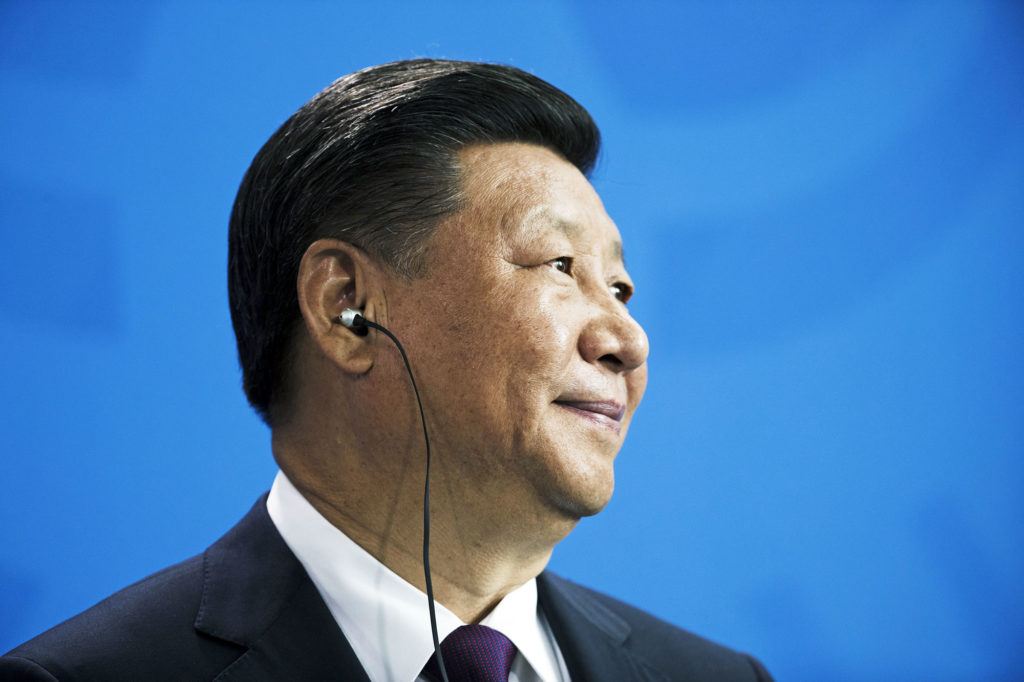

Gregor Fischer/DPA/PA Images

Western democracies seem trapped in the instantaneous, in which the 24/7 media conspire with every low-grade politician to obfuscate the serious with the trivial, while their systems slide into dysfunctionality.

By contrast, China is ruled by well-educated technocrats who have spent half their lives being stress-tested in a series of major appointments, whether in coastal or interior regions, or ones with ethno-religious tensions. The medium provinces are as populous as Spain. It is striking that the last British CGS, Lord Richards, regards President Xi as the last serious world statesman standing.[1. The nature of careers in the CCP can be understood from Kerry Brown, The New Emperors (London 2014) and Richard McGregor, The Party. The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers (London 2012)]

Xi’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) strategy is the main element in his American-style ‘China Dream’. It spans Central Asia, the greater Middle East, and Europe, as well as many of China’s regional neighbours.

So far $1 trillion is being pumped into colossal infrastructure projects, on land and at sea, involving 65 countries. Some of OBOR is already a reality, for since September 2015, freight trains have been arriving in Duisburg and Hamburg from Zhenzou in China. The Hinkley Point Chinese-French nuclear plant is officially billed as an OBOR project, implying that the British may participate in what is a global showcase for Chinese technology.

By contrast, nothing much has come of an OBOR Economic Corridor linking Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar, and at the $600 million dry port of Khorgos, there is much bustle on the Chinese side, but little happening on the Kazakh one. Some elements of OBOR in central and southern Europe look like common or garden direct foreign investment, for example the Czech Republic’s Slavia Prague championship winners and some local media are now owned by the Chinese.[2. Tom Hancock ‘China encircles the world with One Belt, One Road strategy’ Financial Times 4 May 2017 for the ‘dry port’ of Khorgos]

OBOR is both an exercise in rebranding of earlier schemes, a showcase for Chinese ‘can do’ and a political system that makes long-termism possible, but it is also a domestic economic strategy with geopolitical effects.

An advert for authoritarianism?

Both Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao sought to develop the relatively backward Chinese West by increasing its connectivity to China’s ports. Xi’s version adds overland elements, with various corridors linked into the main belt linking China to Europe via Central Asia. OBOR reflects China’s disappointment on the returns on its US dollar assets, as well as an opportunity to consolidate and reform chronically ailing State Owned Enterprises, while appointing Communist party secretaries as company chairmen.[3. Hongying Wang ‘A Deeper Look at China’s “Going Out” Policy’ Center for International Governance and Innovation 8 March 2016 and Greg Levesque ‘China’s Evolving Economic Statecraft’ The Diplomat 12 April 2017 for SOE CEOs and the CCP]

OBOR is also a massive exercise in soft power projection, at a time when every caustic Tweet by Donald Trump undermines that of the US by casually alienating allies from Australia via Germany to Mexico.

OBOR implicitly makes the claim that only China’s authoritarian-capitalist model can devise and realize long-term strategic projects, which are billed as a ‘win-win’ for every participant. Much the same logic underpinned China’s remarkable growth from Deng Xiaoping onwards, for there was no public opinion, rule of law, or independent institutions to oppose transformative initiatives. For example, no ‘defence lobby’ stood in the way of Deng’s diversion of manpower (1.5 million troops to be precise) and resources from the PLA to new factories in an era when China opted to fight two brief minor wars with India (1965) and Vietnam (1979).[4. Ezra F. Vogel, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (Cambridge, Mass 2011) pp. 540-551]

Mixed delivery

China’s government would claim that only their system is prepared to countenance failure as well as success. That is just as well since OBOR has involved investing money from Chinese banks in some very unstable places.

Already, the brief history of OBOR is littered with examples of things that did not work out so well. There are faulty power plant in Botswana and a loss-making railway in Laos. Kenyans paid $5.6 million per km of railway track, or three times the international rate. Projects often suffer from cost overruns, poor management, and fail to deliver the local benefits as advertised.[5. Spencer Sheehan ‘The Problem Financial Times With China’s One Belt, One Road Strategy’ The Diplomat 24 May 2017]

There is also the issue of ‘investors’ becoming ‘infestors’ as a xenophobic Ugandan politician put it. In various countries, the Chinese habit of dumping their expat workforce has stimulated local resentments, from the poultry market in Lusaka to taxi drivers in Daresalam. In Casablanca, of all places, Chinese merchants easily out haggle the Derb Omar souk’s finest, for with its proximity to Europe, Morocco is another major object of Chinese activity. This brings us to the geopolitical ramifications of OBOR.[6. Arthur Waldron (ed) China in Africa (Washington DC 2009) pp. 146ff and ‘Overseas and under siege’ The Economist 11 August 2009 for anti-Chinese riots in Algeria]

Chinese foreign policy is based on a business is business model, save for recognition of core Chinese interests such as the South China Seas (where the Czechs and Hungarians are already on side) or Taiwan, where a lot of investment has changed minds on recognition in Central America and the Caribbean. In other words, much of China’s foreign policy is about China itself, generously construed, just as 80 per cent of the focus of even its external intelligence agency is on China’s own population.

Future dangers

But for how long can China’s desire to ‘go out’ into the world be compatible with an agnostic stance to geopolitical problems even if Bejing practices a hear no evil, see no evil line on human rights?

The growing Chinese diaspora beached by OBOR is one concern, for should anyone mess around with the 1 million expats in Africa, Chinese ‘netizens’ will soon be posting their leaders calcium tablets to grow a backbone. That is one justification for a blue water navy, for the ad hoc arrangements in evacuating 30,000 workers from Libya in 2011 after the British and French plunged it into chaos may not suffice.

Many OBOR projects are in countries with major security problems. China is investing $55 billion in Pakistan, with the port of Gwadar linking China to the Middle East. It is also building 21 coal fired power stations, as well as roads and railways, and leasing vast tracts of agricultural land for experiments with irrigation and new seeds. Some Pakistanis fear the reappearance of an East India Company with a Han face.

Since much of this work will be in places where contractors can be kidnapped or killed by religious terrorists, China has deployed its Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, originally consisting of Korean War veterans but then used to operate enterprises in Xinxiang, while insisting that Islamabad deploy 12,000 troops to protect Chinese workers. Increased arms sales to Pakistan, for example ships to protect Gwadar, are worrying India.[7. Henny Sender and Kiran Stacey ‘China takes ‘project of the century’ to Pakistan Financial Times 17 May 2017]

Strategic concerns about OBOR are also abroad in the Middle East. For sure, OBOR will benefit several Gulf countries (especially Oman and Qatar) and China has been assiduous in maintaining neutrality in the sectarian clash between Iran and Saudi Arabia, where Chinese banks are crucial for raising money for Mohammad bin Salman’s grandiose Vision 2030. But there is no disguising the fact that for geographical reasons Iran is at the heart of OBOR, while China has lined up with Tehran too in supporting President Assad in Syria. At some point, a more powerful China may be sucked into these various miasmas, even though many Chinese foreign policy experts warn that the US would love to see China expending its blood and treasure in these pointless places. So yes, OBOR is an advert for things China can do very well because of its decennial strategic perspective, but with each new mile of road and rail, the geopolitical complexities for China grow in scale.[8. Giorgio Cafiero and Daniel Wagner ‘What the Gulf States Think of ‘One Belt, One Road’ The Diplomat 24 May 2017]

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe