Donald Trump takes the oath of office. Credit: Robert Hanashiro/USA TODAY/PA Images

Plenty of people who thought they knew the United States, most emphatically including Americans, are still reeling at the thought of Donald Trump in the White House. How could this lying, ignorant bully have become the 45th President? How could he have survived scandals that would have sunk most of his predecessors, the latest being a $130,000 payoff to an actress in pornographic films for what was, by her account, a not terribly exciting tryst shortly after his gorgeous third wife had given birth to their only son? How could Americans go along with someone who sang the praises of Vladimir Putin, called out journalists as “enemies of the people”, and refused to release his tax returns in the run up to an election?

Trump periodically reignites the shock with early morning tweets disparaging his opponents, reversing his positions, and displaying his ignorance of spelling, let alone grammar. Some of those who oppose him have succumbed to sheer fatigue. Others are at risk of having their fight-or-flight reaction triggered so many times that they feel the need to flee to distant areas free from wifi – although inevitably they return a week later, first celebrating the experience and then getting back to the business of hating with renewed and desperate energy.

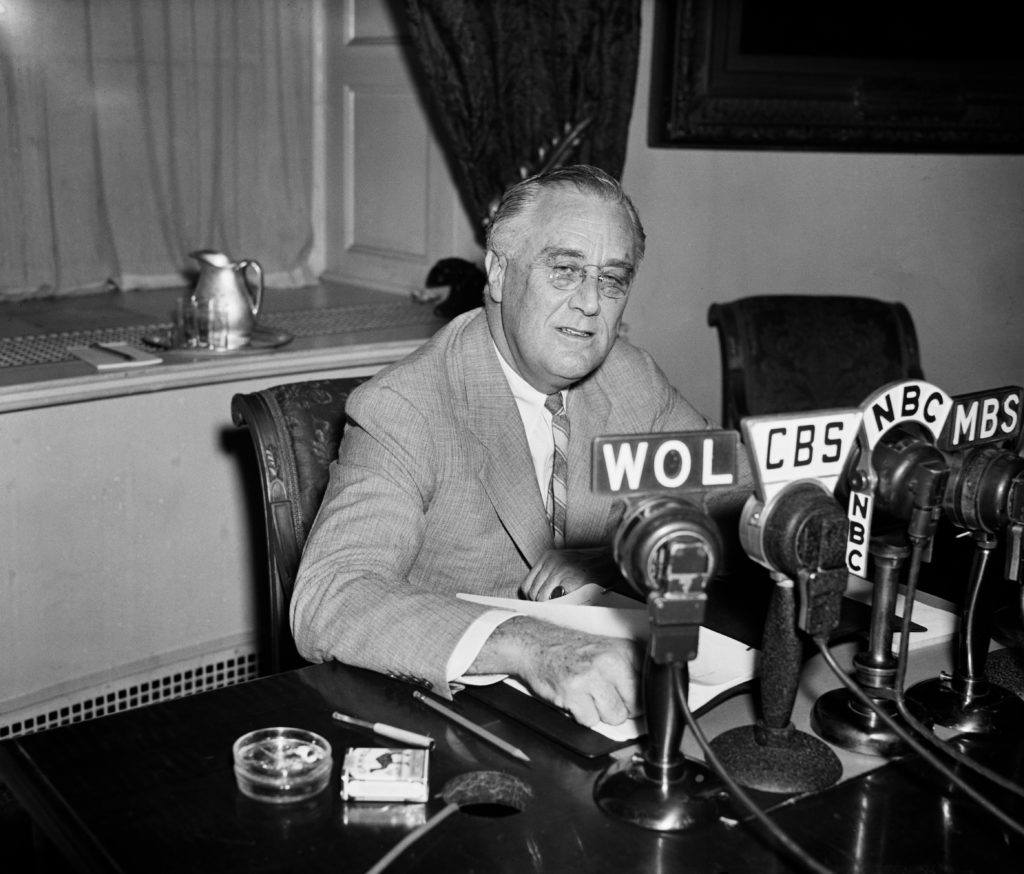

Trump is, in many ways, an outlier, but perhaps not quite as much as people sometimes think. Our alarm at his personality reflects the stature of the presidency since World War II, as well as his peculiarities. We are so horrified because our historical perspective is foreshortened. Americans and their friends overseas think of names such as Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Reagan when they think of the 20th-century presidency; even the lesser postwar presidents, such as both Bushes, Carter, Clinton and Obama, were substantial human beings, who quickly assumed the role assigned to them of Leader of the Free World.

That phrase now seems somewhat archaic, but it meant something: it was the United States that led the building of the postwar order for the democracies of Europe and Asia, and maintained it, with a reasonable degree of success, throughout the Cold War. It was the United States that played the largest role in shaping the denouement of that conflict, and then orchestrated, however clumsily, the response to threats from dictators and jihadists in the period afterwards.

In all those cases the presidency was central. It had become so partly because of the powers latent in the office, which were first tapped in a dramatic way by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War (to include the suspension of habeas corpus, expansion of the military without Congressional approval, and the partial emancipation of slaves); again by Woodrow Wilson during World War I and most dramatically by Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression and World War II.

The change took time, and it was marked by the little things. When Vice President Harry Truman found out that FDR had died he was playing cards with the Speaker of the House in a small room on the Capitol. He got up, and drove himself – in his own car! – to the White House. Unthinkable now, when, in the reflected glory of the President, the Vice President has an entourage of escorts, bodyguards, and aides who encapsulate him. The bubble Presidency emerged gradually. There once was a tradition, for example, that on July 4 any citizen could show up at the White House to shake the President’s hand. Theodore Roosevelt, characteristically, set the record for pumping the outstretched hands: over 5,000, by the end of which his hand had swollen painfully to twice its normal size. Again, unthinkable today.

To some extent, the Presidential bubble is a result of security precautions following the assassination of James Garfield, William McKinley and John F. Kennedy, and the serious attempts on the lives of Harry Truman and Ronald Reagan, among others. But what Arthur Schlesinger has called the Imperial Presidency is even more a reflection of the growth in the importance that Americans have assigned to that office in the last century. As a result, a President can no longer go for daily brisk walks around the city with reporters panting to keep up, as Truman did; whole city blocks are shut down by formidable Secret Service officers when the vast entourage of a President swings through. The presidency has become a kind of monarchical institution, but one without the charms of Buckingham Palace, the Changing of the Guard, and corgis.

The authors of the Constitution intended the presidency to have reserves of executive power for emergencies. There were indeed some who did actually see it as a kind of elective monarchy, deliberately removed from democratic pressure through the mechanism of the electoral college, which back then entailed indirect election through state legislatures. In the United States, the President is, somewhat unusually, both head of state and head of government, civilian head and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Lincoln knew what he was doing, and believed that he was acting within the Founders’ intent when he used these powers to the fullest to suppress the Great Rebellion, as his generation termed it.

But the Founders also built in powerful restraints on Presidential power through the ability of Congress to exercise oversight and control the funding of government; through the independence of the judiciary, and through the first ten amendments to the Constitution, which almost immediately were added to preserve both individual liberties of speech and collective rights of assembly and protest. And the entire system was federal: in the United States more than elsewhere, state and local government dominate and can (often do) resist federal rules and mandates.

The upshot of all this is that although Presidents may get most of the attention, they can rarely get their way. In 1937, shortly after a decisive re-election victory, at the peak of his popularity and power, Franklin Roosevelt tried to expand the Supreme Court so that he could stack it with judges favourable to the New Deal. A Democratic Congress shot it down. Sooner or later, as the great political scientist Richard Neustadt pointed out, Presidents learn that their power amounts to “the power to persuade” and except in wartime, not much more.

The real powers of a President are substantial, though less than they appear; the image they convey of supreme control is deceptive. And through a lucky accident – if accident it was – of history, Americans were blessed with a range of exceptional Presidents from the 1930s through the Cold War, with some reasonably able second-raters interspersed and thereafter. This is a lot better than the historical norm, a point that many have forgotten.

The United States had its Lincolns and Theodore Roosevelts before the great crisis of the 20th century. It also, however, had its James Buchanans and William Hardings. It has had slaveowners, boors, liars, and paranoids as Presidents. Even some of those with pretty good historical reputations had their dark side. Woodrow Wilson, for example, was a highly intelligent reformer. He was also a racist, and his rigidity caused him to blow up his own work at the Versailles peace conference by alienating such support as he might have garnered at home for it.

It has had Presidents, even some of the consequential ones, who were mentally ill. Nixon was a paranoid basket case by the end of his time in office, and Reagan was showing the early signs of the dementia that came on full force after leaving office. John F. Kennedy was, despite the tanned skin (less the result of sailing off Cape Cod than of Addison’s disease, one of numerous ailments from which he suffered) a sick man pumped up with drugs throughout his presidency. He was also a predatory philanderer.

What makes Trump distinctive? Almost all of his predecessors had had extensive political experience of one kind or another before coming into office. Even the generals such as Dwight D. Eisenhower or Ulysses S. Grant had been exposed to national politics through managing a coalition or navigating the complexities of internal politics in the midst of war. None, perhaps, has been quite so ignorant of the Constitution or dismissive of its restraints, although there are those who would argue, not without reason, that FDR did much more to stretch the limits of executive power than Trump has. Indeed, one can reasonably argue that Barack Obama, through his extensive reliance on executive orders rather than legislation by an opposition-controlled Congress, sowed the wind, and a fine crop of whirlwind now results.

The decline of Congress as an effective legislative body, as much as the rise of a presidency that can attract all the publicity as it wishes, accounts for the prominence of Trump. With all of their frustrating qualities, the House and Senate were once the loci of real power in Washington. Committee chairmen, protected by seniority and a culture of deference could kill a President’s proposals stone dead, and did, simply by sitting on them. That is what the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Henry Ashurst (a Democrat, it should be noted) did to FDR’s court packing scheme: “No haste, no hurry, no waste, no worry – that is the motto of this committee.” The best volume of Robert Caro’s magnificent biography of Lyndon Johnson, Master of the Senate, captures both how Congressional power worked, and the kind of individuals who wielded it.

Those days are past, for all kinds of reasons – the collapse of the old seniority system, the relative ease of travel which means that members and Senators scurry back home rather than learning to get along with one another, and the deepening partisanship of American culture. The repeated inability of Congress controlled by either party to pass normal budgets in a normal way is a grave indicator of just how bad things have become.

Trump is as much symptom as cause, the result of populist anger at government, a deep cultural divide that is also to some extent geographic, a shifting economy that endangers those with strong backs and willing hearts but not much else to offer the labour market, relatively higher than normal levels of immigration, and a general coarsening of norms of behaviour and civic knowledge and engagement. But he also deserves credit for certain abilities.

That Trump is a talented demagogue goes without saying, and, like all demagogues, he possesses the gift of tapping into his listeners sharpest fears and resentments. He has the gift of seeming authentic, truth-talking, rough around the edges in a way that people find a refreshing contrast to more contrived-seeming politicians. As Michael Flanders says in one of his skits with Donald Swann: “Always be sincere, whether you mean it or not.” He discovered early on the uses of Twitter, and has, more darkly, the talent of identifying and mocking an opponent’s key weakness with epithets like “low energy” “crooked” or “little”. His flouting of norms appeals in an age when norms seem, for a time, to have lost their grip.

Yet in one way he is a standout from other Presidents. He is simply not very good at his job. For all the bluster about being a great deal-maker, he does not know how to negotiate in good faith. Anyone who walks into the Oval Office knows that they are dealing with someone who will betray them at the drop of a hat.

Ronald Reagan could cut deals with Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill (last of the great old-time legislative politicians), and even two considerably more rascally and unappealing figures, Bill Clinton and Speaker Newt Gingrich, could come to terms with each other. Unlike Reagan, Trump had not thought hard about a political philosophy before office; unlike Obama or Clinton (both Bushes too), he could not master detail. Perhaps most extraordinarily, he does not seem to be able to elicit affection, warmth, or respect from talented subordinates – a wary servility is the most he can get.

He is, in short, remarkably mediocre as a politician and as a President. And for that, any patriotic American should be deeply grateful.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe