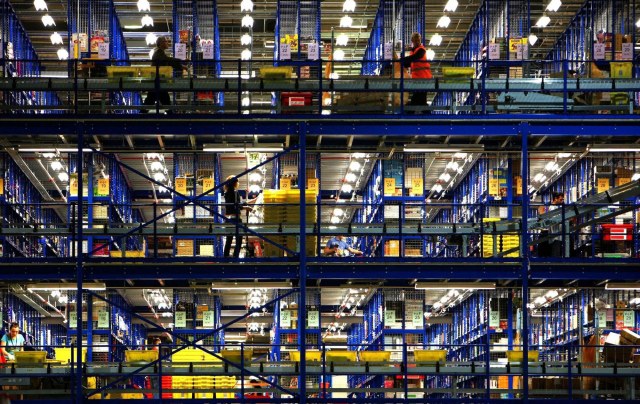

Amazon workers near Milton Keynes. The company is known for close monitoring of its workforce. Credit: Chris Radburn/PA Images

“In the past the man has been first; in the future the system must be first.”

~ Frederick W. Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management

While most grand political narratives had lost their appeal by the close of the 20th century, utopian thinking as applied to the workplace made it into the 21st century unbowed. In 2001, a book written in 1911, The Principles of Scientific Management, was voted the most influential management book of the 20th century by the Fellows of the Academies of Management[1. https://www.bus.lsu.edu/bedeian/articles/MostInfluentialBooks-OD2001.pdf]; its effects can still be seen in workplaces today.

In the book, Frederick Winslow Taylor, a mechanical engineer from Philadelphia, argues for the perfectibility of human labour through the application of pure reason to the shop floor. “Scientific management”, the meticulous measurement and recording of workers’ movements to maximise productivity, aims to turn human labour into the equivalent of machine labour.

The purpose of Taylor’s initial experiments was to eliminate “unnecessary motions” during the handling of pig iron, but he insisted that his theories could be applied to all classes of work. “Every single act of every workman can be reduced to a science,” he wrote. His workers were closely observed, photographed and timed. Those who failed to meet the exacting standards of scientific management theory were sacked.

Importantly – inevitably, perhaps – the worker under experimentation was not deemed to be quite human and the book is littered with references to a working class that is “too stupid” and “too mentally sluggish” to understand the theories. In fact, he seemed to view early 20th-century American society in the same way Thomas Hardy viewed late Victorian England, as a division (in Hardy’s words) of the “mentally unquickened, mechanical, soulless; and the living, throbbing, suffering, vital, in other words into souls and machines, ether and clay”.

It’s an attitude that gives his approach more than a flavour of managerial Leninism: an intellectual vanguard directs the masses who are “incapable of understanding this science”; there is a difficult transitional period in which “both sides will rebel” against the new system; and finally, a new era will bear witness to a “complete change in the mental attitude of all the men in the shop toward their employers”. Conflict is resolved and the interests of employer and employee converge.

“In the end, the people… will force the new order of things upon both employer and employee,” writes Taylor with a zeal to rival any Bolshevik[2. There is a neat irony here in that Rakhmetov, the central character in Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s 1863 novel What Is to Be Done?, is an archetypal Taylorian character. He divides his work day up into units of a quarter-hour for every task while forsaking all recreation. Lenin liked the book – and the asceticism of its main character – so much that he purloined the title for one of his own revolutionary tracts.].

Parallels with communism are also apparent in his admonitions to his disciples not to abandon the one true path. The implementation of scientific management without its accompanying “spirit” will lead inexorably to “failure and disaster”, Taylor warns, pre-empting by several decades Leon Trotsky’s warnings about a revolution betrayed.

And Taylorism lives on under the aegis of capitalist progress. At the extreme end of things, we have the Chinese state’s development of a technology that monitors workers’ brainwaves in order to boost production[3. https://uk.businessinsider.com/china-emotional-surveillance-technology-2018-4] (no doubt justified with an occasional reference to Lenin). Closer to home, Amazon has patented wristband technology that would allow it to monitor where its workers are placing their hands while they are picking and packing orders[4. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jan/31/amazon-warehouse-wristband-tracking].

This is very similar to a process developed during early experiments conducted by a Taylor Society member, Frank Gilbreth, whereby a “Bricklaying System” was devised that prescribed the ideal number of movements to lay each brick – it was brought down from 18 to five. Even the number of times a bricklayer was permitted to tap each brick as it was placed on its bed of mortar was tightly monitored by Gilbreth.

Amazon’s pickers and packers are already made to carry around a handheld tracking device which times their actions and monitors their productivity. Yet, as I discovered while researching my book, the labour policies deployed by the world’s largest multinational show little interest in the welfare of those at the bottom of the pile. Which does appear to concern Taylor, for all his intellectual condescension.

His book ends with a rallying cry on behalf of the consumer, whose rights are “greater than those of either employer or employee”. That’s because Taylor believes it is the consumer who will bring the appropriate pressure to bear on firms which reject his doctrines. The people “will demand the largest efficiency from both employers and employees. It will no longer tolerate the type of employer who has his eye on dividends alone, who refuses to do his full share of work and who merely cracks his whip over the heads of his workmen and attempts to drive them into harder work for low pay.”

While this populist message might seem to contradict some of the preceding material, a moralising tone can be detected in the book. For all his contempt of the “stupidity” of the working masses, it appears to bother Taylor that more unscrupulous overseers may yet use his doctrines to do ill by their employees.

Yet Taylor’s faith in the ethical conscience of the consumer to step in and prevent exploitation was perhaps misplaced. For as far as Amazon are concerned – the nearest we have to a contemporary Taylorist behemoth – it is precisely public indifference that has allowed Jeff Bezos to slough off the doctrine’s paternalist component. But, then, writing more than 100 years ago, Frederick Taylor can be forgiven for not reckoning with the dissociative power of online shopping.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe