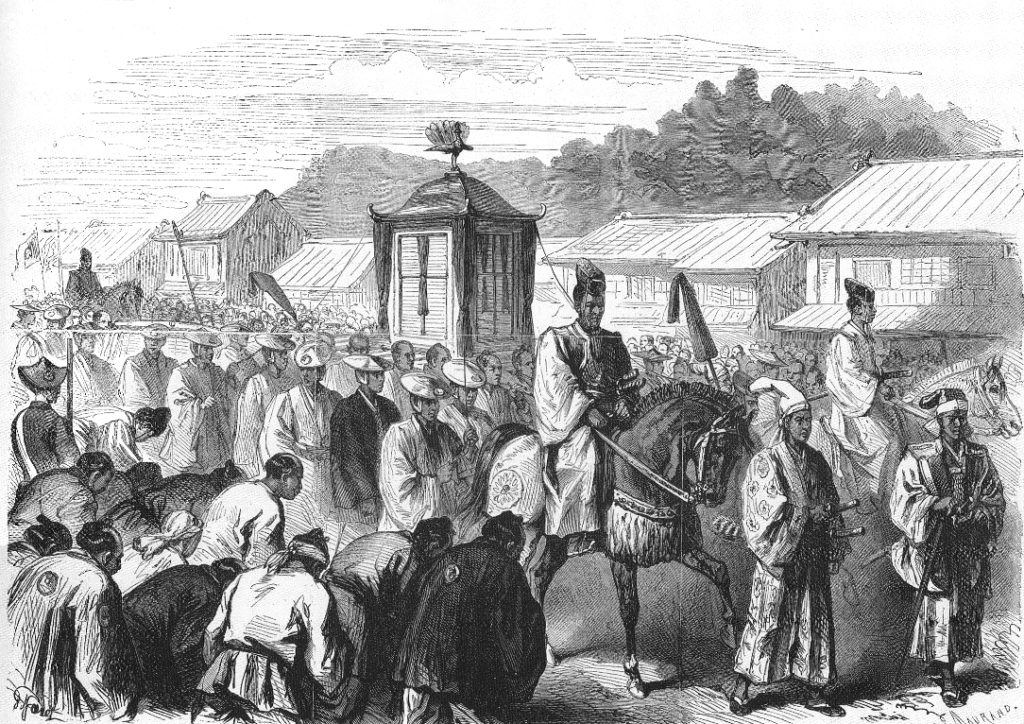

The Battle of Shiroyama (1877), one of the final acts of rebellion against the Meiji Restoration. Credit: Google Images

A visitor to Tokyo today might be surprised by the location of the British embassy. So close is it to the imperial palace, separated by just a moat, that the two could be one. (The visitor might also be surprised by the embassy’s Regency look, and within the compound its mock Tudor, but that’s another story.) The reason for its privileged position is that Britain backed the right side in the Boshin War (War of the Year of the Wooden Dragon), which began 150 years ago this month between forces of the ruling Tokugawa clan shogunate (military government) and those of the imperial court. Indeed, it is 150 years ago this week, 3 January 1868, that his supporters proclaimed the 15-year-old Emperor Mutsuhito ruler of Japan and the shogunate permanently dissolved.

Two years later Mutsuhito took the imperial name Meiji: “enlightened rule”. As we begin another year of the so-called Asia century, it is worth reflecting on the “Meiji Restoration”, for it underpins Japan’s self-image today.

“Enrich the country, strengthen the army”

For almost seven centuries Japan had been ruled by a shogun (military dictator[1. Shogun is the short form of Sei-i Taishōgun – “Supreme general for subduing the barbarians”, a title dating back to the 8th Century and the campaigns against the Ainu in Northern Japan.]), the emperor himself having only nominal authority. Motives for what was in fact a revolution were decidedly mixed, and not always what meet the eye. The Meiji Restoration has come to be identified with the rapid political, economic, and social change brought about by subsequent Westernisation, but the initial impetus for revolution was actually a fear that efforts by Western powers to “open” Japan, beginning in the 1850s with the acquiescence – encouragement even – of the shogunate after more than two centuries of near isolation, would subject the country to the same imperialist pressures observed in China.

The leaders of the restoration movement were mostly young samurai (warrior class) from hans (feudal domains) historically hostile to the shogun’s authority. Under the slogan “Enrich the country, strengthen the army” (Fukoku kyōhei), they sought a nation-state capable of standing equal to Western powers. (As in China, there were a number of “unequal treaties” to which they had specific objection.)

After the 3 January declaration, Yoshinobu, the ousted shogun, made war on the imperial faction, taking to the field with his larger and more modern forces, including several ironclad warships and French advisers. In the confusion of the fighting which followed, Royal Navy warships and marines found themselves in action against both sides as they tried to protect British commercial interests. However, the “Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary”, Sir Harry Smith Parkes, who had been in post since 1865 with twenty years’ experience in China before that, had earlier shown his distaste for the shogunate and encouraged instead the more progressive elements of the imperial party.

Although it had been the United States, with the American Civil War barely over, that had prised open Japan fifteen years earlier (Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy had sailed into Tokyo harbour with a squadron of warships to demand trade access) in 1868, Washington’s attention had not yet turned properly to the Pacific. German, Italian and Russian interests in Japan were not yet matched by muscle, and so Western involvement in the Boshin War was effectively limited to Britain and France.

France, with a large number of serving and former army and navy officers already acting as advisers to shogunate forces, appeared hostile to the restoration, while Britain, thanks in large part to Parkes (and the young diplomat Ernest Satow), appeared to support it. When Yoshinobu surrendered to imperial forces the following year, Britain was well placed to consolidate her advantage. The emperor had already decided to move his capital from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo), seat of the shoguns, where Parkes had been looking for a site for a new legation building. When the emperor abolished the old daimyo (feudal system), land in the imperial Chiyoda ward – Ichiban (Number One), indeed – became available, and he granted it to Parkes. The legation was completed in December 1874, though it was severely damaged in an earthquake after the First World War, and rebuilt in grander style. During the Second World War it was left in the hands of a caretaker, and when reoccupied in 1945, according to legend it had just a single broken window.

“A more humane Mikado never did in Japan exist”

In retrospect as well as at the time, the new Meiji government’s reforms were ambitious. Against much opposition – from the samurai, many of whom had given the emperor his greatest support in the civil war – the daimyo was broken down and the country restructured into prefectures, largely on the French model. Compulsory education was introduced, again based on the French system, then later the German. Universal conscription was also introduced, and a new army modelled on Prussian lines, while the navy was re-equipped and expanded with advice from the Royal Navy and contracts with British shipyards and armaments factories.

Although the economy continued to be largely agriculture-based, industrialisation was made the priority, especially transport and communications. The first railway was built in 1872, just four years after the first steam locomotive, an “Iron Duke” class, had been brought to Japan from Britain by Jardine, Matheson & Co, and by 1890 the country had more than 1,400 miles of railway. Telegraph lines linked all major cities by 1880, and a European-style (largely British) banking system and currency was progressively introduced after 1882. The textile industry grew fastest, and remained the largest Japanese industry until the Second World War. Political reforms culminated in 1889 with the proclamation of a European-style constitution and a bicameral parliament, the Diet.

Yet these reforms did not come without a price: there were several samurai insurrections, some of which the army were only able with difficulty to put down, and a severe economic crisis in the 1880s resulting from public-sector overspending. In part reaction to the pace of change, there was a revival of conservative and nationalistic feelings from the mid-1880s, including worship of the emperor (a revival that in part inspired Gilbert and Sullivan to write The Mikado[2. “Mikado” is the ancient, alternative name for the emperor, “Tenno” being the more usual. The part-heading “A more humane Mikado…” is the first line of the Mikado’s famous song in the G&S operetta, which Gilbert decided to cut after the dress rehearsal but reinstated after protests from the cast. Although set entirely in Japan, The Mikado is a satire on English society not Japanese.], and, later, Puccini to compose Madame Butterfly, a story based on Madame Chrysanthème, an autobiographical novel of 1887 by the French naval officer Pierre Loti).

The Rising Sun and the rule of Britannia

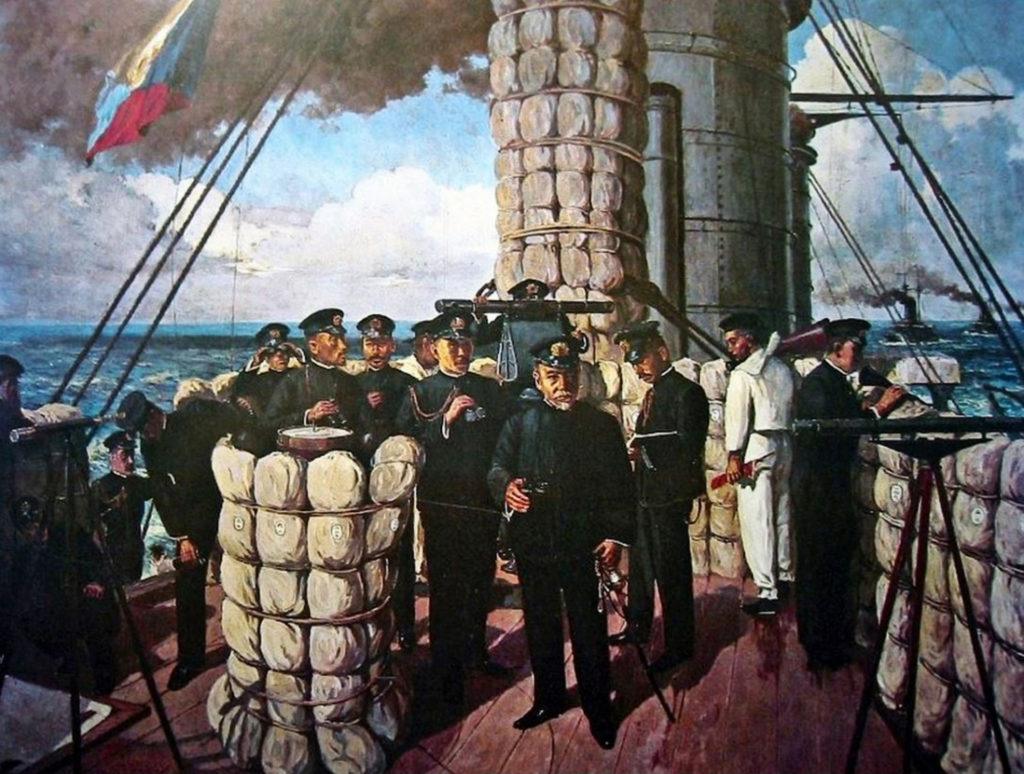

Growing competition with China in Korea led to the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, a victory from which Japan received Formosa (Taiwan), but was also forced by Russia, France and Germany to return other territories. This so-called “Triple Intervention” spurred even greater Japanese rearmament, however, and new conflicts of interests with Russia in Korea and Manchuria led to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, a resounding Japanese victory which further increased the country’s influence in Korea (which Japan annexed fully in 1910: https://unherd.com/2017/08/brutality-followed-brutality-followed-brutality-welcome-korean-history/ ).

Most importantly, the emergence of Japan as a serious military power led to the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902. The treaty was primarily directed against the shared threat posed by France and, more realistically, Russia in the Far East. It obliged either power to remain neutral if the other found itself at war with a third power. However, should either Britain or Japan be obliged to fight a war against two or more powers, the other signatory was obliged to provide military aid. The treaty thus played a part in keeping both France and Germany out of the Russo-Japanese War.

It was renewed and expanded in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911, and was the basis for Japan’s declaration of war on Germany on 23 August 1914. Indeed, the Imperial Japanese Navy, by releasing Royal Navy warships from the Indian and Pacific oceans, played a significant if indirect part in Britain’s gaining superiority in the Atlantic and North Sea.[3. From 1917 the Japanese navy played a direct part in the Mediterranean. By 1917, German and Austrian submarines operating were sinking Allied shipping at an alarming rate (a quarter of Allied shipping losses 1914-18 were in the Mediterranean). Japanese cruisers and destroyers provided a significant reinforcement for convoy escorts.]

Back to the darker ages

However, Emperor Meiji had died in 1912, and with him “enlightened rule”. In the post-war period a regressive militaristic gene took hold in Japan, bringing her into conflict first with Russia and then with Britain and America – with cataclysmic results: the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

Japan’s surrender led at once to complete disarming of the country, the United States taking responsibility for security, which was later enshrined in the new constitution. This was modified in 1954, however, allowing the raising of “self-defence forces” to enable more US troops to be withdrawn from Japan to take part in the Korean War.

Today, the Jieitai (Japan Self-Defence Forces) have more than 225,000 active-duty troops, a sophisticated navy (by some measures, the fifth largest in the world), and an air force with over 300 fighters. The prime minister, Shinzo Abe, has consistently raised defence spending and public support for the forces. Indeed, though less brash, and far from isolationist, his policy echoes the old samurai-Meiji slogan Fukoku kyōhei: “Enrich the country, strengthen the army.”

As Kim Jong-un defiantly pursues his nuclear weapons programme, and China increasingly flexes her muscles in the region, British and American military engagement with Japan is once again increasing. In this, the British embassy’s proximity to the Imperial Palace may well prove to be one of the more useful of the Foreign Office’s Victorian legacies.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe