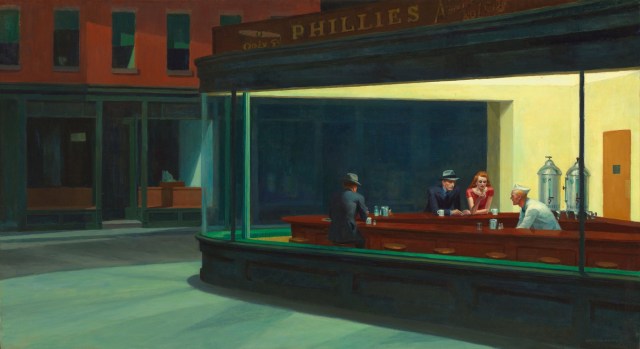

It’s like we are living in a permanent Edward Hopper painting, staring out of the window, alone, isolated (Credit Image: Edward Hopper via Wikimedia Commons)

Krishnan Guru-Murthy pushed himself back in his chair, clearly feeling more than a little frustrated at the very idea of a Minister for Loneliness. “Can you just give an example of how you might tackle one form of loneliness?” asked the Channel 4 interrogator, keen to find some solid ground in the discussion, something positive and concrete that the Government might actually do to tackle loneliness.

“Set up a metric” was the first answer given by the new Minister, Tracey Crouch. Rightly dissatisfied with the idea that simply measuring loneliness could count as an example of how to tackle it, Guru-Murthy asked again: “Just give me one example?” Something, anything, he was pleading. But concrete example there was none. “Loneliness is subjective,” said the Minister “so it’s very difficult.”

Perhaps I should start again. Set the scene in a completely different way and in a completely different century.

“I think therefore I am” is probably the most famous phrase in all of philosophy. It is also one of its greatest mistakes. For with this phrase, René Descartes – the so-called father of modern philosophy – led modernity into a cul-de-sac from which it is still struggling to escape. The back story is this: Descartes’ big intellectual project was to doubt everything that it was possible to doubt with the aim of finding something so solid and certain that he could build the rest of knowledge upon it.

Anything that could possibly be doubted was to be rejected. Only the completely indubitable would suffice. And here he discovered one thing – that although he could doubt pretty much everything, the one thing he could not doubt was that there was something doing the doubting; that is, he couldn’t doubt his own existence. And this was to be the basis for his project. I can know my own existence without a doubt, he insisted. This is the starting point. I think therefore I am.

The problem is the next step. For although I know that I exist, it’s not at all straightforward to know that anyone else exists with anything like the same certainty. How do I establish a connection, a bridge from the certainty of my existence over to the certainty of yours?

So off Western thought went seeking to answer this question: the so-called problem of other minds. And some people are still obsessed with it. They look at “other people” on the tube and wonder if they really exist. Are “other people” fake, they ask themselves, not real, a clever simulation, part of a dream? Is their subjectivity the same as mine? How could I ever know? It is as if we are trapped within ourselves, sealed in our own little perspective.

After years of doing philosophy, and teaching it, I no long care about this problem. It’s not that I have discovered a way to solve it. It’s rather that I don’t particularly care about the question. Personally, I think Descartes was extremely lonely. His mother died when he was a one year-old child. His father married again, and little René was brought up by his maternal grandmother and a nurse.

René never married himself. And I suspect that the solipsistic hole that Descartes dug himself was an articulation, in the form of philosophy, of the distance he felt from other people, of his basic alienation from society. And western philosophy was set up on this basis, to answer the problem of Descartes’ loneliness. The moral of this story I take to be this: beware of thinking about loneliness in such a way that it becomes unsolvable.

Loneliness is a problem in our society. It is a massive problem. Research has estimated that 9 million people in the UK would describe themselves as often or always lonely. Given the social stigma attached to loneliness – “no friends” being the classic schoolyard insult – I suspect that the figure may be considerably higher that 9 million, with many ashamed to admit their loneliness. 200,000 people said they haven’t had a conversation with anyone for over a month.

Modern life is a machine for the production of loneliness. Ever since the industrial revolution, when people were forced to leave their communities in search of factory jobs, loneliness has been at the very heart of the modern enterprise. Of course, people have always been lonely, in marriages, in communities, surrounded by friends and family.

So maybe industrialisation was not exactly the fall from some prelapsarian state of blissful togetherness, but nonetheless it was with industrialistion that the values of individual enterprise began to replace those of collective and communal living. It was here that the rational “I” began to replace the “we” as the subject of moral endeavour, and it was with the advent of the industrial revolution, and the move of labour from villages to cities, that an ethic of self reliance and individual freedom began to trump the morals of collective and mutual responsibility.

The Homo Economics was a child of Descartes’ rational and disengaged self. Both imagine the solitary individual making rational calculations of advantage. And yet, in theory at least, the division of labour that was at the heart of capitalism meant that co-operation was built into the way human beings were organising themselves economically. People had to rely on each other, and the specialisms that each other developed, in order to get things done. But it didn’t seem to bring us together.

In 1995 Robert Putman published his seminal essay “Bowling Alone”. It was a warning shot. American civil society, he claimed, was disintegrating. People no longer joined things – unions, political parties, churches etc. In this country, villages had increasingly become fancy dormitories as the pub and post office have closed down with people driving to their nearest supermarket, or getting deliveries online. Joining is down, volunteering is down, schools find it hard to find governors who will come out on a rainy night and sit on committees, increasingly people live within gated communities and have no idea what their neighbours’ names are.

It’s like we are living in a permanent Edward Hopper painting, staring out of the window, alone, isolated. Even the home itself has become atomised, with the collapse of family television and its replacement by social media, with the fake fellowship of cyberspace displacing real world experiences of actually meeting fellow human beings or even just sitting next to them on the same sofa.

But for all of this, and more, there is still always hope. Because most of us do not begin our lives isolated from others. The problem with Descartes cogito ergo sum is that it starts from the wrong place. In reality, first person plural comes well before first person singular. We are social and communal creatures long before we learn to be an individual. And if you dispute that, just stand outside a nursery gate of a morning and watch the teary eyes of small children as they are dropped off by their busy parents. The separation anxiety that all children display is all the evidence I need of the fact that human beings begin as connected to others, and have to learn to be independent.

Whatever challenges the human animal has in connecting up with others during this period of late modernity, whatever barriers we have placed between ourselves and other people, we are hardwired with a connection and a fundamental sense of togetherness. Family life will always be the main bulwark against loneliness.

Not all families look the same. As I was finishing this reflection I received an email from a fellow Vicar in Hackney, north London. He wanted to tell me about the Posh Club, a Tea and Cabaret Club for the over 60’s which has been established as collaboration between his church and the fabulous Duckie, a gay nightclub based out of the Vauxhall Tavern. He tells me that a Posh Club is now opening round my way too. And what a wonderful, life-affirming thing it is.

Here’s your example, Krishnan. Moreover, I challenge anyone to watch this video about the Posh Club and tell me that Descartes was right and that we are categorically separated from each other. No, we are fundamentally sociable creatures and we will always find new and unusual ways to reach out to each other, to create new families, whatever our differences and whatever barriers we have contrived to place between us.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe