, to professionals and the urban middle classes as well as to its traditional base among the manual working class”.

If this makes the Sage of Nassington Road – no surprise to find that the Hobsbawms lived in Hampstead and gave glamorous parties there – sound like a reformed Bolshevik gaily welcoming the Mensheviks back on board, then it should immediately be said that the guru has a long and relatively distinguished history in 20th-century British political life. If, on the Left, the role was occupied at various times by such luminaries as Keynes, Harold Laski, G.D.H. Cole and Anthony Crosland (a bona-fide Labour intellectual whose The Future of Socialism (1956) was the first serious attempt to introduce his party to consumer materialism’s encroaching tide), then the Right, too, nearly always possessed a band of intellectual heavy infantry waiting for a chance to scuttle out into no-man’s land and lob a bomb into the nearest social democratic trench.

This was especially true of the Thatcherite revolution of the early Eighties. If Mrs Thatcher was, as Sir Alfred Sherman once put it, “a person of belief rather than ideas”, then her fascination with clever men and the intellectual ballast they could bring to the task of policy formulation was undimmed. Sir Keith Joseph; Sherman himself; the stalwarts of the Institute for Economic Affairs: all them played a part in Thatcherism’s unveiling 40 years ago and the different kinds of Conservatism let rip across the body politic in the decade that followed.

It would be overstating the case, here in 2019, to claim that the ‘party intellectual’ is more or less extinct, for there are still gurus busily at work on either side – Lord Willetts, say, for the Conservatives, or Paul Mason, the author of Postcapitalism, for Labour. But the Hobsbawm figure – the Hampstead intellectual with his Marxist quotation, falling over himself to remind you what Bevan said to Conference in 1953 – is as dead as the dodo.

Part of this, naturally, has to do with the widespread distrust of intellectualism that infects modern politics like a distemper, and set against which the Wilson cabinet, with its clutch of Oxford firsts, looks like a meeting of the British Academy. But another part has to do with the changing nature of political loyalties. Hobsbawm’s ‘tribe’ was the pre-war Communists, a political grouping whose ideology was founded on class and hostility to nationalism and in which women were barely allowed a ringside seat. In much the same way, most of the thinking of the current Corbyn Labour Party harks back to the kind of municipal-cum-Trade Union anti-European socialism in whose crucible its leaders were forged all of 40 years ago.

None of this, alas, cuts much ice with the 20- and 30-somethings who flocked to join the party after the 2015 election, for their tribal loyalties have moved on from social class to take in such items as identity, gender and eco-activism, while the communities that sustain them are more likely to be found in cyberspace than committee rooms in London N1.

The new Hobsbawm, if such a guru could now exist, would – you might hope – be a Crosland-style figure, capable of squaring the need for state intervention with the right to personal and economic freedom and reconnoitring the very considerable task of how to live decently in an increasingly pluralist age. The Hobsbawm of Richard J. Evans’ biography was, by the end of his long life, not so much an “evil sod” as an anachronism.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe