Prime Minister Theresa May and French President Emmanuel Macron at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst(Credit Image: Stefan Rousseau/PA Wire/PA Images)

When they stop shooting at each other, most professional soldiers – particularly British ones – get on remarkably well with former adversaries. Convinced of the superiority of their profession above all others, why wouldn’t they? “I’m a professional soldier” says the fugitive Swiss mercenary, Captain Bluntschli, in Shaw’s Arms and the Man; “I fight when I have to, and am very glad to get out of it when I haven’t to.”

So it was not surprising that after President Macron’s recent visit to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, hosted by Theresa May, Whitehall put out press releases extolling Anglo-French military cooperation, drawing on history to do so. They spoke of “a new Entente Cordiale” (which is worrying, given where the old one got us); and also of “the strong and enduring partnership between the UK and France and… [a] 100 years of military cooperation”.

It goes without saying that military cooperation with any Nato ally is a good thing. What is not a good thing, is to distort history in an attempt to promote cooperation, even if it seems to be distorting it only a little. For while not even the MoD’s pliant and ahistorical PR department would invite anyone to “reflect on the strong and enduring partnership between the UK and Germany and take a look back at 100 years of military cooperation”, the fact is that for 60 of those 100 years, the UK has had much closer military cooperation with the Bundeswehr than with the Forces armées françaises.

In his 1874 essay “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life”, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote:

“We need history for life and action, not for a comfortable turning away from life and action or merely for glossing over the egotistical life and the cowardly bad act. We wish to use history only insofar as it serves living. But there is a degree of doing history, and a valuing of it through which life atrophies and degenerates. To bring this phenomenon to light as a remarkable symptom of our time is every bit as necessary as it may be painful.”

Too true. So let us reflect accurately on those 100 years of Anglo-French military cooperation to bring to light that which might otherwise atrophy and degenerate, painful as it may be.

À double entente: a misunderstanding between friends?

First the Entente Cordiale. Signed in 1904, and therefore technically outside the century of reflection, it was nevertheless at the heart of the UK’s involvement in the First World War. It was not a treaty of mutual assistance (it merely resolved a number of longstanding colonial disputes and established a diplomatic understanding between Britain and France). But by the laws of unintended consequences and because military staffs make plans, it nevertheless managed, through faulty intelligence work and strategic thinking, to commit Britain’s comparatively tiny regular army to premature fighting in Belgium in 1914, which saw its virtual destruction by the middle of 1915.

Both Britain and France lost so many men in the war that their respective post-war military policies diverged enormously. After the allied occupation troops left the Rhineland in 1930, British policy on war in Europe became one of “limited liability”. It is an empty phrase, which allowed successive governments to pigeon-hole the growing German threat after Hitler came to power in 1933.

But it was also the result of, again, faulty strategic thinking. The French concluded that the foremost lesson of the First World War was the superior power of the defensive when backed by heavy artillery. The Germans concluded otherwise, and developed the concept of Blitzkrieg – lightning war – in which armoured forces backed by dive bombers (aerial artillery) bi-passed or pre-empted fixed defences. When, in 1939, Britain again found herself committed to war on the continent without having prepared for it, France once more called the strategic shots. The result was Dunkirk – and Vichy.

False National Memory Syndrome

The myth persists to this day that Churchill left the French in the lurch at Dunkirk. Whereas, in fact, the Royal Navy took off French and British troops from the beaches – and elsewhere subsequently – without differentiation. Churchill even proposed forming a political union to keep France in the war, fighting from North Africa. But although Paul Reynaud, the French prime minister, liked the idea, his cabinet was split. It was, said ministers, a last-minute British plan to steal the colonies. Marshal Philippe Pétain, the hero of Verdun (1916), said it would be “fusion with a corpse”. Reynaud resigned, Pétain asked for an Armistice, and formed what would become the Vichy Government – better to be a Nazi province than a British dominion.

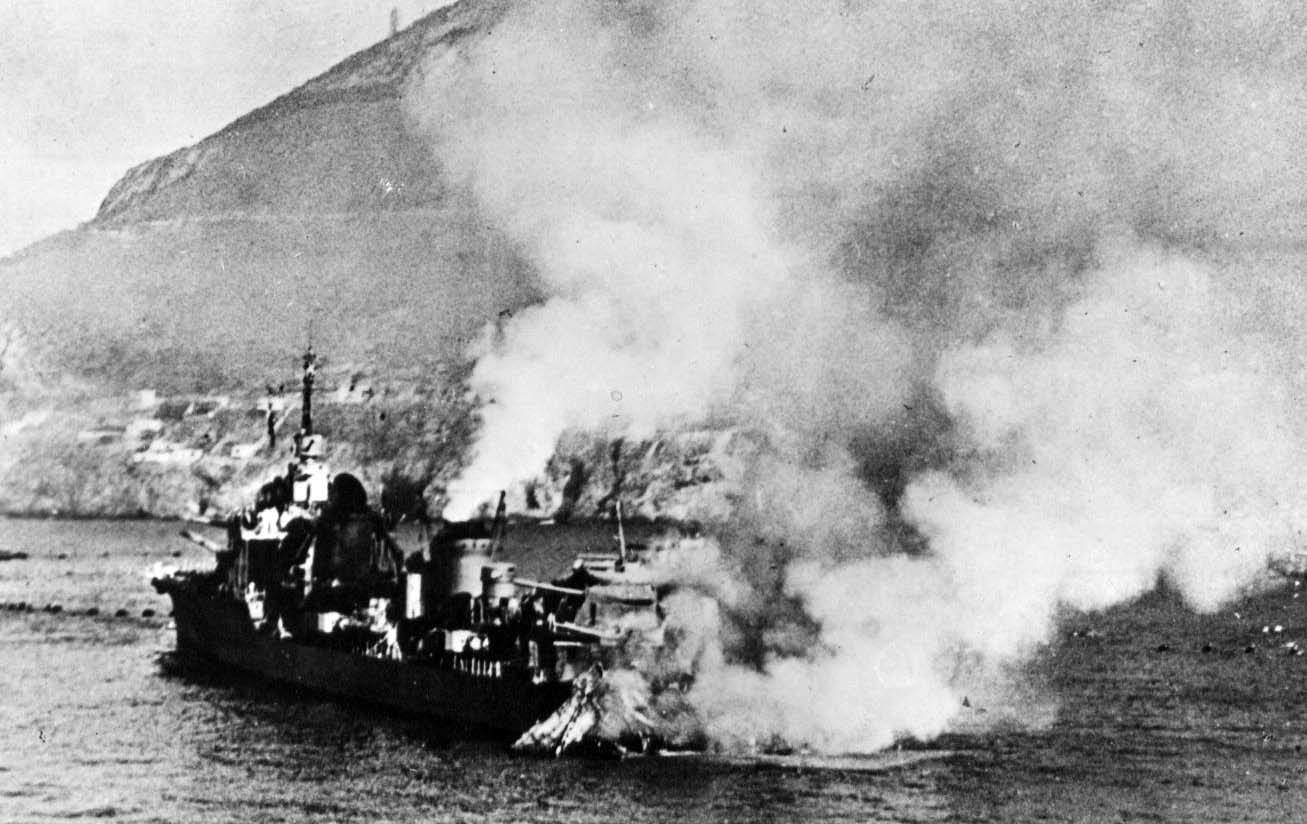

This placed Britain in the perilous position of having a Vichy French navy at large when German invasion now threatened. On 3 July 1940, Churchill sent a British fleet to confront a major part of the French Fleet at the port of Mers-el-Kébir outside Oran, (French) Algeria. His ultimatum was uncompromising: sail for Britain or the USA, or scuttle the ships. The French prevaricated, during which time London intercepted a message from the Vichy Government ordering more warships to Oran. Churchill told Admiral Somerville to “settle everything before dark or you will have reinforcements to deal with”.

Somerville did, and during the action 1,300 French sailors and marines were killed. In reprisal, the French bombed Gibraltar. They did so again in September after the Royal Navy shelled Vichy warships at Dakar in French West Africa (now Senegal) in support of troops from the sub-Saharan colonial territories who had rallied to General Charles de Gaulle’s London-based “Free France”. The following year, British and Imperial troops, along with Free French, fought Vichy and Axis forces in Syria and Lebanon, with considerable losses on both sides.

De Gaulle was a terrible thorn in Churchill’s side, but the one never actually said of the other: “The hardest cross I have to bear is the Cross of Lorraine” (the remark was made by General Spears, his envoy to France). Though de Gaulle was just as much an intriguer during the war as he was afterwards. Nevertheless, by the autumn of 1944 there were some 300,000 Free French troops fighting in France and Italy.

Politique de grandeur

When peace came in 1945, France again became one of the occupying powers in Germany. And then, when Stalin’s Russia became the threat instead, France became a key member of the Western Union Defence Organisation, precursor of Nato. However, Gaullist fears for French sovereignty led to France’s withdrawal from, first, in 1954, the WUDO’s successor project, the European Defence Community (it is probably better to draw a veil over the short-lived Anglo-French invasion of the Suez Canal zone in 1956) and then in 1966 from Nato’s integrated military command structure. De Gaulle asked all Nato troops to leave French soil and embarked on his “politics of grandeur”, a term just as apt today as “new Entente Cordiale”, but unlikely to be spoken of outside the Elysée Palace – for a while at least.

Only in 2009, was the decision fully reversed, by President Sarkozy, though after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the notional end of the Cold War, the integrated military command structure had in large part been dismantled.

This, then, is the history of the “strong and enduring partnership between the UK and France [and] 100 years of military cooperation”. It has undoubtedly been better than the military cooperation with any other European country (with the theoretical exception of Portugal), but it has not been consistently strong. And it was almost wholly absent in the great test of endurance – if ultimately only financial – that was the Cold War.

Actual military cooperation has been patchy to say the least, and even at its strongest it has not always been to Britain’s advantage.

All this matters not if Britain and France are now to cooperate fully. At the end of the day, Gladstone was probably right when in 1860 he urged an alliance with France “as the true basis of peace in Europe, for England and France never will unite in any European purpose which is radically unjust”. It is simply that to proceed with a faulty understanding of history is to risk repeating what Sir Edward Grey, the foreign secretary before and during the First World War, feared was “the Great Question” in the Entente Cordiale, and which he failed to answer: what are the limits of our obligations when there is no formal treaty and France has an agenda of her own?

As the Canadian Professor Margaret MacMillan says in her own prize-winning nod to Nietzsche, “The Uses and Abuses of History” (2009), history is fundamentally about the search for truth, and it is this pursuit that puts historians at odds with so many people who have a reason to be interested in it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe