Credit: Carsten Koall/Getty Images

This week, before blowing hot and cold over Putin, Donald Trump was attacking Germany for becoming “a captive to Russia” as it supported a gas deal with Moscow, rather than paying its fair share of the Nato budget.

“We’re protecting Germany, we’re protecting France, we’re protecting all of these countries,” said the President. “And then numerous of the countries go out and make a pipeline deal with Russia where they’re paying billions of dollars into the coffers of Russia.”

He’s wrong. While it’s true that Berlin has given its support to the building of NordStream II, a pipeline that will bring Russian gas directly to Europe via the Baltic Sea, Merkel insists the project is a private venture and is not funded by her taxpayers. Gazprom is the sole shareholder in NordStream II AG, and the Russian energy concern is paying half the cost of the pipeline. The remaining half is being covered by five western energy firms: ENGIE, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Wintershall and Uniper.

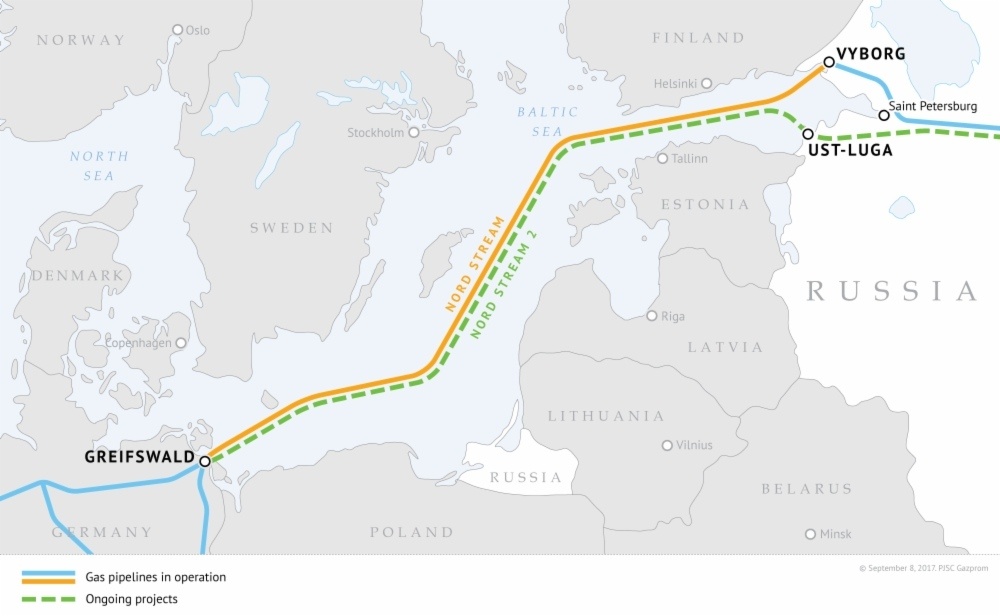

Nonetheless, the 1,200 kilometre, $11 billion billion pipeline that will connect Ust-Luga near St Petersburg with Lubmin near Greifswald in Germany is creating bad blood between Germany and various other European countries.

Shadowing NordStream I, which came on stream in 2011, NordStream II would effectively double the amount of gas Germany takes from Russia (currently about 40% of total German consumption). About a third of this would be re-exported across northern Europe. Since there is a parallel SouthStream project from southern Russia to Turkey, which would interconnect with the gas hub at Baumgarten in Austria, the total amount of gas transiting Ukraine would fall from 90 billion cubic meters to between 10-15 bcm.

Unlike Poland, Ukraine and various other nations, Merkel is happy that construction is underway, insisting it is an economic proposal, not a political one – one that will bring cheaper energy to Germany. Finland and Sweden have also approved the project – albeit with some concerns voiced by Sweden’s intelligence service about the proximity of the Kallhamn harbour Gazprom wishes to use for pipelaying vessels to a major naval base at Karlskrona.

But Denmark is holding out, since the work might damage valuable fauna within Denmark’s exclusive maritime zone. This is not insurmountable, since the main pipe-laying contractor Allseas says the route can be changed, at roughly 5% additional cost.

Geopolitically, though, the new pipeline is highly contentious and it also infringes the EU Third Energy package, which does not allow a monopoly supplier to also own the pipelines and gas distribution networks.

Most obviously, NordStream II cuts out existing gas transit nations such as Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine, which earn roughly €1 billion a year in transit fees for Kiev alone. The Baltic States don’t like it either as gas could be used as a geopolitical tool, as was the case with Ukraine in 2006 and between 2008-09 when the Russians cut off the supply over unpaid bills.

Chancellor Merkel has reassured President Poroshenko of Ukraine that Russia will not suddenly shut down the gas passing through Ukraine, and Putin has also declared that is not his intention. But who would trust him?

The US, meanwhile, opposes the pipeline because it wants Europe to wean itself off its dependence on Russian gas. Though since it is also doing its best to inhibit development of Iranian gas fields, the opposition may be connected with a desire to sell Europe a lot of US shale-derived LNG – which would also correct what the Trump administration sees as an EU-US trade imbalance. At present, most of this US gas goes to Asia where prices are higher, but who can tell what may happen in future.

Naturally, the Trump administration denies that its objections to NordStream are venal, pointing out the Obama administration’s similar reservations. Besides, there is a global LNG market so Europe, whose LNG terminals are only working at 25% capacity, could just as easily take LNG from Algeria, Australia or Qatar – as one can see at Milford Haven – in the event that the much cheaper piped-gas supply from Russia was interrupted.

Germany continues to robustly defend the pipeline, saying that it will reduce its own dependence on coal (Merkel is also committed to eliminating nuclear). It also claims it would be a more reliable reverse flow re-supplier for Eastern European countries worried about Russian energy blackmail, and that it would be no bad thing for the Ukrainian economy to wean itself off passive dependence on gas transit fees.

There are also hard, unignorable, facts about future European gas supplies. The Dutch fields around Groningen are producing less and less (12 billion cubic meters by 2022) and by 2030 will be exhausted. Last year, the Netherlands became a gas importer for the first time in its history. Norway is not an endless resource either.

Berlin refuses to make the connection between a gas deal and wider western security of the kind that informed Trump’s crude attacks at the pre-summit breakfast. Germans believe that engaging with Russia is better than constantly provoking it – a view supported by vast swathes of German big business. It is worth pointing out here, though, that former German chancellor Gerhard Schroeder[1. ‘Schroederisation’ is now a verb to describe the corruption of one country’s former leaders by those of another. Like Blair he is also a ‘clacquer‘ for autocrats. He was in the front row at Putin’s recent inauguration, several rows ahead of fellow Putin enthusiast, the bloated Hollywood tough guy Steven Seagal. Many Germans find his cosy relationship with Putin quite nauseating.] (also chairman of Rosneft) is head of the NordStream II shareholders committee. He is as tainted in Germany as his friend Tony Blair is in Britain by his over-eager involvement in big money making.

As for Putin, sketching his pipelines like advancing tank columns, he has found another area which he can use exacerbate divisions within the West, between Germany and its eastern neighbours, and between Berlin and the Trump administration.

There is a further consequence. This week a high-level EU delegation, led by Jean Claude Juncker and Donald Tusk, is in Beijing to explore European level-playing-field access to the Chinese economy. While there are significant disagreements, both sides intend to protect and reform the WTO in order to preserve a globalised world trading order that has been good for both sides. Both implicitly view this as a riposte to the Trump administration’s imposition of escalatory tariffs.

They are also likely to reaffirm their commitment to an Iranian nuclear deal that the US is bent on subverting. The latest sign of this has been US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s refusal to issue waivers to European companies which work in or with Iran, such as the car maker Peugeot and oil giant Total.

Little shards of ice are forming in European hearts as they contemplate six more years of the Trump administration. Now that Trump has publicly ranked them as ‘foes’ equivalent to Beijing and Moscow, they will be looking for strategic alternatives.

While a few may turn towards Putin and his visions of a vast Eurasian bloc (this seems to appeal to Hungary’s leader Viktor Orban), many more will be looking much further East towards China.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe