E-government naturally favours the young (Photo: Mark Kolbe/Getty Images)

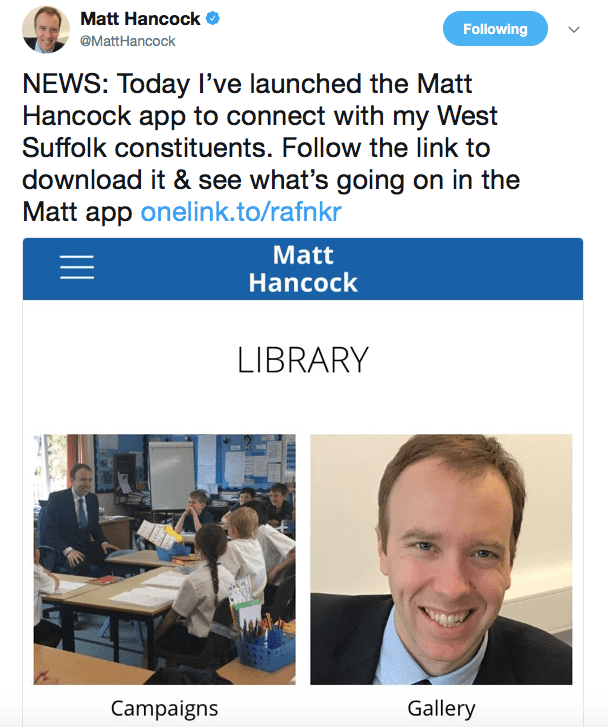

The recent launch of the app from the British Minister for the Digital Economy – which allows anyone who downloads it to connect up with the West Suffolk MP – was greeted with some ridicule. But while those sniggering may have noticed certain privacy issues, they obviously hadn’t grasped its greater importance. In fact, Matthew Hancock’s new social media service was reflecting a digital approach that had been some ten years in the making.

Hancock had set out his stall a couple of years earlier in a speech to the CPS[1. ‘Supporting the disruptors and the disrupted: Harnessing technology for all‘. The 2016 Keith Joseph Memorial Lecture]. Contemporary politics, he said, was split between left-wing reactionaries, such as Corbyn and Bernie Sanders, and right-wing reactionaries, a la Farage and Trump; both “obsessed with recreating a better yesterday” and both seeking “false certainties” that are no longer there. But the future, he said, for his party and for global capitalism lay in an unflinching investment in technology and the culture of disruption emanating out of California.

Hancock’s intense optimism in the digital revolution placed him among a new breed of British politician, the ‘Uber Cons’, who recognised in the digital revolution the potential for Conservative principles to be realised once more. These ‘UberCons’ were libertarian in economics, metropolitan in values and embraced a form of globalisation which is not burdened with old imperial guilt or even eurosceptism – and they were obsessed with emerging markets and restoring Britain’s innovative tradition.

Their rise dates to George Osborne’s pilgrimage to Silicon Valley, in 2006, from which he reported excitedly:

I have seen the future and at present Britain is not part of it…. we may have invented the internet but it’s the Americans who have colonised it. It’s time to stake our claim.

Osborne was true to his statement. And his tech strategy has been a great success; comparable in scale and speed to Thatcher’s deregulation of the City of London in the eighties. Digital is now worth 7% of the UK economy and is growing at a much faster rate than the rest of it.

But an equally significant part of the story was how Silicon Valley thinking could disrupt the British state and public services. A thriving digital economy and the development of e-government could reduce public expenditure and extend consumer choice and responsibility. Likewise, it was hoped that embracing flexible working models (unbeholden to unions) and the sharing economy would enable the twin pillars of Conservatism – entrepreneurialism and voluntary spirit – to thrive.

The mantra, taken from Stanford’s philosophy of human-centred design, would later be the title of a book by Steve Hilton, one of the original UberCons. The creators behind gov.uk reflected a new breed of civil servant: less “man in Whitehall knows best”, more “man in Whitehall could do cool stuff with code”. In fact the offices were based in Waterloo and had the feel of an endless hackathon, manned not by Sir Humphrey-types but by self-identified ‘disruptors’ donned in the Californian-uniform of jeans and trainers.

The Government boasted it had saved £1.7 bllion through digital transformation and sold the code to other countries such as New Zealand looking to do the same thing. In 2015 Cameron described the creation of the Government Digital Service as “one of the great unsung triumphs of the last Parliament”. The following year, the UK topped the rankings in the UN’s global e-government survey.

UberCons embraced digital disruption with the same enthusiasm that their Conservative forebears embraced monetarism in the 1970s. Back then, neo-liberals took inspiration from economists at the University of Chicago for the miracle M4 formula to control the money supply and inflation. The new breed of 21st century Conservatives looked instead to techies at Stanford for algorithms to reduce the size of the state and fix a broken market.

Someone once said that Silicon Valley runs on solving one problem: ‘What is my mother no longer doing for me?’ The hope was that digitisation could also solve one intractable problem: what can the bureaucratic state no longer afford to do for its citizens?

The answer was simple: citizens were now online and mobile, so the state must be, too. It must be smarter, nimbler, more responsive, accessible and of course, smaller. If a company like Whatsapp only needed 50 engineers for its 900 million users, why did the government need to employ so many people?

And a bold and all-encompassing process of generating ‘the contactless state’ was launched, along with the hope that the government’s plans for digitalisation will be its global success story, like privatisation was for Thatcher in the 1980s.

But then the European referendum turned the focus of the state upside down. The UberCons lost their patrons in Downing Street and the machinery of government froze in preemption of the Brexit negotiations.

No one in the tech industry saw a natural ally in Theresa May. The referendum, and the political fallout since, has signalled a new political era and a new conversation, chiefly about the gaping divide (in David Goodhart’s words[2. David Goodhart, The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics, 17 March, 2017]) between citizens from ‘somewhere’ and those global citizens from ‘anywhere’. The latter were, fairly or otherwise, associated with metropolitan-tech values and an obsession with progress and disruption. And they were out of favour. May’s premiership also coincided with a more critical questioning of Silicon Valley ethics, be it dubious tax affairs, latent sexism, concerns over data and national security, or its failure to tackle fake news.

For all its talk of disruption, it was clear that the tech industry had matured into a set of global conglomerates much like any other; dominated by huge uncompetitive entities which have aped the corporatist culture they originally pledged to overthrow.

But while the political context is different, the progress towards a paperless state has continued.

- In 2017, the Government Transformation Strategy was announced, a year later than scheduled, with a promise to create a Digital Academy to train civil servants to ‘think in code’ and to launch public services further into the cloud.

- The Tories committed to creating the most “comprehensive geospatial data body and the largest repository of open land data in the world” which it hopes will digitise the planning process and allow virtual mapping of the UK for use in anything from military exercises to video games.

- The DCMS had a digital rebrand, acknowledging the fact that half of its policy work now covers the tech sector

This ambition has not been without hiccups. The Government’s identity system, Verify, proved insufficient in 2014 when farmers, who invariably lived in areas with poor broadband reach, were unable to log on to apply for their EU grants. Local councils are seriously lagging behind in e-government – with the odd exception, such as Enfield in North London, which uses robot technology to deal with frontline issues – while the ambition for a truly digital NHS seems a distant dream and a potential nightmare given the cyber attack last May.

E-government of course favours the young, those that live in cities and the computer literate. With 23% of the UK adult population – 12.5 million – without sufficient digital skills and in a country whose broadband coverage is far from comprehensive digitalisation risks alienating a significant number of citizens. We could end up replacing the current post-code lottery of public services with a two-tier service, where those who are able to do things digitally get a better service.

Costly call centres and administrative staff will be replaced with chatbots happy to communicate in any language and deal with any enquiry from benefit claims to medical prescriptions to tax returns. E-government utopia is one in which data analytics will make policies entirely responsive; where government is able to tweak services in hours not months and at negligible cost. And where nothing is hidden: our lives and our vulnerabilities are quantified and set down in the frictionless system.

So what is going on? Are we happily seeing off the ‘computer says no’ state? Or are we ushering in George Orwell’s 1984?

Regardless of our fears, digital disruption is fundamentally changing society and government. It can’t be ignored. Unless, of course, you’re in Britain’s Labour party. Jeremy Corbyn was the crowd-sourced king – a product, like Trump, of click activism, like Trump Corbyn has shown little sense of an understanding of technology and its ramifications beyond political self-interest.

Brexit may have halted the rise of UberConservatism as a dynamic political philosophy, but given that the British state is about to undergo its greatest reform since the Second World War, the disruption is only just beginning. For politicians, the focus must be on who it leaves behind, as much as anything else.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe