Laurence “Larry” Fink of Blackrock issued a warning to CEOs this year. Photo: Kris Tripplaar/SIPA USA/PA Images

The fifth in our ills of capitalism series looks at the deleterious effects of short-termism and flawed executive compensation schemes

First came the uncompromising manifesto, sharply critical of corporate excess and promising “an examination of the use of share buybacks, with a view to ensuring these cannot be used artificially to hit performance targets and inflate executive pay”.

Then came the clear warning to those running big companies that business as they knew was coming to end:

“Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate.[1. .’A Sense of Purpose‘, Jan 2018]”

Those who do not “will ultimately lose the license to operate from key stakeholders”.

No wonder some business leaders are quietly terrified by the revivalist movement among left-wing populists that includes Jeremy Corbyn, Bernie Sanders and Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

Except those words don’t come from the Left. The manifesto was that of Theresa May’s Conservative Party. And the warning to CEOs came from Larry Fink of Blackrock, the biggest investor in the world.

When criticism of corporate short-termism and self-interest comes from such sources, it seems fair to conclude that something is up.

Meanwhile, some things are down. Business investment, for example. Companies are spending less of their money on the technology, equipment and training that will, over time, make their operations and – crucially – their people more productive.

At the Social Market Foundation, we recently calculated that the cash reserves of UK non-financial corporations stood at £660 billion in 2016[2. .’Concentration, not competition: the state of UK consumer markets‘, SMF, 17 October, 2017].

Business investment that year was around £178 billion, or 28% of that cash pile. In 2000, businesses invested the equivalent of 58 % of their cash reserves.

Even allowing for fluctuations in the business and political cycle and changes in monetary policy over that period, companies are investing less. We’re nowhere near unravelling the puzzle of dismal post-crash productivity growth in developed economies, but it is extremely hard to imagine that corporate investment decisions have no part in it.

Dismal productivity, of course, means slow, low or even negative wage growth, which in turn means that when the Corbyns and Sanders and yes, Trumps of this world tell workers in traditional industries that they’re being screwed by a rigged system, they probably have a point.

In other words, the corporate titans who wring their hands about the rise of anti-capitalist populism might stop and ponder whether their own failure to plan – and invest – for the long-term might just have helped shake the pro-business, open-market political settlement they’d come to take for granted.

At the same time as companies have been investing less, they are handing more of their cash to shareholders. Dividend payments by UK companies were almost £95 billion in 2017, up 10% on the previous year, and the latest in a string of record highs.

On a narrow reading of corporate duties and responsibilities, dividends are reasonably defensible: it is, after all, the shareholders’ money.

Much harder to defend are the share buybacks mentioned in that Conservative manifesto – surely the first time any major party referred to a relatively obscure and technical bit of financial engineering.

Buybacks, where companies use their own cash to buy their own shares on the open market, are economically inexplicable. But if you’re an executive whose remuneration package is linked to earnings per share, they’re good business, because by reducing the number of shares in circulation you bump up EPS and make yourself rich(er).

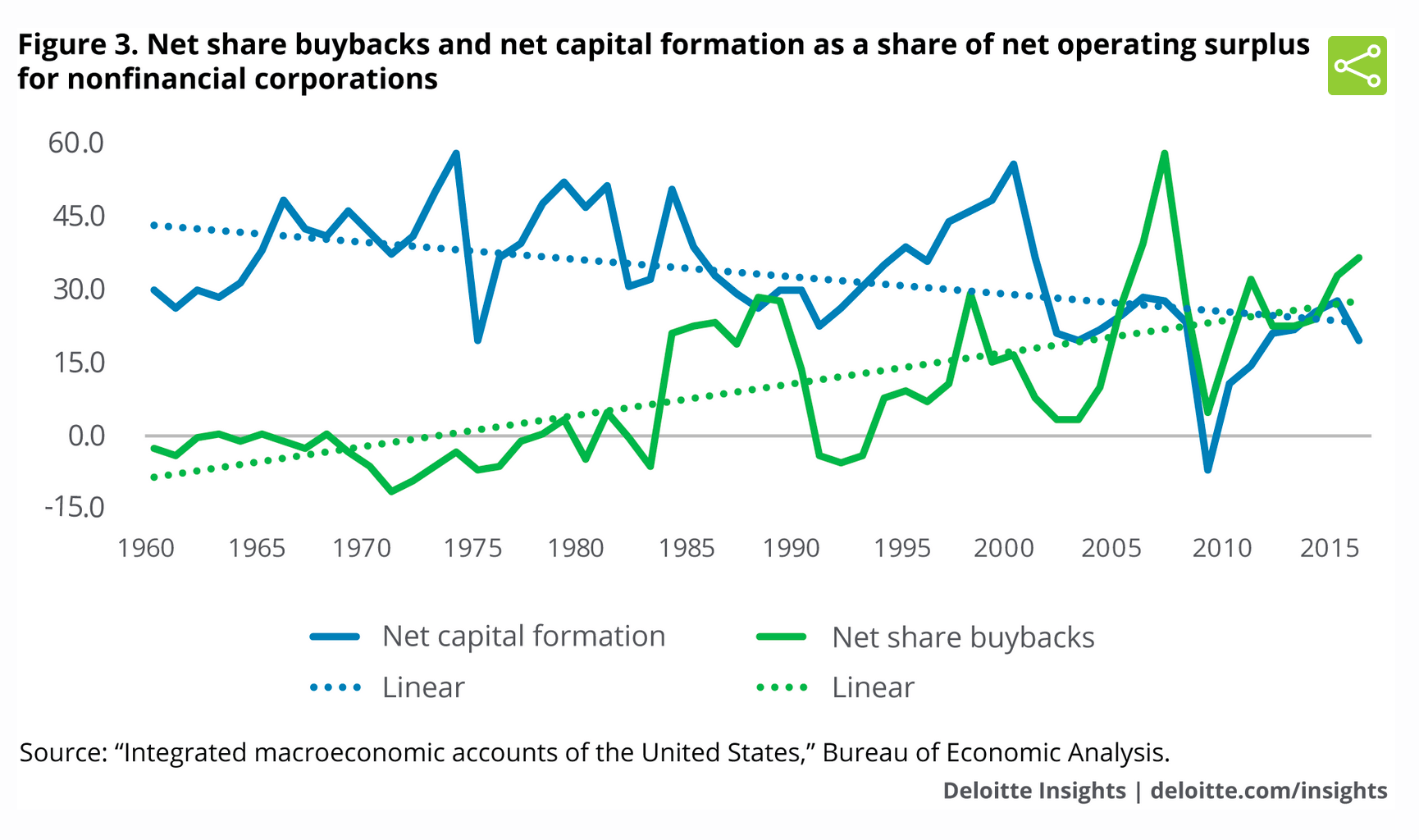

And they’re on the rise, as Charlotte Pickles explained here last month with devastating precision. Recent research from Deloitte nicely charts the trends in buybacks and investment.

What’s the answer? A lot of people talk about reporting rules, the fiduciary hoops that CEOs must jump through to keep markets and investors informed and content. Chasing good numbers for quarterly reports prevents executives taking a longer view, it is said.

After John Kay’s characteristically incisive report for the Coalition Government in 2012[3. ‘Kay review of UK equity markets‘, July 2012], the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) stopped mandatory quarterly reporting in 2014.

UK companies have duly started to move away from quarterly reporting: firms such as National Grid and Aviva led the way, and now 40 of the FTSE do not issue full reports every three months. In the FTSE-250, more than half have abandoned quarterly reporting. An end to short-termism? This battle is far from done. Work by Suresh Nallareddy and others at Oxford University questions whether a change in reporting periods alone can significantly alter corporate behaviour.

They found no clear evidence that moving away from quarterly reporting led to an increase in investment.

There is, then, still much to be done to persuade the people running big companies to think about more than EPS and annual profits.

Some of the answers will surely be found in other parts of the Kay Report, which also called for real change in executive pay deals, suggesting that much of the huge wealth bestowed on CEOs be locked away from them for years after their departure: that might create a real incentive to plan for the firm’s long term interests.

Breaking the curse of short-termism will require countless changes, not least in culture: “corporate social responsibility” has become a discredited PR wheeze that must sooner or later be replaced by an understanding that without a genuine sense of social duty, business will not just create its own gravediggers, it will ensure they get elected too.

But as a first step on that journey, start with CEO pay and tenure, which should be lower and longer.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe