Credit: Wikipedia

In the first entry to our ‘Free Minds’ series, Nigel Cameron profiles Sherry Turkle.

When you stop by her office at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sherry Turkle, Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology, doesn’t wave you to a seat in front of a mahogany professorial desk. She offers you your choice of her comfy couches (and, at least in my case, she offers you coffee). For she isn’t simply a sociologist and ethnographer and anthropologist. She’s also a psychologist and psychoanalyst. And while much of her life has been devoted to studying digital technology, her first book was actually about Sigmund Freud. If ever we mere humans needed an advocate in the face of the technological-industrial complex and its devices, we’d hope for someone like her.

1984: Orwell, Turkle, Zuckerberg

There were a mere ten million computers in the entire United States when Sherry Turkle, already a professor at MIT, staked her claim to be the champion of human questions in the dawning digital era. Back in that haunting year, 1984. Back before any one of the companies that dominate today’s internet had yet been heard of. Even before Tim Berners-Lee had come up with the World Wide Web. Somewhat curiously, it was also the year Mark Zuckerberg was born.

In her prescient book The Second Self, she reviewed the rapid spread of what she called the “computer culture,” and reflected that – even then – “in one way or another” it “touches us all.” Grasping in a single phrase what many would come to see as the core question of the 21st century, she subtitles the volume “Computers and the Human Spirit.”

In her prescient book The Second Self, she reviewed the rapid spread of what she called the “computer culture,” and reflected that – even then – “in one way or another” it “touches us all.” Grasping in a single phrase what many would come to see as the core question of the 21st century, she subtitles the volume “Computers and the Human Spirit.”

Reading The Second Self a generation later is an eerie experience.

Take children, for example.

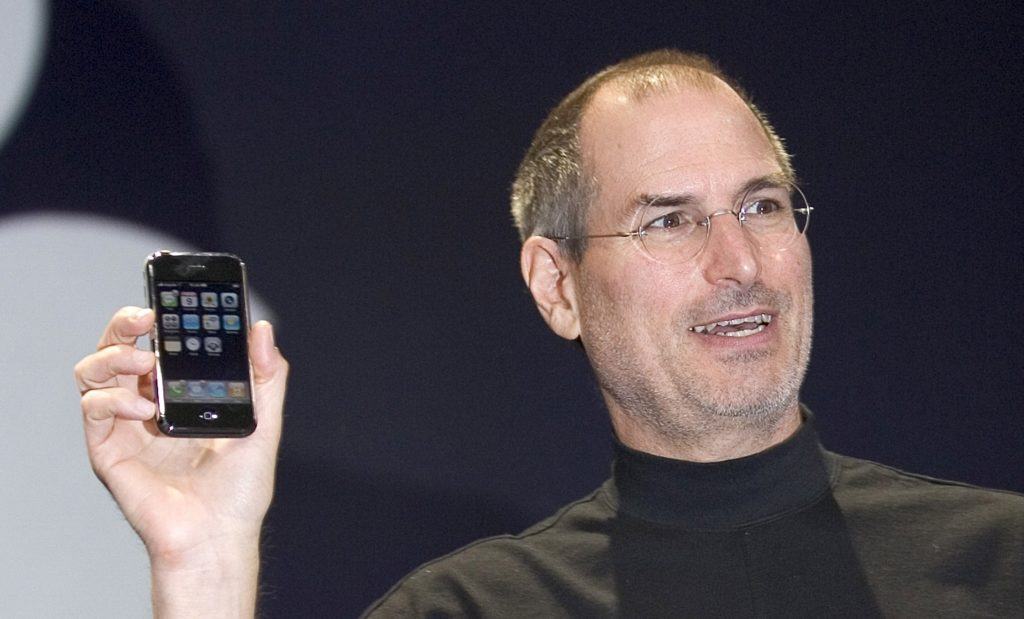

Long, long before Mark Zuckerberg launched Messenger Kids to bring six-year-olds into Facebook, before Mattel launched Hello Barbie, their chatty robot doll, Sherry Turkle was studying “children’s relationships with computers.”

“I found three stages …. First there is a “metaphysical” stage: when very young children meet computers they are concerned with whether the machines think, feel, are alive. Older children, from age seven or eight on, are less concerned with speculating about the nature of the world than with mastering it.” And in adolescence “computers become part of a return to reflection, this time not about the machine but about oneself.”

What distinguishes Turkle’s work from so much commentary on the rise of the digital world is its basis in research. Her observations are rooted in something other than opinion and anecdote. “This work is a field study based on many thousands of hours of interviews and observations,” she writes.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe