Some battles, sadly, have to be fought over and over again. Even the most shocking practices, such as female genital mutilation, have their defenders, ready to revive bad and discredited arguments whenever the opportunity arises. The UN has campaigned against FGM for years, using high-profile figures like Angelina Jolie to make the case against cutting girls’ bodies for the sake of nonsensical ideas about desire and sexual hygiene. Yet a federal judge has thrown out the very first prosecution of doctors and parents ever to take place in the US, potentially setting back the campaign to protect women and girls by decades.

It has to be said at once that the case was lost on a technicality. The judge ruled that outlawing FGM is a matter for individual states, arguing that Congress did not have the authority to pass a 1996 law that prohibited it across the board. The judgment is likely to be appealed but one of its disastrous effects is to make further prosecutions of FGM practitioners extremely difficult at a time when it’s believed that the practice is becoming more widespread. Immigration from countries where FGM is common means that more than half a million women and girls in the US are believed to be at risk, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Ominously, the failed prosecution has energised defenders of FGM, who claimed in court and TV interviews that all that was done to nine child victims was “female circumcision” or a “ritual nick”. The medic who carried out the procedure, Dr Jumana Nagarwala, belongs to a small Shia Muslim sect, the Dawoodi Bohra, some of whose members have their daughters cut in defiance of the longstanding (and previously unchallenged) federal ban in the US. Her lawyer claimed that she had merely carried out a protected religious procedure that didn’t involve removing the clitoris or labia, unlike the most extreme form of FGM.

In reality, FGM is much more a cultural than a religious practice, originating in Africa where it is still carried out in many countries. And while it is bad enough to hear people defending any species of unnecessary surgical procedure on girls’ bodies, doctors who examined the child victims found plenty of evidence of harm; they discovered scar tissue and lacerations to the girls’ genitalia, while one victim said she was in so much pain she could hardly walk.

Some of the girls cried and screamed during the procedure and one was given Valium ground into liquid Tylenol to keep her calm, according to court records. Two of the victims were just seven years old when Dr Nagarwala performed these procedures on them, using a private clinic in Detroit owned by another doctor who also faced charges.

FGM is controversial even among members of this sect, which originated in western India, and some actively oppose it. They are worried by the outcome of the Detroit trial, believing that it sends a dangerous message to countries where huge numbers of girls are still being mutilated. “Unfortunately this is going to embolden those who believe that this must be continued… they’ll feel that this is permission, that it’s OK to do this,” said Mariya Taher, who was herself a child victim of the same type of FGM.

In western and developing countries alike, some of the most effective campaigners against FGM come from communities where it is still practised, often women who were forced to undergo the procedure themselves when they were children. Many of them are justifiably angry about something that was done to them without their consent, with potentially catastrophic consequences for their sex lives and ability to give birth safely. In some good news, the British government has committed to spend £50 million on grassroots programmes to stop FGM across Africa by 2030.

Yet if the failed prosecution has achieved nothing else, it has at least focused public attention on a practice that happens in conditions of great secrecy in western countries and is notoriously difficult to prosecute. In the UK, where an estimated 137,000 women and girls have been subjected to FGM, there has not yet been a single successful prosecution.

The police say it is carried out behind closed doors, with parents and practitioners taking care to leave no evidential trail, and children are often too frightened to testify at trials that might send their mother or father to prison for up to seven years. But mandatory reporting by health professionals is gradually uncovering the extent of the practice in the UK, with more than 6,000 cases being recorded by midwives and obstetricians between April 2017 and March 2018. These are adult women who may have been cut abroad, when they were children, although it may be an indicator that their own female children are at risk of FGM in this country.

More than 200 million girls and women have been cut in 30 countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, according to the World Health Organisation. In countries such as Sierra Leone, where FGM is still legal, almost 90% of the female population aged between 15 and 49 has been cut, causing a huge range of health problems and high rates of maternal mortality.

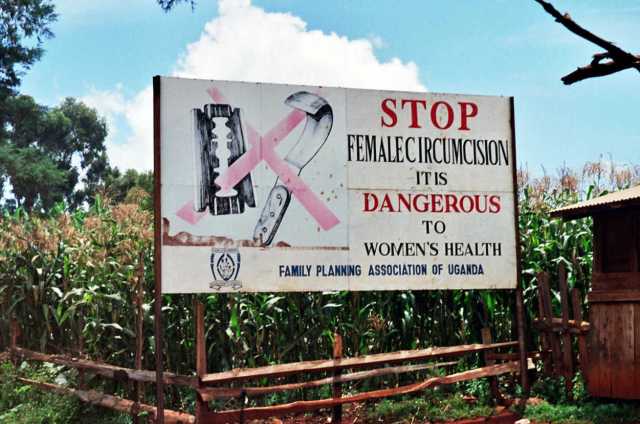

Cultural pressure is relentless and hard to resist, according to a recent report by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, which noted that girls in Sierra Leone who try to avoid FGM are accused of being unclean, promiscuous or carrying disease. Even in countries such as Egypt, where FGM was outlawed in 2008, the practice continues and is often carried out in insanitary conditions by older women with no medical knowledge. There have been horrific cases of girls and even babies bleeding to death after being cut with knives or razor blades.

Changing the law is an essential step in protecting women and girls but changing ideas is just as important. It is a shocking fact that some western liberals used to defend FGM as ‘part of their culture’ without looking too closely at who ‘they’ were – namely the cutters who made money from it, and the men who wanted ‘pure’ wives who found sex too painful to have extra-marital relationships.

It is only two decades since the feminist writer Germaine Greer argued in one of her books, the whole woman, that banning FGM was “an attack on cultural identity”, rightly drawing a rebuke from MPs on the international development select committee. In an unintentional illustration of how important language is in these matters, Greer also made the wildly insensitive observation that “one man’s beautification is another man’s mutilation”. She has long been regarded as a maverick but it is worth remembering that cultural relativism, while widely and rightly discredited, has never completely gone away.

That is why the outcome of the American court case has the potential to be so damaging. The judge was clear that his decision didn’t amount to an endorsement of FGM but that won’t be the headline in parts of Africa and Asia where generations of cutters are determined to keep the practice going. Hearing it sanitised as just a ‘nick’ in an American courtroom is deeply alarming, and needs to be challenged in every available forum.

FGM is misogyny in its bleakest form, denying girls control of their own bodies and threatening their lives in the most extreme cases. It is a gross abuse of human rights, wherever it happens, and western countries have a duty to make sure that both their laws and language lead by example.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe