Credit: Jonathan Brady/PA Archive/PA Images)

“I was absolutely astonished when I discovered there was a proposal to put into law the ability of shareholders to stop these excessive payments… I thought this was a power shareholders had always had”

That’s what Jacob Rees-Mogg said when I asked him about fat cat pay packages. “What is the point of owning the business,” he continued, “if you can’t even vote down the remuneration committee’s answers?” It’s a good question, but I think it misses the point.

Last year, the British Prime Minister referred to excessive executive pay as the “unacceptable face of capitalism”. Her manifesto, a few months earlier, had pledged to change that by legislating “to make executive pay packages subject to strict annual votes by shareholders”.

It’s easy to see why legislating to change behaviour – by giving the owners of capital the absolute right to vote against, for example, executive pay packages – looks attractive. Certainly, the current non-binding “say on pay” requirements – of which the UK was an early adopter, with the US following suit in 2011 – are a damp-squib.

Research by Stanford Graduate School of Business found that, overall, “granting shareholders the right to vote on executive compensation contracts has a fairly limited impact on pay”, which helps explain why pay levels haven’t been shifted in countries that have adopted it.[1. David Larcker and Brian Tayan, ‘Say on Pay research spotlight’, Stanford Graduate School of Business, 2016]

There is the odd case – like that of the construction company Crest Nicholson –where, despite shareholders voting against a pay package, the “advisory” nature of the vote has allowed the business to push ahead regardless. But, more commonly, where a majority of shareholders has voted no, action has been taken. The real problem is that shareholders are too often asleep at the wheel, and executives disinclined to moderate their behaviour.

So, while it’s disappointing that the Prime Minster has backtracked on her manifesto promise, the real question is: why do capitalists need legislation to make them do the right thing?

The writing is on the wall, capitalists need to read it

My colleague. Henry Olson. has pointed out that the experts who were blindsided by Brexit, Trump and the wider rise of populism across the West could have foreseen the upheaval. The data was there, they just weren’t reading it. Capitalists should take note.

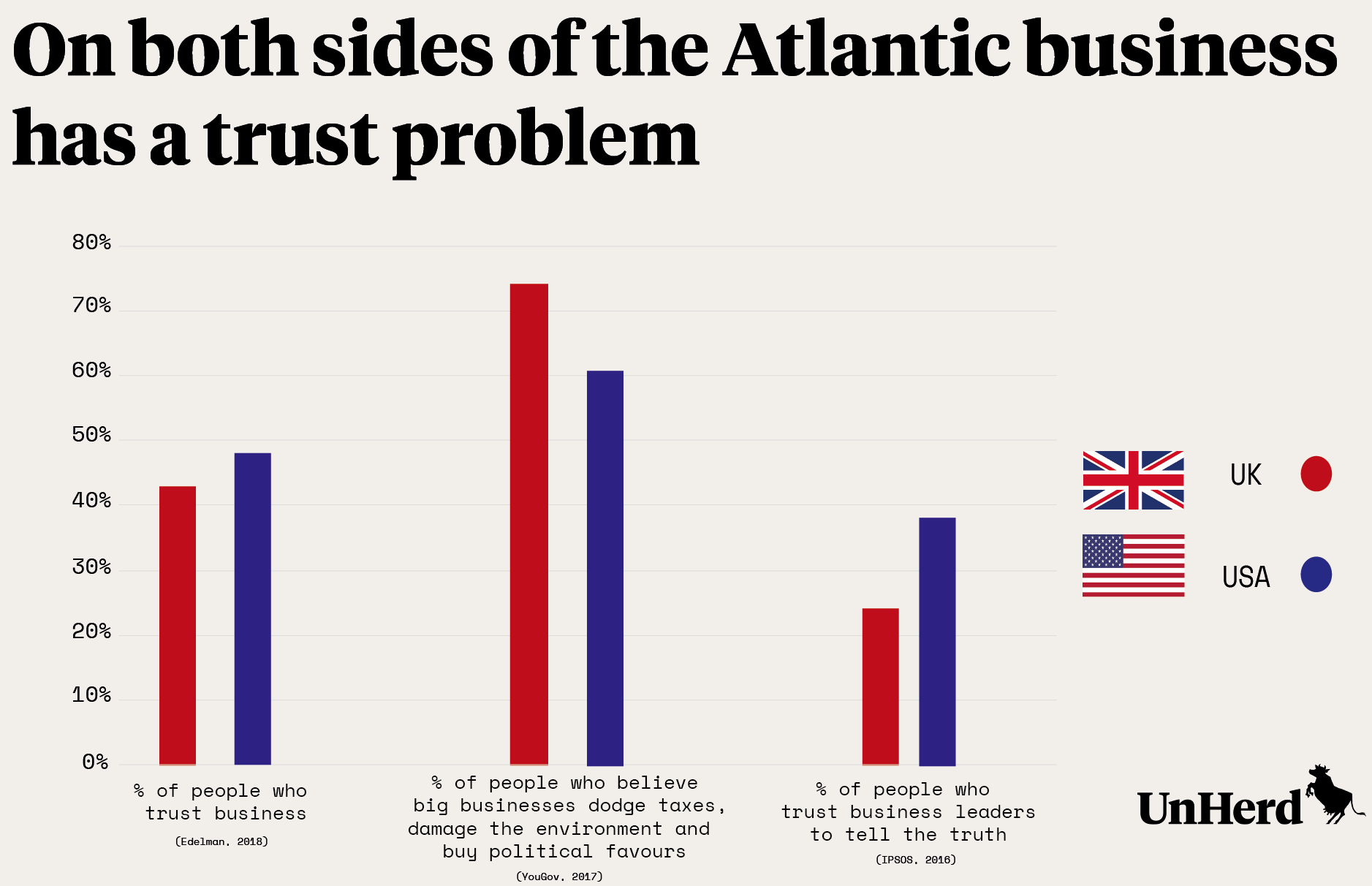

- Polling this month found less than half of Americans, 48%, trust business; in the UK it’s even lower at 43% – and on both sides of the Atlantic, that’s a decrease from 2017.[2. .‘Global Trust Index’, Edelman, 2018]

- Last year, YouGov polling for UnHerd found that three quarters of Britons and more than 60% of Americans believe big businesses have dodged taxes, damaged the environment or bought special favours from politicians.

- In 2016, just 24% of people in the UK and 38% of people in America trust business leaders to tell the truth.[3. .‘Trust in business leaders’, Ipsos Global Trends, 2016]

That’s pretty damning evidence that the people – those pesky individuals who sent political shockwaves reverberating through the West – are unhappy with corporate behaviour. In Britain, only those aged 65 or above are more likely to describe themselves as capitalist than socialist.[4. .‘British people keener on socialism than capitalism’, YouGov, 23 February 2016]

A hard-left Corbyn government, or socialist-styled Bernie Sanders administration, is no empty threat, it’s a very real possibility. Corbyn was a whisker away from winning last year’s UK general election, and many people, including Donald Trump’s own pollster, believe that Sanders could have won in 2016 had he been the Democratic candidate. The alternative to shareholders and executives putting their own house in order – or, to you and me, acting with integrity – is someone else doing it for them… and with a heavily anti-business bias.

Shareholders need to act

Rebuilding trust in business is, of course, going to take more than curtailing excessive executive pay – as important as that is – and at the start of 2018 we’re seeing encouraging signs that investors might just be getting it.

Larry Fink, the head of the world’s biggest fund manager BlackRock, used his annual New Year letter to CEOs to demand better behaviour.

“To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate. Without a sense of purpose, no company, either public or private, can achieve its full potential.”

BlackRock’s responsibility to its investors, Fink states, “goes beyond casting proxy votes at annual meetings”, it requires active engagement with companies. Warm words will not make the difference, but in beefing up their “investment stewardship’” team BlackRock is putting its money where its mouth is.

Another encouraging example is the shareholder resolutions filed at Facebook and Twitter this month by $200 billion New York State Common Retirement Fund and activist investor Arjuna Capital. The resolutions are aimed at forcing the tech giants to tackle abuse of their platforms. The shareholders want a detailed examination of the scope of abuse – including sexual harassment, hate speech and fake news – and an assessment of how the platforms are responding.

They also want the report to assess the financial and operational risk of “content management controversies”; which is a question other investors are likely to be interested in.

The collapse of UK facilities management and construction company, Carillion, shone the spotlight once again on fat cat corporates and their inadequate investor oversight. The Prime Minister is back on her soapbox, writing in The Guardian that: “for the first time, businesses will have to demonstrate that they have taken into account the long-term consequences of their decisions”. There’s no detail, and the Prime Minister’s track record is hardly encouraging, but it sounds ominous.

It’s time for the capitalists to get a grip and start rebuilding trust in business. That means active engagement with the companies they invest in, collective action and, ultimately, a willingness to act with their feet. The alternative, after all, is a whole lot worse.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe