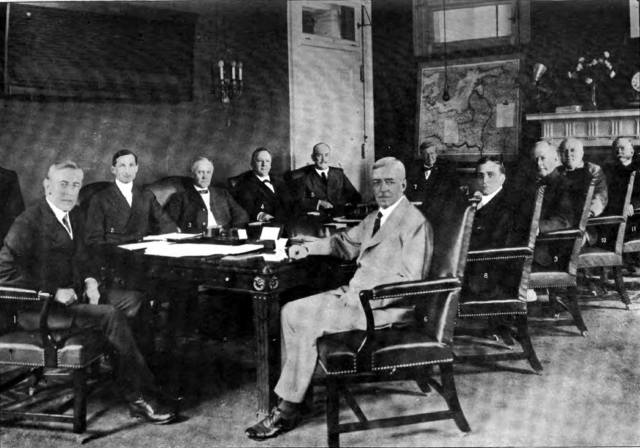

Woodrow Wilson, left, and his war cabinet. Credit: Encyclopedia Americana/Google Images

President Trump has never made a secret of his contempt for the United Nations. Before his inauguration he called it “just a club for people to get together, talk and have a good time”. The vote in the General Assembly on 20 December calling on the United States not to move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem (non-binding, 128 to 9, with 35 abstentions) will have done little to change that opinion.

The UN came formally into being on 24 October 1945, just a few months before Trump was born, though the name “United Nations” was coined by President Franklin D Roosevelt in January 1942, soon after the United States entered the Second World War. The UN’s roots go deeper, though – to President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points”, his terms for peace in the First World War. The US had entered the war in April 1917 on the side of the Allies – Great Britain, France, Italy, and Russia – although Wilson insisted on the (largely symbolic) term “cobelligerent” rather than “ally” to define the country’s status.

The US (briefly) emerges from isolationism

This week (8 January 2018) is the centenary of Wilson’s address to Congress in which he outlined his peace terms. While speaking directly to Congress, however, Wilson had two wider audiences, the warring powers – in particular the enemy – and the American people. He judged that America, instinctively and traditionally isolationist (although some, like the former President Theodore Roosevelt, had advocated joining the war almost from the outset) needed an overarching war aim that appealed to idealism. That aim reflected his own view: the country had entered the conflict as “a war for freedom and justice and self-government”.

This, Wilson believed, would also serve to break the will of the Central Powers by promising not simply an end to the slaughter, but a just peace. While he also believed that the allies had an urgent desire for an end to the slaughter, however, he underestimated their will to continue the fight. Casualties notwithstanding, their civilian populations (with the exception of Russia) were not suffering the same privations as those of the Central Powers – serious malnutrition, economic hardship and general war weariness.

He certainly wanted to exploit the fragility of the enemy’s “multinationality” too. The Central Powers principally comprised three multi-national empires: the German Hohenzollern (the most homogeneous, but not without internal tensions), the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburg (the most polyglot, culturally and religiously diverse), and the Ottoman Turkish, which even before the war resembled the Roman Empire in its over-extended, terminal stage. Wilson deliberately played to the growing ethnic unrest, principally in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, by promising national independence and self-determination for all peoples involved in the conflict, including those of the former Russian Empire, which since the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917 had withdrawn from the Allied war effort to negotiate a separate peace, and was in a state of incipient civil war.

The promise of national independence for the peoples of Central Europe was also instrumental in mobilising support among immigrant groups in America.

Wilson’s speech to Congress was short, just over 1,200 words, declaring at the outset that “the day of conquest and aggrandisement is gone by… It is this happy fact, now clear to the view of every public man whose thoughts do not still linger in an age that is dead and gone, which makes it possible for every nation whose purposes are consistent with justice and the peace of the world to avow nor or at any other time the objects it has in view.”

Compare and contrast

Wilson was nothing if not high-minded, as well as eloquent. A Democrat, the son of a Presbyterian minister, an elder of his church at Princeton while president of the university before becoming governor of New Jersey, it is hard to think of an occupant of the White House more antithetical to the present occupant than Woodrow Wilson. Yet the issues and vexations that Wilson faced and that Trump is facing have their similarities.

Eight of Wilson’s 14 points addressed specific territorial issues, the most important of which was that Alsace and Lorraine should be returned to France. The other six addressed the future conduct of international relations. There was to be an end to secret treaties, which he saw as one of the contributory causes of the war. There was to be “freedom of the seas”, which he defined as “absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants” – an objective which had the distinction of being opposed by both sides, notably Britain, France and Germany. Wilson also wanted reciprocal and free trade, limits on national armaments, and impartial adjudication of competing colonial claims.

Most significant, however, was Wilson’s fourteenth point, that “a general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike”. Wilson concluded his speech by asserting that it was for such arrangements and covenants that “we are willing to fight and to continue to fight until they are achieved; but only because we wish the right to prevail and desire a just and stable peace such as can be secured only by removing the chief provocations to war, which this programme does remove”.

In this notion of a “just and stable peace” there are echoes of Pope Benedict XV’s August 1917 “peace note”, which consisted of seven “concrete and practical proposals”, inviting “the governments of the belligerent peoples to agree upon the following points, which appear to be the bases of a just and lasting peace, leaving to the same governments to apply them at a specific level and to complete them”.

Benedict’s proposals received short shrift from both the Allies and the Central Powers, however. But although Wilson’s Fourteen Points likewise did little to hasten the end of the war (though they offered a measure of succour to nationalists in the Austro-Hungarian Empire who increasingly equated peace with their coming independence), they largely formed the agenda for the peace conference in Paris that followed.

America first?

Wilson, who with the other victorious leaders attended the conference in person – the first serving US president to visit Europe – soon discovered just how difficult it was to translate his high ideals into practice, not least because the Allies were intent, unsurprisingly, on establishing German war guilt and extracting reparations accordingly. They were no more interested in his wish – “[not] to injure her [Germany] or to block in any way her legitimate influence or power… We wish her only to accept a place of equality among the peoples of the world” – than they were in Pope Benedict’s idea of “peace without victory”.

Wilson did succeed, though, in winning support in Paris for his big idea, the “general association of nations”. The Senate had other ideas, however. The Republican majority leader, Henry Cabot Lodge, argued that the United States would have to give up too much power to the League of Nations, as it was to be called. In the vote 19 March 1920, the Senate emphatically blocked US membership. The League had held its first meeting, in London, in January, and in November moved to permanent headquarters in Geneva, in neutral Switzerland. Predictably, though, without US membership it quickly became, in Trump’s words of its successor, the UN, “just a club for people to get together, talk and have a good time”.

And the “Yanks” would be coming – “Over There” – again barely 20 years after ratifying the separate peace treaty with Germany (11 November 1921).

There is some irony in the situation of the two presidents vis a vis the “general association of nations”. For in aspiring to lead the free world in dealing with conflict, as Wilson had with his Fourteen Points, and as Trump does in his attempt to move on the Middle East peace process in the face of a general stasis, the one president saw collegiality as the answer, while the other sees collegiality as the problem. And while it was Congress that thwarted Wilson over the League and now largely applauds Trump over Jerusalem, there is no serious Congressional desire to withdraw from the United Nations.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe