Credit: Wikipedia

In the first entry to our ‘Free Minds’ series, Nigel Cameron profiles Sherry Turkle.

When you stop by her office at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sherry Turkle, Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology, doesn’t wave you to a seat in front of a mahogany professorial desk. She offers you your choice of her comfy couches (and, at least in my case, she offers you coffee). For she isn’t simply a sociologist and ethnographer and anthropologist. She’s also a psychologist and psychoanalyst. And while much of her life has been devoted to studying digital technology, her first book was actually about Sigmund Freud. If ever we mere humans needed an advocate in the face of the technological-industrial complex and its devices, we’d hope for someone like her.

1984: Orwell, Turkle, Zuckerberg

There were a mere ten million computers in the entire United States when Sherry Turkle, already a professor at MIT, staked her claim to be the champion of human questions in the dawning digital era. Back in that haunting year, 1984. Back before any one of the companies that dominate today’s internet had yet been heard of. Even before Tim Berners-Lee had come up with the World Wide Web. Somewhat curiously, it was also the year Mark Zuckerberg was born.

In her prescient book The Second Self, she reviewed the rapid spread of what she called the “computer culture,” and reflected that – even then – “in one way or another” it “touches us all.” Grasping in a single phrase what many would come to see as the core question of the 21st century, she subtitles the volume “Computers and the Human Spirit.”

In her prescient book The Second Self, she reviewed the rapid spread of what she called the “computer culture,” and reflected that – even then – “in one way or another” it “touches us all.” Grasping in a single phrase what many would come to see as the core question of the 21st century, she subtitles the volume “Computers and the Human Spirit.”

Reading The Second Self a generation later is an eerie experience.

Take children, for example.

Long, long before Mark Zuckerberg launched Messenger Kids to bring six-year-olds into Facebook, before Mattel launched Hello Barbie, their chatty robot doll, Sherry Turkle was studying “children’s relationships with computers.”

“I found three stages …. First there is a “metaphysical” stage: when very young children meet computers they are concerned with whether the machines think, feel, are alive. Older children, from age seven or eight on, are less concerned with speculating about the nature of the world than with mastering it.” And in adolescence “computers become part of a return to reflection, this time not about the machine but about oneself.”

What distinguishes Turkle’s work from so much commentary on the rise of the digital world is its basis in research. Her observations are rooted in something other than opinion and anecdote. “This work is a field study based on many thousands of hours of interviews and observations,” she writes.

And she’s continued asking questions about the digital revolution and the human spirit ever since – and seeking answers grounded in sober facts and analysis.

Let’s talk

As Carlos Lozada in the Washington Post notes in reviewing her latest book[1. From “The book that will have everyone talking about how we never talk anymore her latest book”, Washington Post, 1 October 2015: “We think our devices deliver comfort and efficiency, but, in Turkle’s telling, they offer loneliness and disarray. “Every time you check your phone in company,” she reminds, “what you gain is a hit of stimulation, a neurochemical shot, and what you lose is what a friend, teacher, parent, lover, or co-worker just said, meant, felt.””], Reclaiming Conversation, it would be a mistake to lump it together with the stream of “tech-skeptic manifestos.” “This is a persuasive and intimate book,” he writes, “one that explores the minutiae of human relationships. Turkle uses our experiences to shame us, showing how, phones in hand, we turn away from our children, friends and co-workers, even from ourselves.”

The situation is one familiar to all of us. In Lozada’s summary:

“You’re at the dinner table, or in a meeting, or at a baseball game, or in the classroom, or in your bedroom, or at a bar or, yes, in the bathroom — and you’re on your phone. You might be talking, but more likely you’re texting, posting, swiping, liking, tweeting, buying, browsing or, in my favorite metaphor of digital existence, “refreshing,” as though life’s staleness can be washed away with every new, fully realized screen.”

A super-abundance of conversation, surely!

And yet:

“This is the world of incessant connection, and for all the communication it supposedly provides, it’s destroying one essential thing: open-ended conversation. “We are being silenced by our technologies,” Sherry Turkle warns, “in a way, ‘cured of talking.’” And that silence means our ability to relate to others is disappearing, too. “We face a flight from conversation that is also a flight from self-reflection, empathy, and mentorship.”

Three strikes…

While Sherry Turkle’s early work focused on humans and on computers that actually looked like computers, the context today can be summed up as the conjunction of three factors:

- First, the basic inter-connectedness of the internet, which was dramatically enhanced by the invention of the Web (1991);

- Second, the development of social media (Facebook was founded in 2004, though AOL, 1985, and MySpace, 2003, were the pioneers);

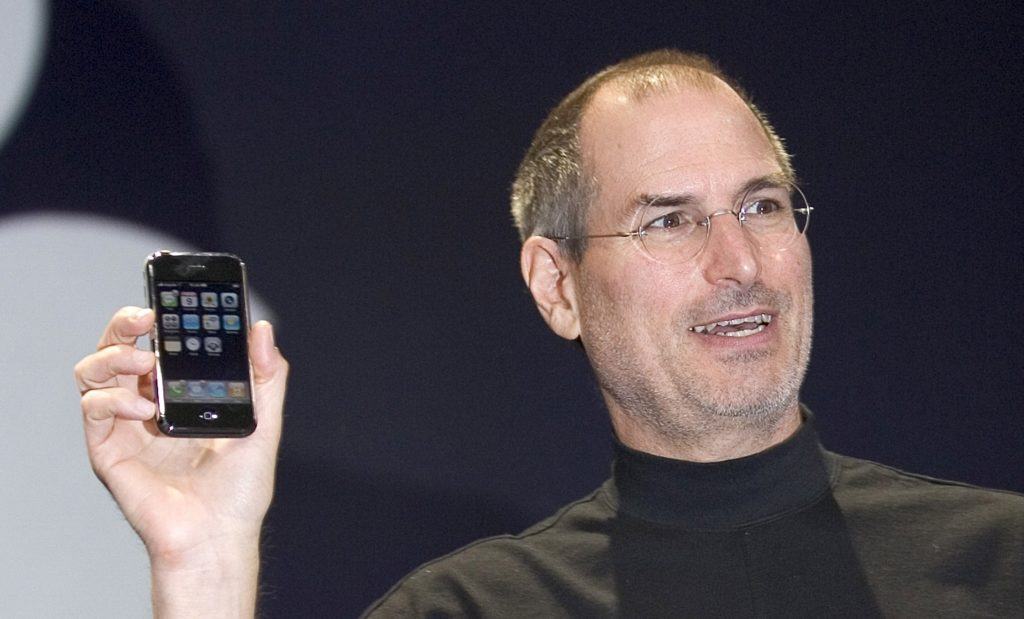

- And, third, the near-miraculously explosive deployment of smartphones (iPhone: 2007), putting super-computers into our hands and pockets.

We have become so used to these little devices. It is sobering to be reminded of the impact of “Moore’s Law” – the principle that computer power keeps doubling as the price drops. The numbers are truly astonishing. In the past sixty years, computing power has increased by a factor of one trillion. An iPhone 4, if you can still find one, has the same power as the Cray super-computer of 1985[2. Read Maddie Stone on The trillion-fold increase in computing power, visualized].

It is these technical developments that have created today’s social media/smartphone challenge.

For great and small, we members of Homo sapiens are rarely far from our smartphones. The single most startling story of the digital revolution is the staggering speed with which the “mobile device” has spread into the hands of billions.

A decade after the launch of the iPhone in 2007, the numbers are stunning. According to a recent Pew study[3. Among ten findings about smartphones by Pew: “Overall, 12% of U.S. adults were “smartphone-only” internet users in 2016 – meaning they owned a smartphone but did not have broadband internet at home.”], in the United States three-quarters of adults own a smartphone – including 64% of those living in a household with an income of less than $30,000. Half of young adults live in a household that owns three or more of them. As smartphones get cheaper, their global spread continues. One projection is for six billion to be in circulation by the year 2020.

Real life

- Haley, who is seeking to console her friend Natalie at a time of personal loss. But as she sits next to her, Natalie is too busy seeking consolation from “the people on the phone” to notice her friend.

- Danny is 32. He flirted with other women even though he was on the verge of committing to a young woman he was fond of; he thought he could do better. She found out and called it off. Turkle notes that people enjoy chocolates more if they choose them from a small rather than a big box.

- Adam, a professional in his 30s, broke up with a girlfriend but is haunted by the digital record he still has. He shows Turkle his old phone. Because he can’t work out how to do it automatically, he has been transcribing the 1,000 texts they exchanged.

- A teen girl really wishes she could talk with her mother. Her mother bans phones from dinner, but breaks her own rule “because it’s work.” The teen keeps trying to get onto conversation, but fails. And a fact we may all find surprising.

- If there’s a smartphone on the table, even if it is turned off and everyone knows that, its presence will re-shape the conversation.

Over the years, Sherry Turkle has deployed her incessant questioning on several fronts. She has written about simulations, about our capacity to adopt alternative personalities online, about the loneliness that bizarrely can so easily be the concomitant of our endless engagement in digital communication. But it’s here, in her beguiling advocacy of conversation – packed with telling observations and haunting incidents – that her campaign for the human spirit comes to a head. In the words of novelist Jonathan Franzen, she “serves as a kind of conscience for the tech world.”

And in a remarkable tribute, technology icon Kevin Kelly, founding editor of Wired magazine and as far from being a Luddite as one can get, has this to say:

“Smartphones are the new sugar and fat: They are so potent they can undo us if we don’t limit them. Sherry Turkle introduces a lifesaving principle for the twenty-first century: face-to-face conversation first. This heuristic really works; your life, your family life, your work life will all be better. Turkle offers a thousand beautifully written arguments for why you should lift up your eyes from the screen.”

The bottom line

“Why a book on conversation?” asks Sherry Turkle. “We’re talking all the time. We text and post and chat…. Among family and friends, among colleagues and lovers, we turn to our phones instead of each other.”

She begins her book with a quote from Thoreau’s Walden: “I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.”

It actually ends, on the back cover, with a review from the Boston Globe: “Talk is cheap, but conversation is priceless.”

***

MORE ON TURKLE, MORE BY TURKLE

FROM TED TALKS, 2012

As we expect more from technology, do we expect less from each other? Sherry Turkle studies how our devices and online personas are redefining human connection and communication — and asks us to think deeply about the new kinds of connection we want to have.

“We are shaped by our tools.” – Alone Together

“When we let our minds wander, we set our brains free. Our brains are most productive when there is no demand that they be reactive.” – Alone Together

“Every time you check your phone in company, what you gain is a hit of stimulation, a neurochemical shot, and what you lose is what a friend, teacher, parent, lover, or co-worker just said, meant, felt.” – Reclaiming Conversation

“We fill our days with ongoing connection, denying ourselves time to think and dream.” – Alone Together

“Because you can text while doing something else, texting does not seem to take time but to give you time. This is more than welcome; it is magical.” – Alone Together

“In order to feel more, and to feel more like ourselves, we connect. But in our rush to connect, we flee solitude. In time, our ability to be separate and gather ourselves is diminished. – Reclaiming Conversation

“But if we don’t have experience with solitude—and this is often the case today—we start to equate loneliness and solitude. This reflects the impoverishment of our experience. If we don’t know the satisfactions of solitude, we only know the panic of loneliness.” – Reclaiming Conversation

“If behind popular fascination with Freudian theory there was a nervous, often guilty preoccupation with the self as sexual, behind increasing interest in computational interpretations of mind is an equally nervous preoccupation with the self as machine.” – Alone Together

“Technology proposes itself as the architect of our intimacies.” – Alone Together

“This is the experience of living full time on the Net, newly free in some ways, newly yoked in others. We are all cyborgs now.” – Alone Together

“To understand desire, one needs language and flesh.” – Alone Together

“Swaddled in our favorites, we missed out on what was in our peripheral vision.” – Alone Together

“Whenever one has time to write, edit, and delete, there is room for performance.” – Alone Together

“We have testimony about solitude from the most creative among us. For Mozart, “When I am, as it were, completely myself, entirely alone, and of good cheer — say, traveling in a carriage or walking after a good meal or during the night when I cannot sleep — it is on such occasions that my ideas flow best and most abundantly.” For Kafka, “You need not leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. You need not even listen, simply wait, just learn to become quiet, and still, and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked.” For Thomas Mann, “Solitude gives birth the original in us, to beauty unfamiliar and perilous — to poetry.” For Picasso, “Without great solitude, no serious work is possible.” – TED Talk

“If we don’t teach our children to be alone, they will only know how to be lonely.” – TED Talk

“It used to be that we imagined our mobile phones were there so that we could talk to each other. Now we want our mobile phones to talk to us.” – Reclaiming Conversation

“Erik Erikson writes that in their search for identity, adolescents need a place of stillness, a place to gather themselves.2 Psychiatrist Anthony Storr writes of solitude in much the same way. Storr says that in accounts of the creative process, “by far the greater number of new ideas occur during a state of reverie, intermediate between waking and sleeping…. It is a state of mind in which ideas and images are allowed to appear and take their course spontaneously . . . the creator need[s] to be able to be passive, to let things happen within the mind.”3 In the digital life, stillness and solitude are hard to come by.” – Alone Together

“One of the emotional affordances of digital communication is that one can always hide behind deliberated nonchalance.” – Alone Together

“Instead of thinking about addiction, it makes sense to confront this reality: We are faced with technologies to which we are extremely vulnerable and we don’t always respect that fact. The path forward is to learn more about our vulnerabilities. Then, we can design technology and the environments in which we use them with these insights in mind. For example, since we know that multitasking is seductive but not helpful to learning, it’s up to us to promote “unitasking.” – Reclaiming Conversation

“What do we forget when we talk to machines? We forget what is special about being human. We forget what it means to have authentic conversation. Machines are programmed to have conversations “as if” they understood what the conversation is about. So when we talk to them, we, too, are reduced and confined to the “as if.” – Reclaiming Conversation

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe