(Photo by Lintao Zhang/Getty Images)

Just under a month ago, I was denied entry to Hong Kong, on the orders of the Chinese government. I was put on a return flight to Bangkok, just two hours after I had landed, and found myself at the centre of a media storm and diplomatic row. The Global Times, a mouthpiece for the Chinese Communist Party, argued that any country has a right to refuse entry to anyone who poses a “serious threat to the security, stability and interests of the nation” – correct in principle, but hardly a category I had ever imagined belonging to.

My experience helped shine a spotlight on the erosion of Hong Kong’s freedoms and autonomy, and on Xi Jinping’s intense repression of any and all dissent. Yet that campaign of repression takes far more serious forms for Chinese activists, in Hong Kong and the mainland, than anything I experienced. I suffered an unpleasant inconvenience, but within 24 hours I was safely home in London, able to see family and friends, and free to speak out. Those in Hong Kong and mainland China who challenge the Communist Party face a far graver fate.

In Hong Kong, in recent years, booksellers publishing exposes of Chinese leaders’ private lives or critiques of the regime have been abducted.

Pro-democracy elected legislators disqualified.

Student leaders of pro-democracy demonstrations have been jailed.

In mainland China, human rights lawyers, bloggers, religious leaders and dissidents are jailed or disappear – and are subjected to the most horrific forms of torture imaginable.

The scale of China’s brutality has been revealed in a new and unique 40-page report published last month. Unique not so much for what it documents – major international human rights organisations have been reporting China’s abuses for years. But unique in terms of who it is authored by. For the first time ever, a human rights commentary has been smuggled out of China by a human rights lawyer who is still living in China – and, furthermore, has now disappeared.

Gao Zhisheng is perhaps China’s best known human rights lawyer, and certainly one of its bravest. Known for defending Christians, Falun Gong practitioners and other vulnerable groups, Gao’s licence was revoked and his law firm closed down in 2006. He was then sentenced to three years in jail but given a five-year suspended sentence on probation, charged with incitement to subvert state power. During his probation period he was forcibly ‘disappeared’ at least six times. On one occasion he was held incommunicado and tortured for six weeks. He was then returned to prison for a further three years.

On 7 August 2014 Gao was released from prison, but in August this year he disappeared again. Somehow despite the Chinese state’s authoritarianism, he was able to compile an analysis of the regime’s human rights violations, drawing on information provided by what he calls “a petitioner in dark nights”. He covers a wide range of themes, from violations of freedom of expression and religious persecution to land rights and police brutality, and describes China as a “killing field”. China, under Xi Jinping is, he says, enduring “the harshest and most brutal political oppression since the end of Mao Zedong’s rule”.

Gao’s analysis could be criticised for hyperbole. People in North Korea or ISIS-controlled territory in Syria or Iraq, for example, may take issue with his suggestion that “the cruel reality of extreme hostility to human rights has made documenting human rights in China the most dangerous cause in the world”. Unfortunately too many places in the world could lay claim to that description. But allowances should be made for the polemical style. This is an analysis written by a man who has suffered intense physical and mental torture, separation from his family, constant surveillance and repeated arrests or disappearances, and yet still had the extraordinary courage not only to write such a comprehensive document but to find a way to get it out of the country. It deserves to be read and taken seriously.

Gao provides numerous shocking, graphic examples of police brutality:

- The wife of a church pastor buried alive by a bulldozer destroying the church building;

- The shooting of a petitioner by a police officer;

- The torture of human rights defenders;

- A pastor, Bao Guohua, has been jailed for fourteen years, and his wife for twelve years, for protesting at the destruction of church crosses in Zhejiang;

- When a political prisoner, Peng Ming, died in jail, his brain, heart and other organs were removed – to cover up the cause of death or, in the regime’s account, for “medical research”;

- One activist, Huang Yan, suffered two miscarriages as a result of being beaten up by police and she claimed that one officer “kneeled on my body, grabbed my hair and pounded my head on the ground until it was covered with blood”. Her husband was seized, forced to kneel down under the hot sun, and told to divorce her because she is “a dangerous person”. Denied medical treatment for cancer, she was then unable to walk as a result of torture. “They took all my dignity away,” she added. “The torture was indescribable. They put seven sets of chains on my hands and feet, and sent in male inmates to beat me.”

Another account, by a former party official Wang Qiuping, describes how “they beat up, tortured, abused, disable and deliberately harmed the bodies of people… Handcuffs, chains, helmets, masks, bullet-proof jackets, hanging and beating, pinching testicles with clips” and used other torture to extract confessions. He was knocked unconscious three times in 313 days. “To extract a confession, they wouldn’t let me sleep for 120 days”.

The case against China isn’t just anecdotal:

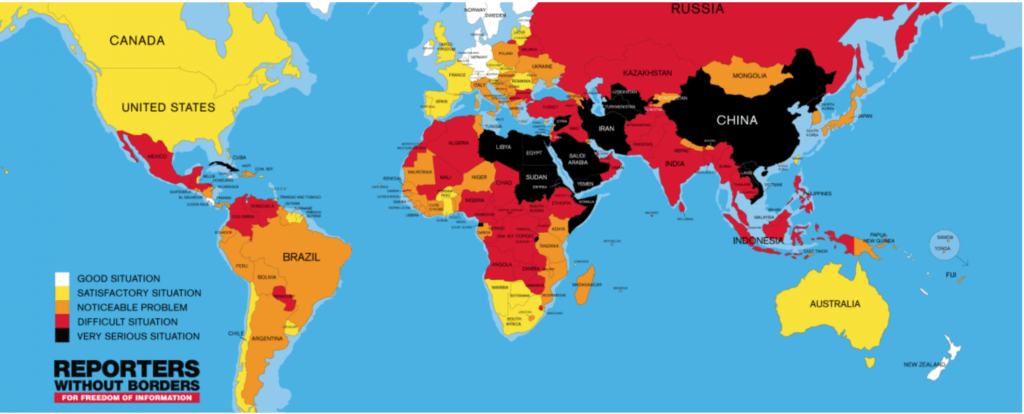

- China is ranked 176th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ index of press freedom.

- It is rated “the worst abuser of internet freedom” in the world by Freedom House[1. Freedom House reports: “China was the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom in the 2016 Freedom on the Net survey for the second consecutive year. Harsh punishments for expression and a deteriorating legal environment are significantly undermining civil society activism on the internet.” And the repression appears to be working: “Against the backdrop of stricter internet control across all platforms, digital activism has been gradually waning. While some individuals are still outspoken, observers noted a decline in the lively discussion of social causes which used to characterize popular microblogs.”].

- And the Committee to Protect Journalists records that it is the world’s second most active jailer of reporters[2. Turkey put most journalists (81) behind bars in the latest year – according to the New York-based Cttee to Protect Journalists – but China was in second place, with Egypt third.].

Gao describes how his own relatives have been hounded, their identity cards revoked. “The brutal persecution of my in-laws is just a snapshot of the … severe abuse of human dignity and basic human rights,” he says. Yet despite everything he has personally experienced, Gao himself is astonished at the scale of the brutality of Xi Jinping’s regime:

“I still can’t help but wonder when I’m documenting these human rights violations: can this be true? In today’s world and at this stage of human civilization, such a brutal and ruthless regime still exists – in China, in the 21st century.”

And he holds the international community complicit for its silence:

“The Communist Party of China has successfully terrorised and deterred the whole world with the enormous economic interests generated by the blood, sweat and labour of the poor people in China. The whole world has learned to be deaf and mute to [the] ruthless suppression of the Chinese people’s basic human rights, in exchange for the bloodstained economic interests … They allow economic interests to dictate their choices and the butchers get what they desire.”

The regime’s “dream world” is, he argues, one in which all dissent is silenced – but such a world, he adds, is “a dead world”. The regime wants a world “in which people are unanimous on everything”, because “the slightest difference looks very obvious and unpleasant to the controlling government”. But this “impulse to suppress or even eradicate such differences generates more conflicts”.

Gao’s work is a challenge to us all. It deserves to be read in the corridors of power. He has acted with extraordinary courage and is paying a very high price for his conscience. It is time for the rest of the world to rediscover its conscience, stand up to China and, at a minimum, demand Gao’s release.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe