They both exploded onto the intellectual scene from the frozen north, excoriating the laxity of the social assumptions of fashionable society and preaching a fierce message of moral seriousness that took the chattering classes by storm. Both insist upon a rule-based approach to ethics, and both are charismatic men who emphasise the importance of freedom and personal responsibility.

Both draw upon a version of Christianity as the moral sub structure of what is essentially a philosophy of self-help. And both have become such controversial figures that it is almost impossible to discuss their work without some people shouting.

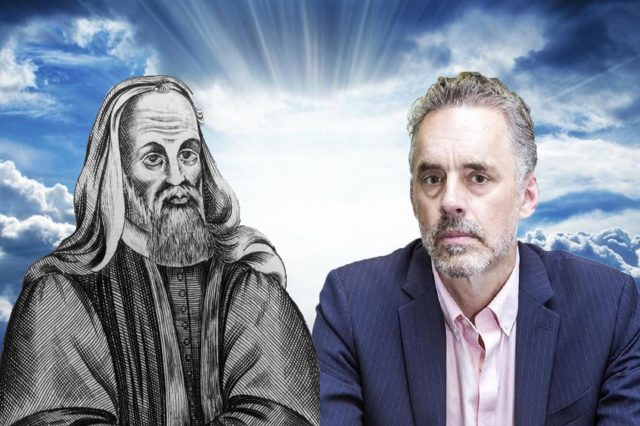

The Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson and the fourth-century Scottish theologian Pelagius have much in common.

My colleague, Peter Franklin, drew attention to this earlier in the week, when he wrote that “Christian critics of Peterson have accused him of ‘Pelagianism’ – the ancient heresy that sinners can save themselves by their own efforts.”

Pelagius has received a bad press throughout Christian history as the ultimate intellectual baddie, the arch heretic, the theological boogieman. But, to many people at least – even today – his teaching sounds exactly like what they imagine mainstream Christianity to be. God has given us the moral rules, says Pelagius, and the freedom to keep them. So keep the rules, and no excuses. And those that keep the rules will go to heaven and those that don’t will go to hell.

When Pelagius arrived in Rome preaching this uncompromising message of moral seriousness, he became an instant intellectual hit, his philosophy perfectly calibrated to appeal to those tired of Roman decadence and moral laxity. Rome was falling apart. Pelagius’s teaching could be easily described with the subtitle of Peterson’s bestselling 12 Rules for Life: an antidote to chaos.

Jordan Peterson, a psychologist and quasi-Christian theologian, draws upon the Bible to produce a set of moral rules designed to equip modern young men in particular to live better lives. Masculinity is in crisis, he explains. Just as the Christian God embodied the transcendent archetype of masculinity, so now that God is dead, masculinity knows not itself. So masculinity must rediscover its power – not the power of tyranny, but the power of competence. What use are the generations of man-babies we are producing, he asks? They need to grow up, become proper men: moral, strong and competent.

Many have attacked Peterson for his gender politics, though I am more sympathetic to him on this score than others on the Left. Indeed, I think there is a great deal to admire about Peterson’s work generally – his attack upon new atheism, and upon Sam Harris in particular, is spot on. When Christianity dies, argues Peterson, there is no reason to think that we will become better, more rational people, as Harris asserts. There is nothing irrational about every man for himself selfishness, nothing irrational about rejecting morality to get what you want.

Unlike Harris, Peterson takes Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky seriously: atheism may well not lead us into the sunny uplands of moral responsibility. Atheism could well be a moral catastrophe, destroying the communal basis for our moral codes at the very same time as (unconsciously) relying on them for some naive optimism about the moral future. Three cheers for Peterson on this score.

But, for me, where Peterson fails is precisely where Pelagius fails.

When Augustine came across Pelagius’s teaching he was both intrigued and appalled. The problem was twofold. First, Pelagius has a simplistic account of human nature and its relationship to morality. All this keeping the rules stuff is all very well, argues Augustine, but human beings are marked by weakness and failure. We are broken creatures, founded on, and shot through with, original sin.

Telling human beings to keep the moral rules and all will be well is a bit like telling an alcoholic to stop drinking and all will be well. That’s ok, as far as it goes. But such simple advice is never really going to work just like that because the alcoholic is broken and weak, and will in all likelihood fail again and again. Augustine saw Christianity as a moral philosophy for losers and failures.

See yourself as strong and competent, say Peterson and Pelagius. Know yourself as weak and deformed by original sin, says Augustine. Human beings are unable to fix themselves, says Augustine. That is why Christianity can never ever be reduced to a form of self-help. It is only God that can do the fixing, only God that can save us. It’s a message leant by Alcoholics Anonymous: admit your incapacity to help yourself and invoke a higher power.

This, then, is my difference with both Peterson and Pelagius. Both claim a Christian basis, but neither give God any work to do in their overall scheme of things. Both Peterson and Pelagius want human beings to be self-fixers. Augustine, on the other hand – and what became orthodox Christianity with the official denunciation of Pelagianism – believes that human beings cannot save themselves but can only be saved by God, and God alone.

Christianity is not about being strong and self-reliant. It is not about keeping all the rules. It is training in dependency. This needs emphasising. Augustinian Christianity is about learning to be dependent; Peterson and Pelagian Christianity is learning to be independent.

Pelagius attacked Augustine for providing human beings with too many excuses not to be perfect. His favorite line from the Bible was “Be ye perfect as your heavenly father is perfect”. It’s the theological equivalent of grow up and stand on your own two feet. And a great many of those who were influenced by Pelagius led extremely impressive lives. But ultimately, Augustine knows human beings far better than Pelagius. His philosophy of original sin is kinder and more forgiving, a teaching for those of us who are broken.

Likewise, Peterson wants man-babies to grow up and become strong, self-reliant men. In contrast, Augustine wants apparently strong, self-reliant men to recognise their fundamental dependency on that with is other. He wants self-reliant men to know themselves as babies. And in this regard, Augustine prefigures Freud by well over a thousand years.

Peterson tries to requisition Christianity in the creation of a moral philosophy of self-help. This pays Christianity the compliment of being taken seriously. And Peterson’s web lectures on the Bible are often brilliant, brimming with rich psychological insights. But for all his theological referencing, Peterson is wary and evasive when people ask him if he believes in God.

That’s why Peter Franklin is absolutely correct when he says that Peterson’s message, “though infused with Biblical references, is primarily psychological and ethical, not religious – specifically, it is not soteriological”.

And is also exactly the point where Christians must fundamentally depart from Peterson’s whole approach. And why his secular sermons won’t work in Christian terms. Because Christianity isn’t about morality, it’s about God and it’s about salvation. As Augustine taught: without God there is no salvation, and without salvation Christianity doesn’t add up to much.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe