Credit: Getty

In America, almost 100 people are dying from opioids every day.

Some experts predict that half a million more people will die over the next decade . Others think it will be closer to 650,000[1. Max Blau, ‘STAT forecast: Opioids could kill nearly 500,000 Americans in the next decade’, STAT, 27 June 2017] – the population of Miami, or Atlanta, or Sacramento. President Trump has rightly declared the crisis a “public health emergency”.

Last week Trump’s commission on ‘Combatting Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis’ published its recommendations. The report has had a lukewarm reception, not least as the question of funding remains unanswered. Yet much of what it does say – from cracking down on the illegal importation of opioids to expanding drug courts and removing barriers to treatment – is sensible (we’ll park the report’s proposal for a ‘just say no’ media campaign for now).

The problem with the report lies in what it doesn’t say. Because while it traces the role of big pharma in the development of the opioid epidemic, and it seeks greater oversight of prescribing, it fails to adequately link the two. In reality, the financial relationship between pharmaceutical companies and doctors is killing people.

Like big tobacco before, big pharma is being called to account

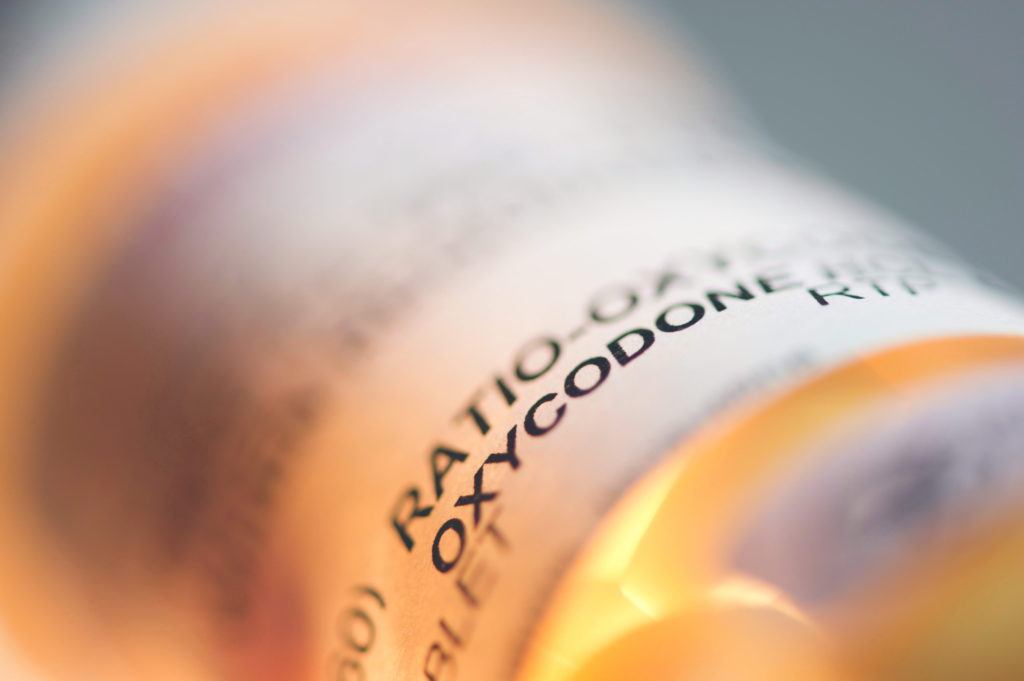

The opioid epidemic can be traced back to false advertising by big pharma in the 1990s, who peddled opioid-based painkillers as having lower risk of addiction than existing pain pills.[2. Barry Meier, ‘In Guilty Plea, OxyContin Maker to Pay $600 million’, The New York Times, 10 May 2007] More specifically, Purdue Pharma executives gave false information about their narcotic OxyContin, and doctors duly prescribed it – between 1996 and 2001 annual prescriptions increased almost 20-fold.[3. .‘Purdue Pharma, Execs to Pay $634.5 Million Fine in OxyContin Case’, CNBC, 5 August 2010] Over that period, OxyContin made Purdue Pharma almost $2.8 billion.[4. Barry Meier, ‘In Guilty Plea, OxyContin Maker to Pay $600 million’, The New York Times, 10 May 2007]

In 2007, Purdue Pharma finally agreed to pay $634.5 million in fines for those misleading claims, and three top executives pleaded guilty to criminal charges. 41 states are now suing the producers and distributors of opioid painkillers,[5. Yuki Noguchi, ‘41 States To Investigate Pharmaceutical Companies Over Opioids’, NPR, 19 September 2017] reminiscent of the mass litigation against tobacco companies. If these companies are also found to have made misleading claims, to have behaved negligently in doling out obscene volumes of highly-addictive pills (Vox reports that enough pills were prescribed in 2016 to almost fill a bottle for every US adult), massive settlements will follow.

But as the lawsuits snowball, there’s a danger we’re missing a longer-term opportunity to protect patients.

Financial incentives, even small ones, sway doctors

Three quarters of people whose heroin use began in the 2000s report they started with prescription drugs.[6. Theodore Cicero, The Changing Face of Heroin Use in the United States: A Retrospective Analysis of the Past 50 Years, JAMA, July 2014] Why are prescription drugs such a wide gateway? Because, the researchers find, “many users viewed these drugs as safer to use than other illicit substances”:

“prescription opioids are legal, are prescribed by a physician, and are thus considered trustworthy and predictable (eg, the dose is clearly specified on a distinctive tablet or pill)”.

In short, doctors – those we trust to help us when we’re at our most vulnerable – say prescription drugs are OK. How is a patient to know that, in fact, there is little evidence that opioid drugs are even effective at alleviating pain? Or that one in every 550 patients on opioid medication dies from an opioid-related cause – increasing to as many as one in just 32 for very high doses?[7. Thomas Frieden and Debra Houry, ‘Reducing the Risks of Relief — The CDC Opioid-Prescribing Guideline’, The New England Journal of Medicine, 27 April 2016] The information asymmetry between patient and doctor is vast, while our lives are quite literally in that health professional’s hands.

Which is why the Trump administration should be looking at the benefits, in cash and kind, that doctors receive from pharmaceutical companies aggressively pushing their drugs.

I’m talking about the culture of lunching, speech-giving, and honorariums (not legitimate research). Because research has found even a $20 lunch can influence a doctor’s prescribing habits – and the higher the value of benefits, the higher the rates at which the promoted drug is prescribed.[8. Colette De Jong, et al, ‘Pharmaceutical Industry–Sponsored Meals and Physician Prescribing Patterns for Medicare Beneficiaries’, JAMA Internal Medicine, August 2016] And it’s pervasive: analysis by ProPublica found that in 2014 three quarters of doctors across five common medical specialties received at least one payment (and they too found a correlation between payments and prescriptions).

For some doctors that’s being treated to a burger and fries by a local pharma rep, but for some it’s tens, even hundreds, of thousands of dollars in speaker fees, ‘consultancy’, exclusive dinners in high end restaurants, even golfing junkets. It may be illegal to pay doctors to prescribe a specific drug, but paying them to promote it is a different matter.

Research published in September looked at payments relating to opioid drugs specifically.[9. .‘Opioid makers made payment to one in 12 U.S. doctors’, Brown University, 9 August 2017] It found 375,000 opioid-related payments were made to more than 68,000 doctors in a 29-month period. That’s one in 12 physicians, and one in five family doctors, profiting (the average payment was $15, the median $50) from drugs at the centre of this public health emergency. And while the research is not proving cause and effect, the $46 million spent by pharmaceutical companies should be deep cause for concern.

No, all regulation isn’t bad, it protects consumers

Corporate abuse – in this case, the deliberate misbranding of opioid drugs – is a clear violation of regulatory, even criminal, standards (as shown in the Purdue Pharma case). But enforcing those standards, while vital, is not sufficient to protect patients. Nor is simply letting people look up in a database whether their doctor takes payments from drug companies. Patients have been able to do that through the Sunshine Act (part of the Affordable Care Act), but there’s no evidence of better behaviour.

There’s a read across to banking. In 2012 the then head of the UK Financial Services Authority Martin Wheatley gave a speech on the damaging effect of incentives in retail banking – his analogy works as well for health services:[10. Martin Wheatley, ‘The incentivisation of sales staff – are consumers getting a fair deal?’, FSA, 5 September 2012]

“This is not like when you go to a fast food restaurant and the server asks ‘do you want fries with that?’, or ‘do you want to go large?’. We all know they ask these questions because they are encouraged to make the most of every sale, and when customers are standing at the counter, they are more likely to say yes. But then we also know what to expect – chiefly lots of salt, calories and a bigger waistline. But far fewer of us actually have such a clear understanding of financial services. We also mostly trust those selling or giving advice to be acting in our best interests… The cost of going large may cost us a few pence – the cost of buying the wrong mortgage could see you lose your home.”

Regulators in banking understood that financial incentives skew staff behaviour, and that even if consumers know incentives are being used, the imbalance of knowledge makes further action necessary. They acted and banks changed their behaviour.

The takeaway for the health sector is that transparency is not enough.

Opioid prescriptions have been falling since their 2010 peak, but as the projection of half a million deaths over the next decade shows, it’s not enough to slow the path of destruction. And heroin-related deaths have more than quadrupled since 2010 – a cheaper, more easily accessible opioid for patients who have already become addicts.

The President’s commission’s plans for enforcement, education and treatment will hopefully help. But without addressing the cosy culture between pharma and physicians, greased by millions of dollars in payments and hospitality, patients are going to continue to lose out. That’s about preventing the next scandal.