Khalid A. Al-Falih, Saudi Arabia’s Minister of Energy, Industry and Mineral Resources and Russia’s Energy Minister Alexander Novak at Russian Energy Week last month. Credit: Artyom Korotayev/Tass/PA Images

This is part two of UnHerd’s deep dive into the oil market explaining the current state of the industry. If you haven’t already, check out our introduction to the series: Why the price of oil has been so hard to predict – and why that might change

Nowadays few people could name Saudi Arabia’s ‘oil’ minister, who as the Minister of Energy, Industry and Mineral Resources doesn’t even have ‘oil’ in his title. (He is Khalid al-Falih, by the way.)

Yet more than forty years ago many could easily identify the dapper Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani. He was the kingdom’s Minister for Oil from 1962 to 1986, and a major player in the OPEC association. Yamani’s celebrity was stratospheric, especially after he and other OPEC colleagues were held hostage in Vienna by the terrorist Carlos the Jackal in 1975.

Texas inspires OPEC

The Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries was established in 1960 by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

It was a cover version of the Texas Railroad Commission (TRC), which controlled US oil prices up until 1970 (when it relinquished this role and let US producers charge what they liked). Within a year there was no spare production capacity available in the US, which meant power over oil prices migrated to OPEC.

OPEC was never quite a cartel, for unlike the TRC it did not have the Texas Rangers as enforcers, as one American oilman quipped. Only Saudi Arabia had the power to unilaterally influence prices because of its huge ‘swing’ spare capacity, and even then it would need the other OPEC members follow its lead, something that has proved more tricky over time. The world’s largest oil producer is not, however, Saudi Arabia but Russia, which has always resisted OPEC membership since Soviet times, being unwilling to put the fate of its armed forces in the hands of an Arab committee.

Gold, dollars and oil prices

The 1973-74 oil price shock had a history. Oil producing nations had been angered by the US decision to come off the gold standard in 1971, depressing oil revenues which were earned in depreciated dollars. Some of the more militant Middle East and North Africa (MENA) regimes ‘de-colonised’ petroleum: for example Algeria’s new nationalised Sonatrach gobbled up French and US producers.

Oil might also be used as a geopolitical weapon, something the producers were slow to discover, partly because their industries were nascent and involved partnerships with western oil majors who in turn were facing competition from the newer breed of independents.

Algeria’s President Boumedienne joined Libya’s Colonel Qaddafi in linking oil supplies to western support for Israel. Symbolically when in May 1973 Israel celebrated a quarter century of independence, Algeria, Iraq, and Kuwait turned off their oil production for an hour, and Libya for the entire day. These countries also warned of an oil embargo should the West support Israel in any new war with Arab nations. The Saudis reluctantly fell in behind the radicals[2. Benjamin Stora, Algeria 1830-2000. A Short History, Ithaca 2001].

The Yom Kippur War and the 1973-74 embargo

On 5th October 1973 Egypt and Syria attacked Israel, pushing it onto the back foot for the first time. On 17th October OPEC declared an oil embargo against the US and the Netherlands in retaliation for their military supplies to Israel in the Yom Kippur War.

OAPEC (the Organisation of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries – a cartel within the OPEC cartel) raised the price of oil by 70%, and cut production in monthly 5% increments, so as to force Israel back to its 1967 borders. This entailed a net loss of 4 million barrels per day (bpd) until the embargo was lifted in March 1974. During that time, the price of oil quadrupled from $3 to $12 per barrel (in today’s money, $17 to $68).

The Arab producers (and the Shah’s Iran) categorised countries as ‘friendly’ or ‘unfriendly’ with no room for such would-be neutrals as Japan. This threatened to split the West, with the British and French the most craven towards the Arabs, while the Germans and Dutch took a harder line[2. For the details see Daniel Yergin, The Prize. The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power, London, 2008].

As stalwart supporters of Israel, the Dutch suffered badly, partly because Shell’s assets could be nationalised (as they were in Iraq) but also because of the huge importance of Rotterdam and Rijnmond which refined and distributed Middle Eastern oil across the rest of northern Europe[3. Duco Hellema, Cees Wiebes, Toby Witte, The Netherlands and the Oil Crisis: Business as Usual, Amsterdam, 1998].

The knee-jerk response

The impact of the oil embargo and price hike was dramatic, especially on societies in Western Europe and Japan which imagined they had left behind the austerities of a world war that was within living memory for most adults. US GNP declined by 6% between 1973 and 1975 and unemployment doubled to 9%. Long lines formed at US gasoline stations, 20% of which had run out of fuel by early 1974. The national speed limit was reduced to 55mph. Motorists with number plates ending in even or odd digits were only allowed to refuel on corresponding days of the month. Both the Daytona races and Christmas lights were banned. In 1975 manufacturers were required to raise vehicle mileage from 13.5 to 27 miles per gallon[4. These details, with striking illustrations, are from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History https://americanhistory.si.edu/american-enterprise-exhibition/consumer-era/energy-crisis].

The strategic response

However, the West adapted – as it has done ever since. High prices meant that costly and technically difficult exploration in the North Sea, Siberia, Colombia, Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico became financially viable. By 1983, the North Sea alone was producing more oil than Algeria, Libya and Nigeria combined. Soviet-supplied natural gas also relieved Europe’s energy demands without creating the strategic dependencies the Americans feared. Gas supplies were never once interrupted throughout the Cold War.

Presidents Nixon, Ford and Carter made energy independence a major national priority. In 1975 the US created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to store up to 700 million barrels of crude petroleum in salt dome caverns.

There was a brief revival of interest in unconventional ‘tight’ or ‘shale’ oil, though as in the First World War, this abated once conventional oil prices fell back. Successive US administrations encouraged the expansion of coal and nuclear in electricity generation, and the development of ethanol and synthetic fuels. Auto manufacturers ceased building heavy gas-guzzlers; Japanese compacts and European hatchbacks replaced saloons and sedans. There were also moves to improve home insulation, and to use energy more efficiently in factories. The US government imposed price controls on domestic oil so that US producers effectively cushioned US consumers with subsidies.

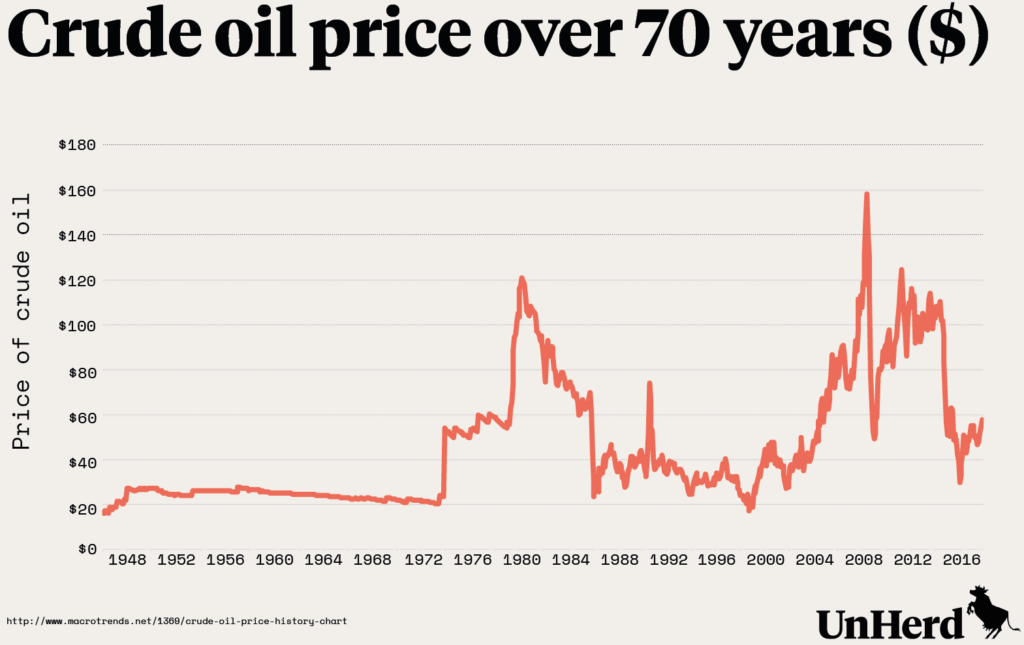

Oil prices soared again to a high of $35 per barrel in 1980 because of the Iranian Revolution in 1979-80, followed by the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war which subtracted 6.5 million bpd of supply. But then it fell to $10 by 1986 as alternative supplies came on stream.

From peak oil to peak demand via myriad zigzags

Almost anything influences the price of oil, from hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico to strikes in Venezuela, the 2011 Arab Spring, rumours of war with Iran, or the opaque activities of commodities futures traders and hedge funds[5. On NYMEX and ICE see Daniel Yergin, The Quest. Energy, Security and the Remaking of the Modern World, New York, 2012]. Even a significant birthday can do this, as was the case with speculation that the former Saudi oil minister Ali bin Ibrahim al-Naimi would retire on his 80th birthday, leading to a reduction in production by his successor. In fact, Saudis don’t much celebrate birthdays, and the minister retired later.

Despite a brief hiatus in 1990, coincident with the First Gulf War, crude oil prices steadily declined in the early 1990s. Adjusted for inflation, the 1994 price was the lowest since 1973.

From the mid-1990s oil prices rose again, partly because market-driven turmoil in Russia led to a five million bpd loss of production between 1990-96. This took place at the same time as a rise in demand from the Asia-Pacific region where Japan and South Korea produce virtually no oil, and China is, since 1993, a net importer.

Prices next fell at the end of the 1990s because of a combination of the Asian financial crisis and OPEC over-production. But then came a long rally in demand in the 2000s, which peaked at a record $147 bpd for Brent Crude in 2008. This collapsed with the financial crisis but quickly recovered, despite the Great Recession in the West after 2008, thanks to demand from a rapidly growing China. In 2009 Chinese new car sales exceeded those in the US for the first time[6. Yergin, The Quest p. 219]. Between 2011-14, oil prices hovered around the $100 mark, but then in 2015 came the latest twist when prices suddenly halved. The price seems stalled at about $50 per barrel[7. Obviously there is not a unitary oil price since there is Brent Crude or West Texas Intermediate to consider separately because of their viscosity, volatility and toxicity, among other factors.].

A glut?

Today’s fear is of a glut, with many oil majors planning for the new era of peak demand rather than peak oil (supply), and they have already cut back investment in their more venturesome explorations to the tune of $400+ billion so far. In advanced economies, growth is decoupling from energy consumption, with even the EU acting robustly to diversify gas supply away from Russia[8. Lynn Cook, Elena Cherney ‘Get Ready for Peak Oil Demand’ Wall Street Journal 22 May 2017. Chevron and ExxonMobil don’t forecast any peak. BP locate it in the 2040s, Royal Dutch Shell in 2025-30, Statoil in 2030, Total in 2040 and the International Energy Agency say ‘after 2040’. The views of Rosneft, CNOOC and Sinopec were not solicited. Future EU gas supply is likely to come from the Caspian region (Iran) and the East Mediterranean (Egypt, Israel, Cyprus) though there are geopolitical problems with both.].

The glut is attributable to the US shale oil and gas revolution – made available through advances in fracking technology – which might be replicated elsewhere. Meanwhile we are all becoming more conscious of how we use energy. In 2015 the Saudis deliberately increased production to almost maximum capacity, so as to bankrupt US shale producers, to hurt the Shia Iranians (who were returning to market after the 2015 nuclear deal ended sanctions) and to grab a larger market share in Asia. The result was that the US shale industry simply pedalled harder, with technological leaps and bounds generating more efficiency gains. Although Libya is in anarchy, and much oil is stolen in the Nigerian Delta, both Iran and Iraq are producing a lot more oil too.

Geopolitical consequences

Assessing the wider geopolitical impacts of sudden oil price movements is not straightforward. Let’s look at two. One resulting from historic price highs, the other from contemporary price lows.

Since the 1973-74 oil price shock, the US has been involved to a far deeper extent in the turbulent Middle East than before. The key dilemma was how to square economic self-interest with stalwart support for Israel. Every US Secretary of State has followed Henry Kissinger in touring the region, to diminishing effect, even after the contemporary US shale oil revolution might have resulted in wholesale disengagement. Clearly it is not ‘all about oil’, though as President Trump’s recent visit to Riyadh illustrates, oil revenues obviously relate to both US arms sales and the lure of Gulf investment in Western economies[9. Henry Kissinger, Years of Upheaval, London, 2011. The British monarchy (and many retired army generals turned salesmen) has multiple ties with the deferential autocracies of the Gulf, though it is arms sales rather than oil which influence policy nowadays, in line with the supermarket maxim ‘TWOFOR’: ‘buy our arms and get our foreign policy free’].

We have yet to witness the full impact of chronically low oil prices on the stability of the Middle East – though given the example of Venezuela, one suspects that trouble is coming. It is said that some MENA regimes need an oil price of $100 to break even[10. Saudi Arabia needs an $83 break-even price, Iran about $51. Iran has a functioning individual and corporate taxation system of course (devised by Deloitte Canada)], though none has yet gone bust.

The 2011 Arab Spring was certainly destabilising, but it was not caused by oil; Tunisia, Egypt and Bahrain hardly have any. Rather the protests were triggered by corruption and disrespect for human dignity as symbolised by the slogan ‘Enough!’

Oil exit

Oil revenue has traditionally shielded Gulf Arab rentier petro-monarchies from being democratically accountable, since production costs are low ($10-20 pb in Saudi Arabia) and their peoples pay no taxes, while benefiting from subsidies that meant that gasoline was cheaper than bottled mineral water. With revenues on the slide, budget cuts, borrowing and repatriation of overseas investments are not enough to compensate. Even the Saudis are down to their last $500 billion of sovereign reserves. Hence the vaulting ‘Vision 2030’ of the tyro Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, a glorified McKinsey report setting out a new non-oil-dependent utopia for his people[11. For a longer, skeptical discussion, of Vision 2030 see Michael Burleigh, The Best of Times, The Worst of Times: A History of Now, London, 2017 chapter 2. See also Simon Kerr, ‘Saudi Arabia redrafts crown prince’s transformation plan’, Financial Times, 7 September 2017].

Most of the MENA states are pondering how to diversify their economies away from hydrocarbons and into manufacturing, armaments, finance, pharmaceuticals, renewables, technology and tourism, while downsizing their bloated public sectors and abruptly phasing out the foreign remittance men and women who do most of the work. This in turn will hurt places like Egypt, Bangladesh, Pakistan and the Philippines.

This transition could be politically explosive, not least for Mohammed bin Salman, who is antagonising conservative Saudis (not to mention other princes who lost out in recent succession struggles in which he elbowed his own uncle aside). It will get worse if westerners (and the Chinese) opt for electric vehicles in large numbers, while asking themselves why they should care about sybaritic Emirati, Qatari and Saudi autocrats driving Maseratis in Mayfair.

Stones and oil

In his dotage, Sheikh Yamani went on to be a prophet, predicting in 2000 that the ‘oil age’ would finish, famously opining:[12. Mary Fagan, ‘Sheikh Yamani predicts price crash as age of oil ends’, The Daily Telegraph, 25 June 2000.]

“The Stone Age came to an end not because we had a lack of stones, and the oil age will come to an end not because we have a lack of oil.”

If today’s adaptation by the West is permanent, and demand destruction continues, this time it will be the Middle Eastern extractors that will need to adapt.