Credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Today, we think of Silicon Valley as the cradle of technological innovation, but in the 1950s, people would have thought you were crazy if you set up a tech company in California. Most renowned technology companies had headquarters in Massachusetts along ‘Route 128’ near the research hubs of MIT and Harvard. Santa Clara County, on the other hand, was associated with nothing more advanced than apple trees until William Shockley came onto the scene.

Shockley was as close to a rock star as it got in the science world. Having won the Nobel Prize for co-inventing the transistor, many people thought he had gone mad when he moved to Palo Alto to found the Shockley Semi-Conductor Laboratory. But he had his reasons. He had grown up in the area, and he wanted to return home to help his ailing mother.

Shockley hired an all-star cast to join him – experts in physics, metallurgy and mathematics, they abandoned the East Coast to work on the commercialisation of the transistor. Robert Noyce, one of the hires, said getting the call from Shockley was like picking up the phone and talking to God.

Shortly after arriving, however, they discovered he was an erratic and difficult boss. He was a genius, but a jerk, and not just your ordinary, run-of-the-mill jerk. He was an epic egomaniac – and had tried to claim sole credit for the invention of the transistor. Later in life, he spent his time espousing a racist eugenics agenda, promoting a high-IQ sperm bank, and losing all contact with his children. He was, by most accounts, a horrible boss.

Within a year of joining Shockley, the new hires decided to leave and found a new company – Fairchild Semiconductor. Later dubbed the ‘Traitorous Eight’, they signed one-dollar bills in place of formal contracts – a symbol of nonconformity.

Many consider this act of employee treachery as the definitive moment of Silicon Valley’s creation. It set a precedent of ‘can-do’ entrepreneurialism and loyalty to lofty ideas, rather than individual firms and egos.

Noyce, only 29 at the time, was the ringleader and the group’s transistors expert. Eventually, Noyce and his colleague Gordon E. Moore outgrew Fairchild, and again poached employees to start Intel. In 1971, only three years after founding Intel, Noyce made history yet again with the invention of the Intel 4004, the world’s first microprocessor. He had invented the beating heart of the modern computer.

Silicon Valley owes its success to many things – access to capital, proximity to Stanford (one of the best universities in the world), and access to a vibrant Pacific hub in San Francisco. But what helped make it the innovation capital of the world is rarely discussed: California is one of the few states where non-compete clauses in work contracts are completely non-enforceable. In other words, employees have full rights to leave and work for a competitor.

In many other states, employees may be asked to sign a non-compete agreement as a condition of their employment. The terms vary considerably, but the basic idea is that if you are fired or quit your job, you cannot work for a competitor within the same industry for a certain period of time. These clauses make it difficult for workers to leave jobs and bargain for higher wages elsewhere.

Back in 1872, California made it illegal for employees to be bound to a specific employer. This state law is still in effect nearly 150 years later, and the lack of non-competes has proven a powerful factor in the Valley’s success. To this day, Boston lags Silicon Valley in the commercialisation of new technologies.

Imagine where the Valley would be today if Noyce had been prevented from defecting? What if Wozniak had never left Hewlett Packard to join Steve Jobs? Where we would be if Nikola Tesla were prevented from leaving Thomas Edison?

Silicon Valley’s history demonstrates that respect for worker talent was prized above strict company loyalty. This led to a malleable ecosystem, where good ideas spread quickly from company to company and innovators were free to choose their own fates. Professor AnnaLee Saxenian, author of many books on the tech industry, points out that, “In the early days engineers would say, ‘I work for Silicon Valley.’ And the idea was that they were advancing technology for a region, not any single company’s technology.”

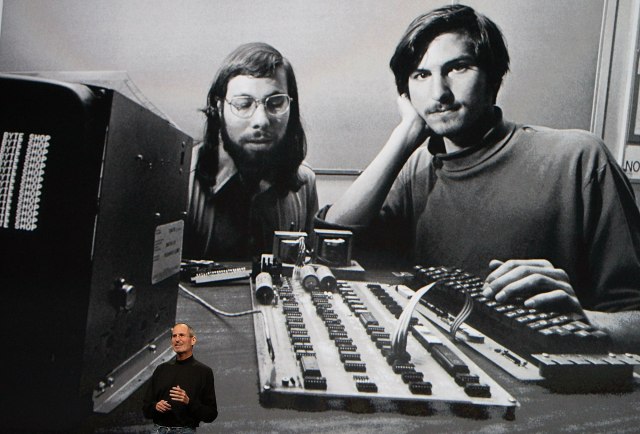

If Noyce thought Shockley was God in the early 1950s, Steve Jobs idolised Noyce in the 1970s. When Apple was starting, Noyce was already a legend with Intel. “Bob Noyce took me under his wing,” Jobs said. “He tried to give me the lay of the land, give me a perspective that I could only partially understand.” Jobs continued, “You can’t really understand what is going on now unless you understand what came before.”

Although Jobs worshipped Noyce, he failed to give his own Apple employees the same freedoms that allowed Noyce’s best innovations to flourish. In 2014, it came to light that Jobs had been preventing employees from moving to other companies. Silicon Valley was founded on freedom of mobility for workers, but the tech giants – Apple, Facebook, Google, Adobe and many others – were caught in “gentlemen’s agreements” to not poach each other’s employees. Staff brought the case forward claiming that these pacts made it difficult to market their skills and that they also suppressed their salaries.

As part of the lawsuit, emails came out in court between Steve Jobs and Eric Schmidt, the CEO of Google, “I am told that Google’s new cell phone software group is relentlessly recruiting in our iPod group. If this is indeed true, can you put a stop to it? Thanks, Steve.” In another email, Larry Page from Google sent a distressed message saying Steve Jobs had threatened war if a single one of his staff were hired.

In the end, the agreement not to poach went out across Silicon Valley. Google, Adobe and others developed Do Not Hire lists. This was clear collusion, and the tech firms were forced to pay a $324.5 million fine for their illegal non- compete pact.

The non-compete problem did not end there. These contractual arrangements are now spreading like an epidemic across the entire economy and hurting the poorest the most. Today non-competes cover almost 18% of the entire American workforce and nearly 40% have signed one in previous jobs. Only California and three other states (Montana, North Dakota and Oklahoma) ban non-compete agreements in the US.

Lawyers sometimes argue that these clauses help protect trade secrets, but is there any good reason to ask camp counselors, janitors, and personal care workers to sign them? There are already federal laws dedicated to protecting Intellectual Property and today even those who clearly do not possess trade secrets are made to sign them, including 15% of workers without a four-year college degree and 14% of people earning less than $40,000.

These employment clauses are found in a staggering percentage of America’s largest fast-food chains with minimum wage employees. Chains like Burger King, Carl’s Jr., Pizza Hut and, until recently pressured in 2017 to drop them – McDonald’s. These no-hire rules affect more than 70,000 restaurants – more than a quarter of the fast-food outlets in the US – according to Alan B. Krueger, who is an economist at Princeton University.

If you’re wondering what Pizza Hut has to lose if one of their store workers decides to work for another Pizza Hut across town, the answer is simple: the fewer options workers have, the less freedom they have to find a company that might pay a higher wage. The only function of these rules is to limit worker mobility and diminish their ability to bargain for wage increases. This is modern day feudalism, and workers have become vassals to corporate lords.

The truth is that non-competes only help firms that want tight control over employees. They do little for a given industry at large or for the economy. They harm workers and are disastrous for workers’ wages.

Often employees do not realise they are signing away their right to work somewhere else, as firms are not legally obligated to disclose non-compete clauses in almost all states. According to a study by economists Matt Marx at MIT and Lee Fleming at Harvard University, barely 3 in 10 workers were told about them in their job offer, and in 70% of cases, they were asked to sign them after they had already accepted the offer and turned down any alternatives. Half of the time, non-compete agreements were presented to employees on or after their first day of work.

Barring workers from moving in search of better opportunities only works in an environment where firms have all the power. Because of industrial concentration, a number of firms now have monopsony power – that is, they are the only buyers of labour. A monopoly means there is one seller, and a monopsony means there is only one buyer.

In a monopsony, workers have little choice in where they work and have little negotiating power for wages with employers. In a healthy economy, many firms would be competing equally for workers and would be incentivized to entice new hires with higher wages, better benefit packages, and few restrictions on their next career moves. But monopsonies make it easier for firms to depress worker wages. The classic example of this is a coal-mining town, where the coal plant is the only employer and only purchaser of labour. Today, in many smaller towns, Walmart is the new coal plant – and is the only retail company hiring.

With burdensome occupational licensing, forced arbitration, and increased industrial concentration thrown into the mix, American workers are now faced with pressure on all sides. Without a strong union movement to provide a countervailing power, American workers are left to fight alone.

This is a toxic cocktail. The hangover from increased corporate power is real, with many struggling to meet basic needs. This is not the free capitalism we need or the hope that drove the ‘traitorous eight’ in Silicon Valley decades ago. Workers deserve better.

This is the second of three extracts from “The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition” a new book co-authored by Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe