Credit: d3sign

This July, the EU’s landmark €2.4 billion antitrust judgment against Google punctuated more than a decade of Euroskepticism towards big technology firms. US public opinion about tech giants may still be fairly positive , but the European decision has fed a mounting wave of reflection in America about our home-grown titans. As that debate unfolds, it will require an expansion of the terms of antitrust discussion, because the tech conglomerates’ power is built on something we haven’t traditionally thought of as a pillar of monopoly power: information.

Is the tide turning against the tech monopolies?

The US debate over tech monopolies has been shocked to life by a succession of illustrative cases. First and foremost, the evidence that a Russian-backed social media campaign skewed the 2016 election has driven home a sense that Facebook has transformed from a toy for teenagers into a behemoth in need of serious oversight. Congressional hearings on the issue began Tuesday. Meanwhile, Amazon’s $13.7 billion takeover of Whole Foods in July triggered terror among grocers, and Congressman David Cicilline requested hearings about the deal on antitrust grounds.

A lower-profile but more insidious episode came in late August, when the Open Markets anti-monopoly research group was pushed out of the think tank New America. While the details are disputed, Open Markets head Barry Lynn alleges that his group’s ouster came under pressure from Google, a major funder of New America, after Open Markets praised the EU judgment. Lynn, in the statement that he says got him fired, said the decision protected “the free flow of information and commerce upon which all democracies depend” against Google’s massive reach.

A tale of David and Google-iath

The responses have been remarkably direct, considering that tech innovators have been held up for decades as icons of American exceptionalism. The American Conservative in September called Facebook, Amazon, and Google “the new robber barons” and crony capitalists. New York Times tech columnist Farhad Manjoo in October officially launched his own crusade against what he calls the “Frightful Five.”

Manjoo gets to five by generously granting Microsoft and Apple legacy status. Those companies are indisputably giants, and they fit an easily-grasped rubric. In the 2001 U.S. antitrust case against Microsoft, courts found that the company had illegally used its control of a piece of infrastructure – Windows – to protect its other software from competition. Apple has similarly worked to lock down everything from entertainment to payments in its iOS ecosystem. It’s not a giant conceptual leap to connect such tactics to the way 19th century railroads extorted farmers: successful operating systems, like consolidated rail networks, are an opportunity for rent-taking.

When users aren’t customers

But Google, Facebook, and Amazon are different. Their defenders often argue that “competition is just a click away,” since you can easily use a different social network (they do exist), a different search engine, or a different web store. And because Google and Facebook are free for users, it’s difficult to square them with our image of the ur-monopolist who corners a market and then inflates prices.

That’s because Facebook, Google, and even Amazon’s users aren’t actually their customers. Despite what can look like wildly diverse product portfolios, Facebook and Google make almost all of their revenue from web and mobile advertising. Though Amazon’s profitability is surprisingly dependent on its cloud computing services, the bulk of its revenue is driven by its ability to show users products they want to buy – the fact that they actually fulfill the resulting orders is secondary.

This sort of targeting depends on one asset: user data. It’s user data that lets Amazon show you the same ad, for something you didn’t even know you wanted, on three different websites. It lets Google individually tailor both search results and accompanying ads, and Facebook keep you coming back by insulating you from facts that conflict with your beliefs. In essence, user data are these companies’ rails, delivering buyers to sellers with unbeatable efficiency.

Robber baron technique, then and now

The tech giants built those rails in much the same way previous robber barons did – through a combination raw creative vision, first-mover advantage, and relentless expansionism. Google was undoubtedly superior to almost any other search engine when it first appeared in the late 1990s. Similarly, Facebook won the social network wars because it was simply better than MySpace or Friendster.

But just being dominant doesn’t make a company a monopoly deserving of regulation – the new giants have worked furiously to build anti-competitive moats after gaining their early leads. That has included some old-school tactics, with Google in particular inheriting AT&T’s lust for regulatory capture to supplement its funding of friendly policy research.

Google’s vast appetite for data

But the new giants also have a novel path to total dominance: acquiring huge caches of data wherever they may be found. For Google, that began with the reasonable-enough purchases of ad networks like AdMob and Doubleclick, but has since metastasized wildly. It has gathered patient health data from Britain’s National Health Service, got inside your house with smart-home pioneer Nest, and regularly harvests road traffic data through local governments.

Not all of that data has been brought to bear on ad targeting, but it takes a great deal of credulity to believe Google won’t eventually do just that. In fact, one compelling argument that Google and Facebook have anticompetitive market positions is their apparent inability to make money on much other than advertising. They are, at root, the same sort of media conglomerates that U.S. regulators once regarded as enemies of democratic discourse – but on a global scale.

Collateral damage mounts

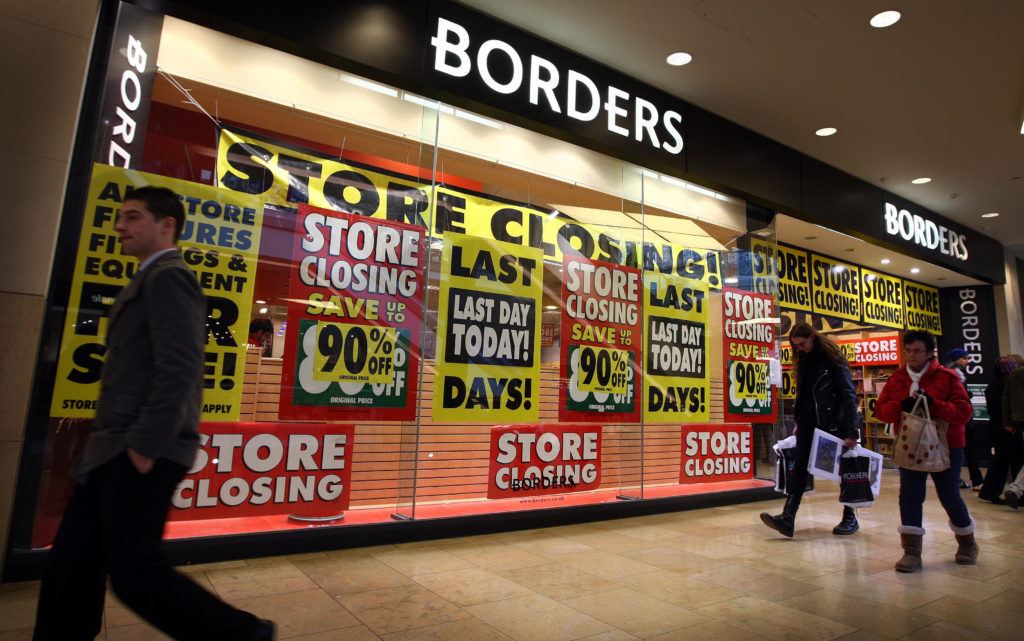

The casualties of this concentrated ownership of consumer data are plain to see. Newspapers and magazines have been gutted because their audiences aren’t large or diverse enough to be anything but feedstock for Facebook and Google’s gargantuan ad mills. Brick and mortar retailers are cratering left and right, partly because we’ve (re)discovered the convenience of delivery, but mostly because even sellers with robust online stores can’t profile customers as precisely as Amazon.

The biggest firms have also crushed their online advertising competitors. Google has brazenly appropriated the content of smaller websites to place snippets in search results, gutting the smaller sites’ traffic. Twitter, despite its cultural omnipresence, can’t figure out how to effectively make money from ads without Facebook’s scope. Neither could Yahoo!, a diversified entity that might have actually had a shot, and the once-hyped social network Snapchat is currently playing out the same narrative of futility. In perhaps the ultimate indicator, BitTorrent directory The Pirate Bay is apparently struggling to turn a profit selling ads even against stolen content, and has experimented with hijacking users’ computers to mine cryptocurrency.

Winner take all?

There are a few possible ways of muting these anticompetitive effects. Through the mid-20th century, it was still common in America to simply break up firms that became too dominant. Something like the AT&T settlement, which assigned separate geographic territories to newly created “babies,” could work for Facebook or Google. Amazon could be constrained to stick to online retail and spin off side-projects. More modestly, regulating particular behavior could make Facebook and Google more like public utilities – recent proposals to regulate political advertising on social sites would be a step down that road.

But another, more radical solution is worth considering. Mandatory data-sharing regulations would force web companies to compete on the basis of what they create, not just what they own, by taking away the insurmountable head start enjoyed by Facebook, Google, and Amazon. Right now, the sale of access to user data in the form of advertising seems like a textbook example of rent-seeking. It’s debatable, in fact, whether there should be a right to third-party ownership of such personal data in the first place – just ask the EU. Or Equifax.

But of course, no antitrust action at all seems plausible under the current US regime, despite President Trump’s rhetorical claims to care for the little guy. Peter Thiel, an entrepreneur and early Facebook investor who is one of Trump’s only remaining supporters in the tech sector, explicitly calls Google a monopoly in his 2014 book Zero to One. But he defines monopoly as “a kind of company that’s so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute,” and explains that Google’s monopoly is socially beneficial because it lets it treat its employees well.

Google has about 70,000 employees, less than a quarter as many as even today’s much-weakened General Electric. Thiel’s belief that serving them is a worthy tradeoff for a radical concentration of economic power is just one more index of how little bothered he or the other Trumpists are by the winner-take-all reality that we live in now.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe