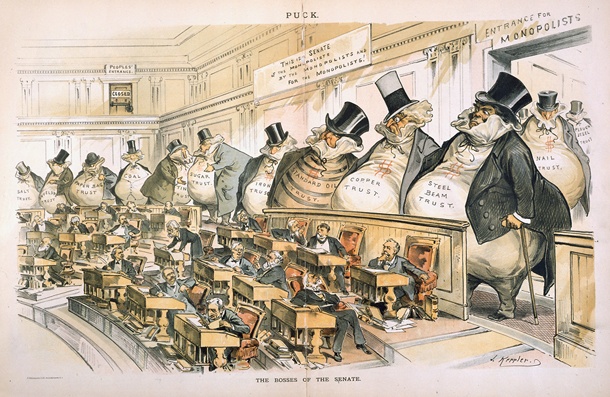

This 1889 cartoon by Joseph Keppler shows big business monopolies sitting in he US senate under a plaque stating “This is the Senate of the Monopolists by the Monopolists and for the Monopolists!” President Theodore Roosevelt took on the monopolies with antitrust legislation. Credit: Wikimedia

As a general rule, if you can name all the big players in a market, or even just count them, there’s something wrong with that market. References to a “Big Six” or a “Big Four” or some other small number should be a warning sign.

That’s because when there are relatively few big players in a market, companies that serve most of the customers in that market, there’s a risk that they don’t have to compete as fiercely as they should to keep their customers and win new ones. That means higher prices, worse service, less innovative products for households. For the economy more widely, it means underinvestment in the productive capacity that drives higher growth and higher wages.

Together, those things leave many people feeling ripped off, ticked off, and wondering if the system really is rigged against them.

At the Social Market Foundation, we have investigated the markets that matter most for voters’ experience of the market economy, those focused on consumers, which collectively account for about 40% of all consumer spending – cars, groceries, broadband, mobile telephony, landline-only phone contracts, electricity, gas, personal current accounts, credit cards and mortgages.

Sadly, we found that people’s suspicions of a rigged model are justified. Most of those markets aren’t working as well as they should. Eight of the ten are concentrated, a large proportion of sales made by a small number of suppliers. Only the markets for cars and mortgages meet the description most people would have of a free and competitive model.

We also identified a link between higher levels of market concentration and lower levels of customer service and trust. That’s understandable when you consider the way people are treated.

The pricing policies of the Big Six energy companies make it all too easy for critics of the industry to accuse firms of cynically exploiting consumers’ inertia and limited information: attractive “teaser rates” draw in new customers then mysteriously vanish, meaning many customers drift unwittingly into higher tariffs.

One of the worst practices in concentrated markets is bundling, where dominant players can offer what appear to be attractive and convenient deals to supply several goods and services together, for instance pay TV, broadband and a landline. Such deals are often expensive and unfair on customers, who cannot easily tell how much they pay for individual items – which may well be available more cheaply elsewhere.

The best remedy for harmful concentration is, of course, competition. When new challengers enter the market and fight incumbents for their customers, those customers tend to get a better deal. The UK supermarket sector today offers better deals to customers than it did a decade ago partly because of the entry into the market of chains such as Aldi and Lidl. Anyone who wants to save the market from the populists who would replace it with state control needs to think about ways to help challenger companies put big incumbents under more pressure. Competition that makes incumbents feel less comfortable is good for customers, and good for faith in markets.

Of course, we have rules and laws and public bodies who are responsible for doing this. But frankly, right now regulators and competition authorities are struggling to put up a fight on behalf of consumers.

One aspect of concentrated power in consumer industries I find most troubling is the ease with which big, rich incumbents can capture or defeat the regulators who are supposed to watch over them and ensure their market is delivering fairly for consumers.

A lot of this is about financial muscle, plain and simple. Big companies making big profits can afford to fight and win against regulators with more limited resources. One senior regulator puts it this way:

“Whatever decision we make, they can appeal, and if we have two lawyers on the appeal, they have ten. And if our lawyers are still good enough to win, they’ll get a job offer in the private sector soon enough and end up working for a regulated company.”

Some of the antics alleged in regulated industries are frankly scandalous. One telecoms executive recently told me about a rival firm that successfully gamed Ofcom’s broadband speed testing by simply cutting off a large number of rural customers with slow connections during the testing period.

I don’t say this as criticism of the regulators themselves, so much as criticism of the politicians who give the regulators their remit and their resources. Sometimes those remits simply don’t allow adequate intervention to prevent the concentration of market power that could harm consumers.

It’s an open secret that some senior officials at the Competition and Markets Authority were deeply uncomfortable about the authority’s decision in 2016 to allow BT to take over EE. The £12.5 billion deal brought together the UK’s largest fixed telecoms business and the UK’s largest mobile telecoms business. Despite widespread worries that the deal would harm consumers, the CMA’s own rulebook meant the authority had to give it the green light.

That’s one of the challenges about competition, concentration and consumers that politicians should be trying harder to meet. Other, bigger questions include what Britain’s competition regime will look like after Brexit, and how it can be designed and equipped to deliver the best deal for consumers.

Sadly, there’s not much enthusiasm for answering such questions right now, even though the task becomes more urgent by the day.

Yet it’s noticeable how little politicians, policymakers and experts in Britain have paid attention to it. American economic debate is heavy with analysis of concentration ratios, incumbent advantage and the prospect of dramatic “antitrust” state intervention.

That’s partly a question of history: the antitrust movement of the early 20th Century, when big oligopolistic incumbents (then known as “trusts”) such as Standard Oil were broken up, still loom large in the American political imagination.

That history is getting a lot of attention in US political circles again now.[1. Maurice Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi, ‘The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of the U.S. Antitrust Movement’, Harvard Business Review, 15 December 2017] A group of economists and lawyers sometimes called the New Brandeis movement is asking all the right questions about the power of big incumbents in the markets that matters most to consumers and voters.

Anyone who wants to save Britain’s open market economy from the populists who would sweep it away needs to reflect on the lessons from thinkers like Louis Brandeis.

That might – or might not – mean the state intervening to break up big companies, but it should definitely mean that same state taking a much more active role to make sure those companies have to work harder.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe