2012 London Paralympics (Photo by Mike Ehrmann/Getty Images)

This is the fourth in a series of articles looking at people, places, institutions or subject areas that the news media does not serve well. Once the series is complete, we’ll be polling UnHerd subscribers – asking which UnHerd author they most agree with.

Twenty five years ago, I entered the twilight world of parents with children with special needs. My beautiful daughter was born with a rare genetic condition, CDKL5, that leaves her unable to communicate with words, see, walk or live independently. She needs 24-hour care to help support her complex epilepsy.

I thought I was on my own before the advent of the internet, with no support network. I did not realise that I was among the hundreds of thousands of parents in the UK who have a child with special needs, as almost all were out of sight and out of mind. Shockingly, I was told by some well-meaning people it would be better to put her in a home and forget about her.

This is changing but progress is slow. People with disabilities are appearing in adverts such as the latest McCains ad or in television programmes like Call the Midwife, but these are the exceptions rather than the rule. In news, the narrative is closely focused in three ways.

There are the extreme stories. The shock at the abuse at Winterbourne View; or the despair when a young man dies in a bath in an NHS Treatment and Assessment Unit, in Oxford; or the horror when a mother takes her life and that of her autistic child after she jumps off a suspension bridge. Once the initial furore is over, the fight for justice and change is often a battle left again to families.

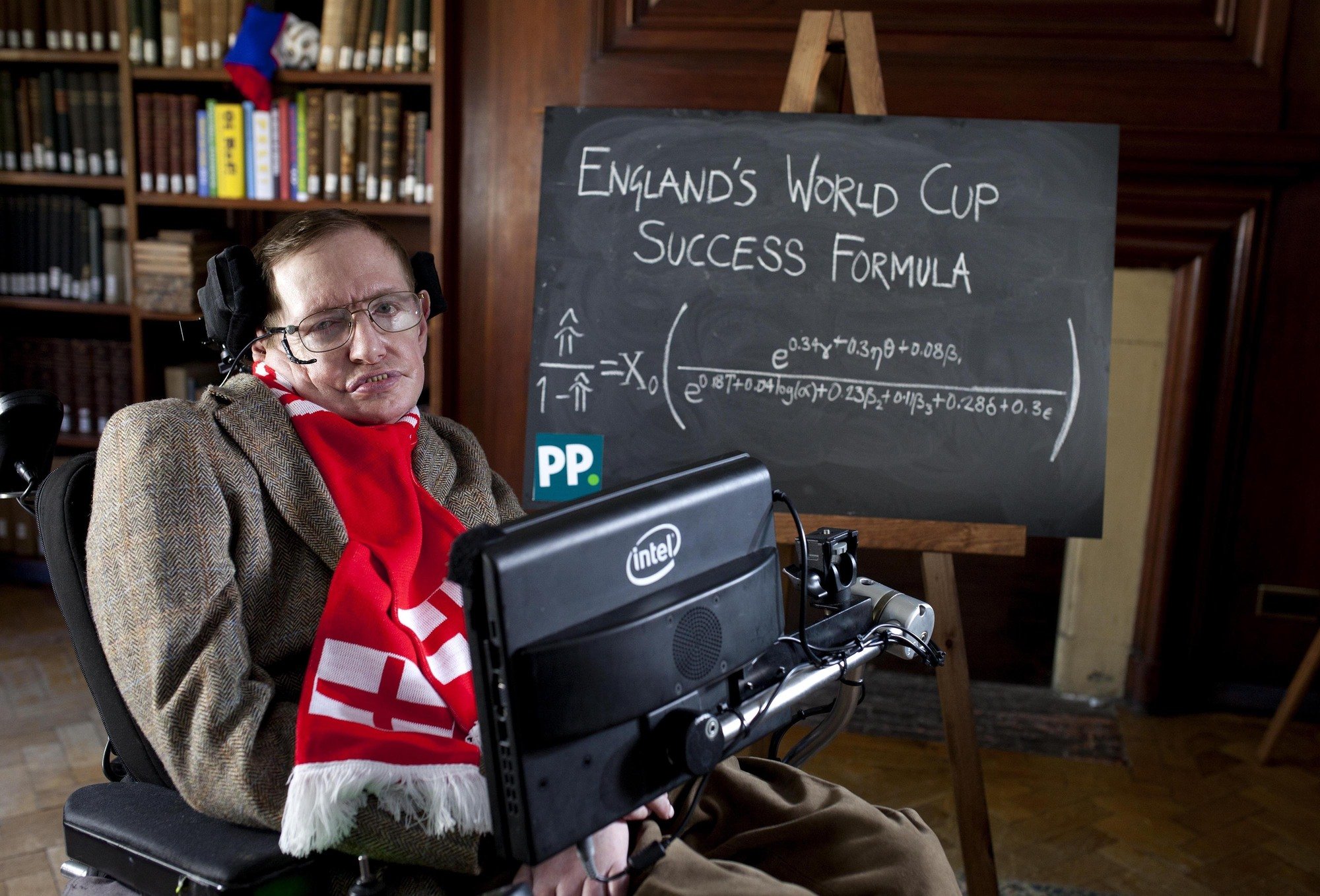

Then there are the stories of heroics. This week, the media celebrates the work of Stephen Hawking, that brilliant scientist, and focuses on how this was achieved despite his ‘desperate disability’, while almost every other person living in Britain with ‘desperate disability’ goes unnoticed.

And, lastly, there are the scroungers. The supposed parasites who live off the state, rip off the state and give nothing back seen fleetingly in headlines.

Rarely, though, do I read stories I recognise – stories concerning people like my family, and all those others I meet. The everyday lives of ordinary people do not make great headlines, which is why the lives of people with special needs and their families go largely untold, unseen and unrecognised. And this is a problem.

At a recent meeting discussing “transition”, the intensely stressful period when young people move from children’s services into adult services, a third of the parents attending were in tears. They were learning there was no future for their child: no supported housing, no further education, no jobs and no support. Child services may be minimal, but adult services are almost non existent particularly for those with more moderate disabilities.

Nowhere is this reported.

And so the fact that nearly a third of those in prison have a learning disability or difficulty goes unnoticed. So too does the fact that large employers, including local authorities and charities, fail to keep records of how many people with disabilities they employ, even as they ask others to make workforce accommodations. Who talks about the fact that the vital role played by the paediatrician suddenly halts at 18, and that no one oversees adult health? And what about how the money spent on bureaucracy is continually rising, while frontline services suffer?

There are seven million carers like me in Britain, an invisible taskforce taking so much strain off the state. Did you know that carer’s allowance is set at £62.70 for a minimum 35 hour week? And if a carer earns more than £116 a week, they lose that? Does anyone write about how carers are usually on call 24 hours a day? That their days leave them broken, exhausted and beaten till they themselves are in need of care.

As a nation, we do not invite people with disabilities to our homes. We do not meet them in our workplaces. The tragedy is we do not really know them.

And because this reality is not recounted, the pockets of good practice – which if shared would raise hope and expectations for people with special needs – go unnoticed. So local arts groups working in a truly integrative way are uncommended. But I could tell you about Access All Areas, with projects like Spinning Wheel, in which people such as my daughter are seen as a vital part of the performance. Or there are the social evenings hosted by parents at Shoot Up Hill, north London, where families gather to share a meal around a table with their adult children.

There are the cafes and the industries like Harry Specters, a wonderful chocolate company, set up by parents who otherwise could not see a future for their son or daughter. There are also employment schemes such as ProjectSEARCH, through which young people with learning difficulties spend a year working in hospitals and hopefully graduate into employment. But these are uncelebrated.

Mainstream media need to pick up on issues that families of children with special needs have been shouting about on social media for some time. For by ignoring these stories all our futures are damaged.

By embracing the world of disability and recognising the value of a perspective often untrammelled by normative behaviour we can find out things about ourselves that maybe we didn’t want to know. Perhaps we will realise that many of those things we strive for aren’t quite so important after all. It’s time our stories were heard.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe