Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

On August 21, 2015, the conservative writer Ben Domenech wrote an analysis of the Republican presidential primary headlined: ‘Are Republicans for Freedom or White Identity Politics?’ Even at this early date, Domenech saw in the rise of Donald Trump the very real prospect that Trump could reduce the party to the “narrow interests of identity politics for white people.”

Three years later, and after Trump’s improbable victory in the presidential election, Domenech’s fear appears vindicated.

Most will remember the President’s reaction, back in August 2017, to a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville in which participants attacked counter-protestors and killed one. Rather than condemning the white nationalists he appeared to apportion blame equally: “hatred, bigotry and violence on many sides, on many sides”.

The President created more controversy later that year when he retweeted a British far-right group that was circulating misleading videos purporting to show Muslims engaging in acts of violence. And in August 2018, Trump endorsed a longstanding but false claim pushed by white supremacists that black South Africans were killing white South Africans and taking their farms.

Each of these episodes illustrates Trump’s apparent support for the racially inflected grievances that some whites express. And as our new book on the 2016 presidential election, Identity Crisis, demonstrates, it was this message that helped put Trump in the White House.

Academic research has shown that whites’ political opinions are frequently linked to their views of minorities. For example, whites’ opinions about a range of issues such as civil rights, crime, and social welfare programs are linked to how they view African Americans, and their opinions about anti-terrorism policies are linked to how they view Muslims.

But white group identity has typically been less prevalent and less potent when compared to minority group’s sense of identity with other minority group members. This is because group identity typically thrives under conditions of separation, marginalisation, and discrimination – conditions that are more commonly experienced by minorities. Thus, whites have not necessarily felt a strong connection to other whites or made political choices with their identity as whites at the forefront of their minds. By contrast, minority group members’ sense of connection to their own group routinely affects their political choices.

With Trump, that changed. American presidential campaigns have often trafficked in derogatory messages about minority groups – what’s been known as ‘playing the race card’ – but the 2016 campaign featured messages more closely connected to whites’ own sense of grievance.

In ‘activating’ white group consciousness, Trump made it a stronger predictor of how people voted. The salience of white identity was not evident in recent presidential elections precisely because it was linked to Trump himself. Just as Domenech feared, Trump made white identity politics a modern reality.

As a candidate, Donald Trump circulated memes from the white nationalist community and equivocated when asked to disavow support from the white supremacist David Duke, and he circulated false crime statistics that suggested most white murder victims are killed by African Americans.

More generally, his call to “make America great again” was routinely interpreted as a call to restore the privileges and status of whites. In one New York Times article, headlined ‘For Whites Sensing Decline, Donald Trump Unleashes Words of Resistance’, a Long Island housewife sums up the effect on some voters: “Everyone’s sticking together in their groups, so white people have to, too.”

While the combination of Trump’s message – and Clinton’s repudiation of it – did not increase white Americans’ own sense of grievance in the absolute sense, it did make whites’ existing group consciousness more strongly related to the decisions they made in the election.

This could be seen as early as the Republican primary. A January 2016 American National Election Study (ANES) survey showed a correlation between white group consciousness and people’s feelings about Donald Trump. For example, the more people believed that whites were discriminated against, the more they liked Trump. Notably, white group consciousness was not associated with people’s feelings about Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Bernie Sanders, or Carly Fiorina. Something was different about Trump.

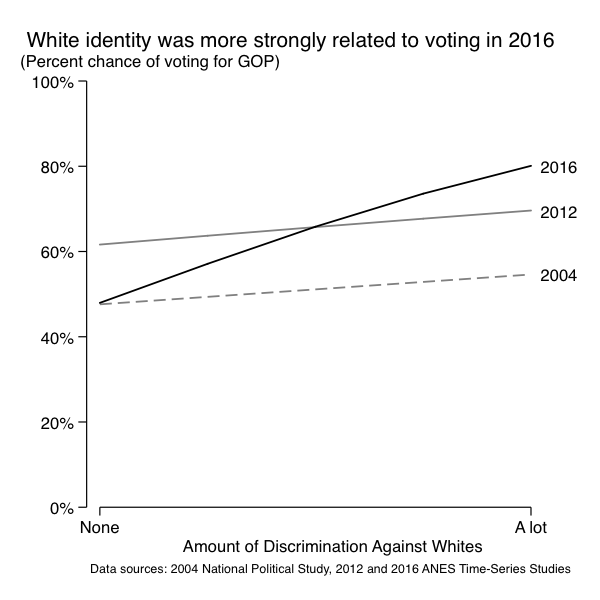

The same pattern emerged in the general election. The graph below shows the relationship between perceptions of discrimination against whites and how white Americans voted in three presidential elections where we have comparable data. Even after accounting for other factors, such as partisanship and feelings about African-Americans, perceptions of discrimination against whites were much more strongly associated with white voters’ decision to support Trump or Clinton, compared to their decision to support Obama or Romney in 2012, or George W. Bush or John Kerry in 2004.

One other finding also suggests that Trump himself was the key factor. In the spring of 2016, a separate ANES survey asked people how they would vote if the general election matched up Trump and Clinton, Cruz and Clinton, and Rubio and Clinton. The results are telling: perceptions of discrimination against whites were significantly associated with support for Trump over Clinton, but not with support for Rubio or Cruz over Clinton.

Since Trump’s election, there has been a substantial backlash against his presidency. It is visible in the many rallies of his opponents, in Democratic successes in the 2018 midterm elections, and especially in declining public support for Trump’s agenda – support for reducing immigration to the United States has declined, for example.

But these trends in public opinion are most prevalent among Democrats. The views of Republicans have changed much less, if at all. This is creating an even larger gap in how the two parties’ voters think about identity-related issues.

Which brings us back to Domenech’s question. Political science research has shown that presidents can influence their party’s image. Even though some Republicans have pushed back against Trump’s racially charged remarks, there appears at best a modest appetite to steer the party on a fundamentally different course. If that continues, then Trump’s presidency may increasingly tie the Republican Party to white identity.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe