Credit: Erich Schlegel / Getty

By all rights, Donald Trump should have his power clipped after this autumn’s midterms. Fully 53% of Americans disapprove of his performance so far, and his Republican Party trails the Democrats by over 8% in the polls.

Nonetheless, the Republicans are expected to retain control of the Senate, perhaps even gaining some seats; analysts also reckon the party is in with a fighting chance of hanging on to a slim majority in the House.

How is this possible? In most countries with only two major parties, an eight-point lead would guarantee a strong Democratic majority whether a country used a proportional representation system or an American-style first-past-the-post(FPTP) approach. In both Jamaica’s 2011 elections and the Bahamian 2012 elections, for example, victorious margins of nearly 7% gave the winning parties huge supermajorities of legislative seats.

But America’s unique electoral laws and political geography currently mitigate against the Democrats. The party’s strength is not evenly spread throughout the country. Instead, it is highly concentrated in urban areas, especially in those dominated by ethnic majorities. Democrats will win these seats with extreme margins of up to 90% more than their Republican challengers, but those surplus votes are useless, since they only count within the seats where they are cast.

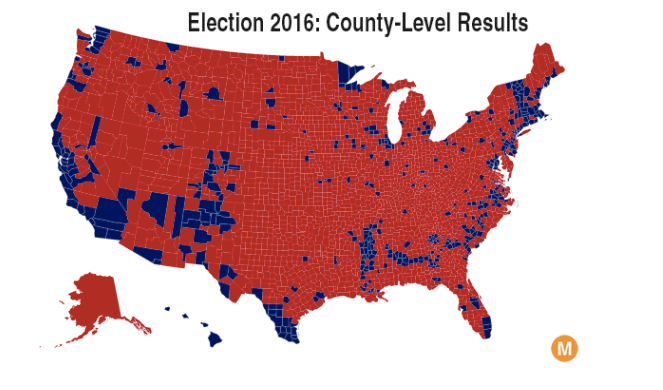

Republican strength, however, is more evenly spread throughout the country, allowing them to win more seats with fewer votes. We know all this from the 2016 election results. The Demographic disadvantage is easily seen on a map of the election returns.

Source: Metrocosm

Note how little of the country Clinton won (the blue areas). While it’s true that the blue areas are much more densely populated, the truth is that she won three million votes more than Trump by running up her margins in areas where the Democrats already did well. Trump exploited that geographic shortcoming to win the Electoral College despite his massive vote deficit.

That much is now well-known. But what is less familiar is that this advantage extends down to the Congressional district level. Trump won 230 of America’s 435 House seats despite losing the popular vote by over 2%. He won the median House seat, that 218thseat which confers a majority, by 3.4%. The battle for the House, then, is being fought on very Republican turf.

This built-in advantage is compounded by America’s politically-driven method of drawing legislative district lines. District lines in most states are drawn by the state legislature, not a non-partisan body, after each decennial census. The party in control normally draws lines for its own political advantage, a process known in America as “gerrymandering“. While both parties have done this for decades, Republicans controlled many state legislatures after the 2010 elections and hence were in a strong position to draw favorable lines after that year’s census. The resulting skewed maps easily add a net 10-15 seats to the national Republican House total.

Political analysts have concluded that Democrats will need to win the national popular vote for the House by about 7% to gain a bare majority of the seats. If the polls are correct, then they are on track to retake House control, but only by the very narrowest of margins. But a slight improvement in Republican fortunes could allow them to retain the House even as they heavily lose the popular vote.

The outlook for Democrats in the Senate is even worse. Senators are elected from a whole state to a six-year term of office and the elections are staggered so that only one-third of the Senate is voted on in each biennial vote. Of the 35 seats up for election this year, Democrats hold 26. The chances of them winning more – which they would need to do to take control – are slight.

Trump carried 10 of the states where Democratic incumbents are trying to hold on to seats; he won five of those by between 18 and 41 points. Republicans hold only one seat in this election that Hillary Clinton carried, and only one other seat that Trump carried with less than a majority of the vote. To take control, Democrats would have to keep their 26 seats and take those two Republican ones. This is deemed to be extremely unlikely, especially since polls show that people who voted for Trump in 2016 remain very likely to vote Republican in the fall.[1. The system may seem undemocratic, but it isn’t unusual. There are many countries with systems that give a majority of seats to parties that win a minority of the vote. The party with more votes in Australia, for example, has received fewer seats five times since the Second World War. The same has happened twice in Norway and once (1951) in the United Kingdom. The margins in those elections, however, never exceeded 3%.]

The Democrats are well aware they need to broaden their appeal. As a result, many candidates running in Republican-leaning seats are saying that, should they win, they will not vote for the current House Democratic leader, Nancy Pelosi, who has been deemed ‘too left-wing’ by her opponents; by distancing themselves from her, they hope to win back some of those Democrats who voted for Trump.

Democratic Senate candidates running in the very Republican states are also trying to set themselves apart from the often-virulent anti-Trump tenor of the Democratic base. They know they will need Trump voters to win, and those voters won’t back someone who is dead set against the President they support. It remains to be seen, however, whether such tactics will pay off.

As things stand, the Democrats are still the favourites to retake the House, but the fall-out, should they win the popular vote and have nothing to show for it, could be intense. It’s one thing to lose an election: it’s quite another to feel robbed. Observers who think American political combat is intense, shrill, and dangerously divisive might remember this current atmosphere as being quaintly civil if Democrats again represent a majority denied.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe