Credit: TED.com

This is the seventh in UnHerd’s week-long list of notable “Free Minds’. By their independence of intellect, clarity of vision and their courage in often defying powerful encouragements within universities, political parties and other public institutions to conform – they are essential agents of civilisation.

On a bleak Sunday evening last October I headed to Hammersmith Apollo in London to see a show. Queues of hundreds of people – mostly young – curled all the way in front of the building and around the block, destroying any chance of a pre-show drink in the bar. Yet that night the Apollo was not hosting a comedian or pop band. It was hosting an event with Sam Harris, the West Coast neuroscientist and author. He was joined in conversation by his fellow author and scientific atheist Richard Dawkins and the internet talk-show host Matt Dillahunty. But it was clear that it was Sam Harris that the crowd had come to see and his social media network that filled the 5,000 seater venue to capacity.

For the next 90 minutes Harris led the conversation on politics, science, ethics and God. When the time came for audience questions the queues for the audience microphones stretched to the back of the hall. The few questioners who did get a chance to ask something showed themselves to be part of a bunch of unusually cerebral people who were not only cool and diverse but clearly deeply engaged with their times. It was the sort of crowd any politician would dream of being able to attract, while very few mainstream media figures would even be able to fill the bar of such a venue (people might come for the celebrity but they would not be detained by the thoughts). Afterwards people mulled around, talking ideas, taking photos and finally getting those drinks in. In some ways it was like a rock concert, but a rock concert of ideas. For his followers, Harris is indeed a type of rock-star.

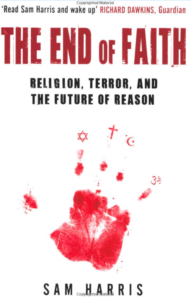

He first came to prominence in the post-9/11 years, firstly through his book The End of Faith: Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason. The book was an instant bestseller and was bracketed with a set of other ‘anti-God’ books that came out around the same time (not least Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion and Christopher Hitchens’s God is Not Great). He became identified along with them as one of the ‘new atheists’ and along with the philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett they all became known as the ‘four horsemen’ of the anti-theist movement of the 2000s.

He first came to prominence in the post-9/11 years, firstly through his book The End of Faith: Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason. The book was an instant bestseller and was bracketed with a set of other ‘anti-God’ books that came out around the same time (not least Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion and Christopher Hitchens’s God is Not Great). He became identified along with them as one of the ‘new atheists’ and along with the philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett they all became known as the ‘four horsemen’ of the anti-theist movement of the 2000s.

For those who were paying attention it was obvious even from The End of Faith that Harris’s contributions did not simply consist of arguing around an absence. The most controversial and brave parts of that book were not those aspects which reiterated in a newer and more sparkling form arguments against God which had existed before, but crucial arguments about what this meant for the moral universe the world now found itself in. What should the attitude of non-believers be in an era of mass-terror being committed in the name of faith? What accommodations could we (or should we) all come to agree upon? In his writings throughout the rest of that decade – not least in his crystalline Letter to a Christian Nation (2006) Harris remained focussed on this question. Not least because world events kept calling him back to the subject he had broken through in. Throughout events like the Mohammed cartoon crisis (2005 – ?) Harris proved to be one of the few people who had a certain enough moral framework, a developed enough understanding of what was being attempted and enough residual outrage to make a stand against such violent incursions of the most extreme forms of faith back into the public square.

It led him to be pigeon-holed, certainly. But by the turn of the decade it became clear that his strong anti-theism was not all there was to him (enough though that could have been). In The Moral Landscape: How Science can Determine Human Values (2010) and Waking Up: A guide to Spirituality without Religion (2014) he did what very few among the ‘new atheists’ had ever bothered to do. He attempted to build a positive case in the terrain which the new atheists had scorched. Unlike many in his own schools of thought he recognised that opposition was not enough, but that it was necessary to build and to address questions, rather than merely to savage them and shoot them down. What he engaged in was not what was elsewhere described as ‘Atheism 2.0’ but atheism as a starting point for all the important subjects which still followed.

Of course individual readers will have individual reactions to the level of success or persuasiveness of these ventures. But the sincerity of them, as well as the depth – and, perhaps most crucially – width of his learning is something which any honest critic as well as fan will note. His works draw not just on philosophy and history but on the very latest developments on science, in particular neuroscience.

Perhaps it is this cutting-edge that allows the ‘Waking Up’ podcast which Harris began in 2013 to reach tens of millions of listeners around the world. In these podcasts – a medium in which Harris was a relative pioneer – he mulls at length (sometimes for several hours) on the most serious themes.

Perhaps it is this cutting-edge that allows the ‘Waking Up’ podcast which Harris began in 2013 to reach tens of millions of listeners around the world. In these podcasts – a medium in which Harris was a relative pioneer – he mulls at length (sometimes for several hours) on the most serious themes.

He occasionally veers wholly into politics. But more commonly he delves into issues deep beneath the events of any day’s news. Recent podcasts have addressed ‘Consciousness and the self’ (a conversation with the professor of Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience, Anil K. Seth) and a conversation on ‘The science of meditation’.

These podcasts are an extraordinary phenomenon. With more than a million followers on Twitter, Harris is obviously able to point people to the irregularly posted discussions. But what is most extraordinary – as audiences like that in London in October evidenced – is their reach. Not just because they are listened to by millions of people at a time. But because in their reach they demonstrate the failure of a popular broadcast media intent on ‘gotcha’ moments and ‘X annihilates Y’ screen-grabs.

Harris shows an entirely different model of how to engage with your time and its challenges. Even with people who he has invited on with whom he disagrees he shows himself to be unfailingly, outstandingly courteous. Without any grandstanding he demonstrates continuously that thoughtful dialogue remains possible even between people who fundamentally disagree. When he crossed swords with the actor Ben Affleck on the Bill Maher show in the USA four years ago Affleck came across as a grand-standing ignoramus with a misplaced, Hollywood-induced, sense of his own significance. Even as he rolled his finger and ordered his fellow guest to hurry things along (as though Affleck were the director of all situations he graces with his presence) Harris dealt with him courteously, carefully and – as audience reaction showed – devastatingly.

It is the same in the conversations which he hosts. It is impossible to come away feeling that Harris has done anything other than give his guest their best shot. A recent appearance by Harris on Russell Brand’s podcast exemplified the idea. Brand showed off his wares in his familiar fashion (duck, weave, play the joker, turn into a pseudo-philosopher, then whoopsey-daisey there I go again, I’m a comic really etc, ad nauseum). All the time Harris takes even what Brand says as a serious proposition, countering him and correcting him, but always with a courtesy and an attention to facts so fastidious that it makes you wonder whether it mightn’t at some point even make some impact of Brand. In an age of intellectual dishonesty Harris’s way of communicating face-to-face as well as with his readers betrays a commitment to honesty as well as honest dialogue which is unusual. Of course it might yet prove essential.

Harris is still only 50. Many television bookers will not have read his works. Quite a number of opinion-page editors will only vaguely have registered him. But he is one of the free minds who is changing our world. And he’ll keep doing that whether the old media notice what he’s doing or not.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe