The world of cartographers Gall-Peter is characterised by all land and sea enjoying the same share of the mapped/ illustrated space. The result is a much bigger-looking Africa when compared with more familiar projections, notably Mercator.

This is the second part of a series looking at people, places, institutions or subject areas that the news media does not serve well. Tom Chivers looked at science yesterday. Once the series is complete we’ll be polling subscribers to UnHerd’s free mailing list – asking which UnHerd author they most agree with.

“If I have to tell people where it is, Katie, it’s not going in the paper,” a British tabloid news editor told me, when I was working in communications for an international NGO.

We were talking about Mali.

To be fair, it was back in 2012, before the French had sent in troops, the big international hotel in capital city Bamako had been raided, or footballer Kante had signed with Chelsea.

There was an ongoing food crisis, driven by climate change, rumbling conflict, and alarming levels of movement of people: all the indicators that competent international development practitioners recognise as warnings of imminent humanitarian crisis. I had stories I wanted to pitch, which I reckoned were useful, interesting and prescient.

But my contact made an important point.

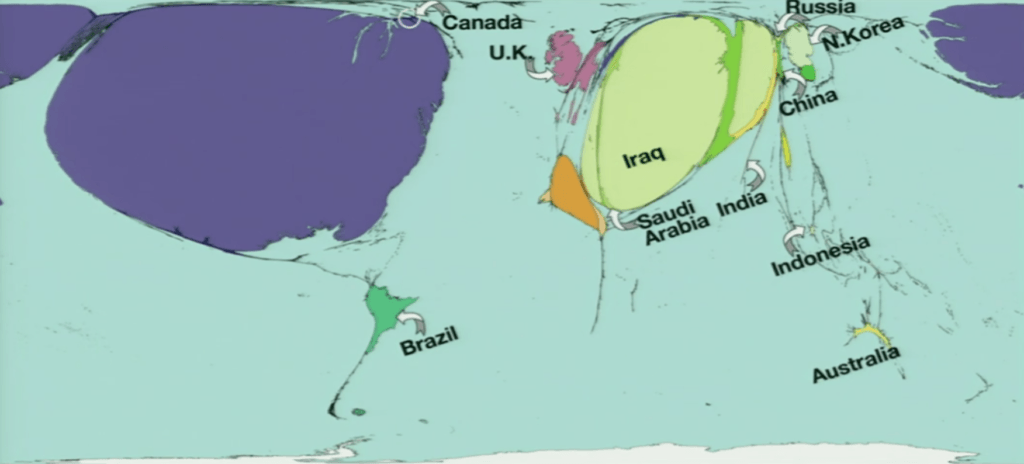

When it comes to Africa, or other less economically developed parts of the world, western countries only tend to cover their news when we ‘know where it is’.

Especially when it comes to a slow onset situation. Seeing what’s coming doesn’t qualify as ‘news’ in a media regime which prioritises the new and (sometimes) urgent over the important. Early warning signs are not enough: humanitarian workers have to watch more and more children die before the world pays attention[1. Although aid charities aren’t entirely innocent when it comes to fully-fair, full-pictured coverage of many African nations and other parts of the world that find themselves in short or long-term need – see my recent piece on NGOs’ misrepresentation of our winning battle against global poverty.]. Look at South Sudan.

How do we ‘know where it is’?

My tabloid friend was right. Brits didn’t know about Mali (notwithstanding Roger Hargreaves’ children’s stories with characters based in Timbuctoo). Why would we? They speak French there, drive on the wrong side of the road, and we don’t visit for safari holidays or gap year backpacking.

Because that’s what it comes down to. If you’re like me and take the opportunity when travelling to brush up school days French by watching TV5 in the hotel room, you’ll notice that its international coverage is distinctly different to what you’d see in the UK. They cover West Africa, while British media is more likely to mention – if at all – countries in East or Southern Africa with which we have a historical connection.

The countries which used to ‘belong’ to us remain interesting. Not necessarily from intentional colonial hangover but because our grandparents might have been posted there, our student nephews and nieces volunteer there and, if they’ve developed a tourism industry, we might have taken a second honeymoon there. We know the (official) language, our electrical plugs fit, we’ve remembered a bit about them from school history lessons. US think tank Brookings found the same phenomenon in US coverage: South Africa media reporting tends to fall into ‘before Mandela’, ‘during Mandela’ and ‘after Mandela’ because he was the statesman with whom Americans had a level of connection.

It’s all very middle class, but there it is. We follow stories which are sufficiently different from our own lives to qualify as ‘news’ while being sufficiently familiar for us to identify with the story. So we don’t notice some of the world’s major emergencies because they’re not close enough to our worlds.

One at a time, folks…

A few years ago, I was in Central African Republic interviewing rape survivors in the middle of the messy and extremely violent conflict. We quickly had to leave a camp site of displaced people in the grounds of a church when security alert came through. Minutes later there was a drive-by shooting and some of the people we had just been interviewing were killed.

In the following hours, as the already chaotic city went into lockdown, I rang some journalist friends. They worked on globally respected broadsheet newspapers and knew the beat far better than I did. One in particular was hugely sympathetic, asked insightful questions but ended up confessing that “I’ll have to check with my editor. We can only make room for one Africa story a day, and it’s the Pistorius trial this week.”

For the most part, ‘Africa’ is a news category in itself. As we see from the frustrations expressed by the campaign team behind #AfricaIsACountry which both pokes fun at the way we lump stories together, and offers writing and comment from emerging voices, we have created a genre of its own. In developed countries, we tend to treat the entire continent – or the sub Saharan element, at least – as a homogeneous mass, ignoring massive economic, trade, humanitarian, diplomatic, culture, crime and political differences.

It’s all part of the ‘international’ section

Ruth Maclean covers West Africa for the Guardian, and previously had an Africa brief for the Times of London. Investment manager Ory Okolloh Mwangi tweets business and other news stories. Tom Murphy is an independent journalist covering global humanitarian stories. Follow IRIN News for comprehensive humanitarian news and analysis. Geoffrey York covers Africa for the Globe and Mail. And for an up-to-the-minute daily round up of news from around the world, especially developing countries, sign up for www.dawnsdigest.com.

In my experience, it’s hard to get a comment piece about somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa into a British broadsheet when they’re already carrying an op-ed about Ukraine (yes, I know – not in Africa but ‘foreign’!). The International Broadcasting Trust analysed UK broadcast news coverage for two weeks in January 2016, and compared levels of coverage of events outside the UK with a previous study from 2009. They found that international coverage had increase BUT in those two weeks the focus was on Hollywood’s Oscars, refugees arriving in Europe from the Middle East and the closure of the port of Calais. But the number of countries covered was down from previously:

“Despite the increase in coverage since the 2009 study, driven in part by audience demand, certain areas of the world remain relatively under-represented. Excluding the bulletins of Al Jazeera English and BBC World Service, fewer countries were featured than in 2009 and most of the increase was accounted for by stories from Europe.”

It’s out there somewhere – often online

To be fair, most of the bleating we see on social media, when enthusiastic campaigners worry ‘why is no-one covering this?’, is accompanied by a news report posted online by the BBC or Reuters. Nonetheless, the news bulletins on mainstream TV, and the print editions of newspapers (falling in number as advertising revenues shrink) are necessarily and increasingly limited for space. But online? It’s usually covered somewhere and determined Africa-watchers can find it. I’ve pasted the Twitter addresses of some insightful, trustworthy journalists in the sidebox.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe